STARTING YOUR LARVAL BATCH

Hatching and stocking larvae Captive broodstocks are not normally maintained in tropical zones where a ready supply of berried females is available from the wild or from grow-out farms, even though there may be advantages in doing so, as discussed earlier in this manual. Whether the berried females are obtained from a captive broodstock or from the wild, you should hold them in slightly brackishwater (~5 ppt) at 25-30°C and preferably at pH 7.0-7.2 until the eggs hatch. Slight salinity results in better egg hatchability and recent research (Law, Wong and Abol-Munafi 2001) indicates that careful control of pH markedly enhances the hatching rate (hatchability).

Temperatures below 25°C promote fungal growth on the eggs. Temperatures below the optimum also cause some eggs to drop and increase the time for egg development.

Temperatures above 30°C encourage the development of protozoa and other undesirable micro-organisms. Light does not seem to affect egg hatchability, although direct sunlight should be avoided. There is no need for you to feed females when they are only being held for a few days simply for larval collection.

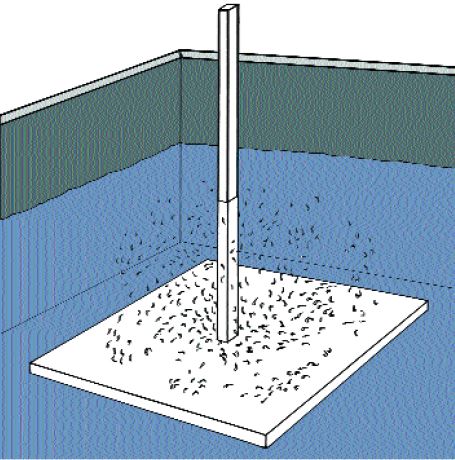

You can hatch your larvae in a special broodstock holding system (see Figure 12) and then transfer them to larval rearing tanks in 12 ppt water. In hatcheries operating recirculation systems, newly hatched larvae (Stage I) are often harvested from the broodstock holding tank using a collecting device. If you are operating a simple flow-through hatchery you can place females with brown to grey eggs directly into the larval tanks. Then, remove the females with a coarse dip-net after their eggs hatch. Some hatcheries put the females into coarse-meshed cages within the larval tanks, which makes them easier to remove after their eggs have hatched. When females are put into the larval rearing tank the water level should be about 30 cm and, as noted above, the salinity should be about 5 ppt with a pH of 7.0-7.2. After you have removed the females, raise the water level to the normal level (~70-90 cm) and adjust the salinity to the normal larval rearing level (12 ppt). Egg hatching, which occurs predominantly at night, can be observed by the presence of larvae in the tank and the absence of eggs on the underside of the abdomens of the females. Use a white board (Figure 33) to make it easier to observe larvae.

FIGURE33

Freshwater prawn larvae in tanks are difficult to see; using a white board will help

SOURCE: EMANUELA D’ANTONI

The rate at which you stock your larval tanks depends on whether you are going to rear them to metamorphosis in the same tank or if you intend to adjust the larval density by dilution or by transfer to other tank(s). Some hatcheries prefer to maintain their larvae in the same tank from stocking until the harvest of PL. The advantage of this is that the larvae are not subjected to handling. Handling brings with it the dangers of damage to the larvae and physical losses during the transfer operation. Other hatcheries prefer to stock the larvae much more densely at first and then to give them more space to grow by adding more water to the original tank (dilution rearing), or transferring all or some of the animals to other tanks later (two-stage rearing). The advantage of this alternative technique is that it reduces the quantity of water needed for the batch and permits more efficient feeding (the larvae are closer to the feed) during the early larval stages. A compromise between these two systems is possible. Three alternative stocking strategies are therefore suggested in Box 8.

You must select berried females that are all in the same stage of ripeness. This ensures that your larval tank will contain larvae of the same age (within 1-3 days) thus reducing cannibalism and making a proper feeding schedule applicable. You can obtain the initial stocking rates shown in Box 8 by estimating the number of larvae during transfer from the broodstock system (if you have one). Alternatively, if you are placing berried females directly into the larval rearing tanks, you can make some assumptions.

About 1 000 larvae are produced from each 1g of berried female weight. Berried females of 10-12 cm (rostrum to telson) normally carry about 10 000 - 30 000 eggs.

However, many eggs are lost through physical damage and cannibalism by the adult females during their transport from rearing ponds or capture fisheries, and some fail to hatch. Therefore, for example assuming that 50% of the original egg clutch is lost, five berried females of this size should be enough to provide a 1 m3 larval tank with about 50 larvae/L. It is important for you to check your actual stocking density and monitor the number of larvae you have during the rearing period, as discussed in the next subsection of the manual.

Counting larvae

Gross mortality during the larval rearing cycle is easily visible; counting the live animals is not necessary to see this. However, it is important for you to estimate the number of larvae you have in your tanks, both at the time of stocking and during the rearing period. This enables you to estimate survival rates, adjust the larval density, control your feeding schedule, and compare the performance of different batches.

You cannot count the number of larvae unless they are evenly distributed in the tank. Thoroughly mix the water in the tank by hand, and take at least 10 samples of a known volume of water (e.g. in 30 ml beakers, or glass pipettes with the ends cut off to give a wider diameter at the tip). Count the number of larvae in each sample. Multiply the average number of larvae/ml by the total volume of water (in ml) in the collection tank. Thus, for example, if the average number of larvae you see in a series of 30 ml beaker samples is 10, the estimated number you have in your tank is 10 ÷ 30 x 1 000 = 333 larvae/L. It is possible that automatic counting devices may be applied to freshwater prawn hatcheries in the future but few hatcheries are currently large enough to warrant the investment required.