1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Jellyfish

The word “jellyfish” is a popular term defining what marine biologists call gelatinous macrozooplankton.

The word “gelatinous” refers to the general consistency of these animals: their body is mostly made of extracellular matrix (often called mesoglea), i.e. the matrix that holds cells together and that is present in all animals, including us, but that, in these organisms, is the greatest portion of the whole body. Jelly refers just to gelatine. This body architecture is shared by animals that are very far from each other, in terms of evolutionary history. The fossil record tells us that true jellyfish are the oldest animals among those that are still living today, being represented in fossils that date back to the Pre-Cambrian. They are referred to the phylum Cnidaria (Cartwright et al., 2007). Vertebrates, including us, are referred to the phylum Chordata, and some chordates, namely the Tunicata, are also members of gelatinous macrozooplankton, with the Thaliacea and the Appendicularia. Gelatinous macrozooplankton, furthermore, comprises also the Ctenophora, or comb jellyfish.

The representatives of these three phyla are the bulk of gelatinous macrozooplankton and, together, make up what we call “jellyfish” (Boero et al., 2008). The following paragraphs contain a textbook-knowledge account of the three phyla, summarizing the information that is relevant for the scopes of this report.

1.1.1. Cnidaria

The true jellyfish are the planktonic stages of three cnidarian classes: the Hydrozoa, the Scyphozoa, and the Cubozoa. Most Scyphozoa and all Cubozoa fall within the category of macro- and even megazooplankton, since they are large enough, as adults, to be perceived by the naked eye, ranging from 2 mm (e.g. some small medusae) to 2 m in bell diameter, and several metres of tentacle length, of the largest medusae. Some Hydrozoa are macroplankters too, but many species belong to the mesozooplankton, being smaller than 2 mm. Gelatinous mesozooplankton is usually not perceived by a casual observer, unless when its representatives reach high densities.

Jellyfish move by jet propulsion, contracting their bells, or umbrellas. The umbrella usually carries tentacles on its margin and has a manubrium hanging in its cavity. The mouth is at the end of the manubrium. The tentacles catch the prey and bring it to the manubrium.

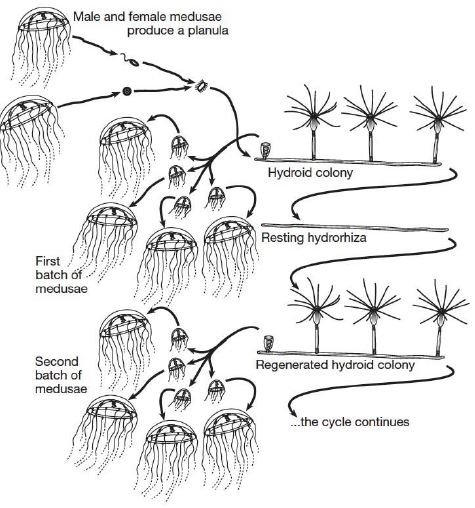

Cnidarians do have stinging cells, i.e. cells armed with cnidocysts, little capsules containing an inverted filament that can be everted to inject a venom into their victims (either preys or predators or... us). With very few exceptions, cnidarian jellyfish are carnivores, and use their cnidocysts to kill their prey that, according to the species, can be either other jellyfish, or crustaceans, or fish eggs and larvae, or anything reaching a viable size for the predator. Some, however, are microphagous or even contain zooxanthellae. Cnidarian jellyfish, also called medusae, have complex life cycles that often involve a benthic stage: the polyp. Jellyfish life histories often involve larval amplification. The adult medusae reproduce sexually, and each fertilization leads to the formation of a planula larva (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Life cycle of a pelago-benthic jellyfish (after Boero et al., 2008).

The larva settles and leads to a colony that can become quite large, feeding on other animals. A single colony, through asexual reproduction, can produce thousands of small medusae that, then, will grow to maturity. “Amplification” means that each fertilization event does not lead to a single adult but, instead, to many adults, due to asexual reproduction in the polyp stage. The sexually competent medusa is the adult, whereas the polyp stage, where the amplification occurs, is a larva. Hence: larval amplification.

Many Hydrozoan species have suppressed the medusa stage and are sexually mature as polyps. Whereas some Hydrozoans and Scyphozoans do not have a polyp stage, and spend their whole life as medusae. The Hydrozoa produce medusae by lateral budding, the Scyphozoa by strobilation, and the Cubozoa by complete metamorphosis of a polyp into a medusa.

Besides medusae, the Cnidaria can contribute to gelatinous macrozooplankton as floating or swimming colonies, such as the hydroids Velella and Porpita, or siphonophores like Physalia.

1.1.2. Ctenophora

Gelatinous macrozooplankton is usually equated to stinging jellyfish, and its presence causes major concern about own safety in non-marine biologists, due to fear of potential stings. Many members of gelatinous zooplankton, however, are not Cnidaria, and do not sting. The Ctenophores (Fig. 2) do not have a bell and a manubrium, and do not move by pulsations, they just share a gelatinous appearance with the Cnidaria. Ctenophores move by ciliary propulsion, through what zoologists call “ctenes” or combs. Hence the popular name: comb jellies. They can be a few centimetres, or even 50 or more centimetres, being globular, or similar to a dirigible, or ribbon like. Ribbon like ones, of the genus Cestum, can move also by snake like movements, but the other members of the group usually glide, appearing motionless and, in spite of that, moving. Their bodies are characterized by iridescent glows that are caused just by the flapping combs, the propulsors of the animal. Ctenophores have two tentacles armed with colloblasts, cell organelles that, instead of containing a venom, as the cnidocytes of Cnidaria, contain a glue that holds on

their victims. Like cnidarian jellyfish, they also feed on other gelatinous plankters, on crustaceans, or on fish eggs and larvae, being comparable to true jellyfish in their feeding habits.

Ctenophores have no impact on human health, and cannot cause any direct harm to us. Ctenophores are holoplanktonic (some are benthic, but will not be considered in the present account), there whole life cycle taking place in the water column.

Figure 2. A ctenophore: Leucothoea (art by A. Gennari).

1.1.3. Chordata

Pelagic tunicates (Fig. 3) are members of the phylum Chordata; they comprise the Thaliacea and the Larvacea, or appendicularians. The Larvacea are of small size, but can be present in very high quantities. The Thaliacea, namely salps, doliolids and pyrosomes, are of much larger size, pyrosome colonies and salp chains reaching several metres in length. Pelagic tunicates are much different from both Cnidaria and Ctenophora in their feeding habits, they are filter feeders upon protists (usually phytoplankton), bacteria and even viruses. Their life cycles are holoplanktonic and involve both sexual and asexual reproduction, with the possibility of high biomass increases due to formation of large colonies. Apparently, just as for Ctenophora, the pelagic tunicates do not have benthic stages.

Figure 3. A pelagic tunicate: Salpa (art by A. Gennari).