3. Importance of population structure in freshwater prawn farming

The characteristics of size distribution in freshwater prawns (Annex 8, Figure 1) has been mentioned many times in this manual. This section of the annex describes how various fac tors affect the size distribution of the prawns in your ponds.

THE EFFECT OF THE SEX RATIO

The proportion of females under grow-out conditions tends to be greater than males, pos sibly for the following reasons:

females may already outnumber males at stocking; and selective male mortality may occur in crowded pond populations.

Since the highest prices are generally obtainable for the largest animals, a prepon derance of females in a population may seem to be a disadvantage at first glance. It would appear to indicate that there would be a strong incentive to rear all-male populations of prawns. However, the effect of density on average weight is more extremely pronounced in all-male, compared to all-female populations. The use of all-male populations would there fore not remove the need to manage size variation and harvesting procedures very care fully. If maximizing the total weight of prawns produced per hectare is the main goal, the rearing of all-female populations at very high densities would be sensible. However, if max imizing the income from the pond is the main goal, proper management of mixed-sex or all male populations would be best, since the larger-sized prawns normally have the greatest unit value. Manual sexing has been done on an experimental scale but this requires extremely skilful workers and is very labour-intensive.

It is likely that commercial prepa rations of the sex-controlling androgenic hormone to sex-reverse the broodstock used to generate monosex populations will become available in future.

THE EFFECT OF DENSITY

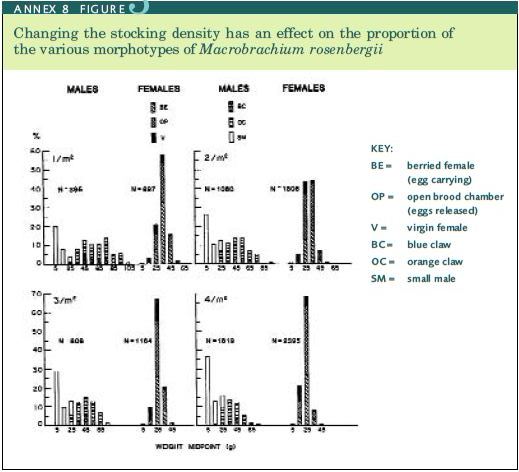

The proportions of the various male morphotypes change significantly with density (Annex 8, Figure 3). High density results in a larger proportion of SM. The frequency of the large BC males is highest at low densities. At high densities many prawns are in close contact with BC males, which inhibit their growth.

THE EFFECT OF UNEVEN MALE GROWTH RATE

Newly metamorphosed postlarvae are relatively even in size but size variation soon becomes noticeable. Individual prawns grow at different rates. This is known as heteroge neous individual growth (HIG). Some exceptionally fast-growing individuals (sometimes called ‘jumpers’) may become up to 15 times larger than the population mode within 60 days after metamorphosis, forming the leading tail of the population distribution curve. Jumpers became obvious within two weeks after metamorphosis. Slow-growing prawns (laggards) only become apparent later, about 5 weeks following metamorphosis. It has been suggested that growth suppression in laggards depends upon the presence of the larger jumpers. Male jumpers develop mainly into BC and OC males, while laggards develop mainly into small males.

ANNEX 8 FIGURE3

Changing the stocking density has an effect on the proportion of the various morphotypes of Macrobrachium rosenbergii

SOURCE: KARPLUS, HULATA, WOHLFARTH AND HALEVY (1986), REPRODUCED FROM NEW AND VALENTI (2000) WITH PERMISSION FROM BLACKWELL SCIENCE

Once this specific growth pattern has been established, juvenile prawns continue to show different growth patterns, even when they are isolated. Many studies have been con ducted on the effects (on harvest production and average animal weight) of grading prawns into different fractions depending on size but are outside the scope this manual to record. For further reading on this topic see the review by Karplus, Malecha and Sagi (2000). This research has provided important clues towards improved management of grow-out popu lations in freshwater prawn farming and form some of the background for the comments on grading in this manual.

THE SOCIAL CONTROL OF GROWTH

Social interactions between freshwater prawns are extremely important in regulating growth. In freshwater prawns the most important social interactions are the growth enhancement of OC males (what is known as the ‘leapfrog’ growth pattern) and the growth suppression of SM by BC males.

Growth enhancement of orange claw males

The change of OC males into BC males is sometimes called a metamorphosis because the differences between these morphotypes are so dramatic. An OC metamorphoses into a BC after it becomes larger than the largest BC in its vicinity (Annex 8, Figure 4). As a new BC male it then delays the transition of the next OC to the BC morphotype, causing it in turn to attain a larger size following its metamorphosis. The newly transformed BC is larger (sometimes much larger) than the largest BC previously present. This is known as the ‘leapfrog’ growth pattern, because the weight of one type of animal leaps over another.

BC males dominate OC males, regardless of their size, probably because of their larger claws. A prawn that has metamorphosed into a BC male and is larger than any other BC in its vicinity (following the ‘leapfrog’ growth pattern) becomes the most dominant prawn in the vicinity until it is overtaken by another prawn metamorphosing from OC to BC. The ‘leapfrog’ growth pattern results in the gradual descent in the social rank of exist ing BC males. When a new and larger BC appears on the scene, the ‘social ranking’ of all BC males present before that event fall.

Growth suppression of small males

The growth of runts (SM) is stunted by the presence of BC males. Food conversion effi ciency seems to be the major mechanism controlling this growth suppression in runts. Runts have poorer (higher FCR) feed efficiency when BC males are present. This seems to be governed by physical proximity; the phenomenon has not been demonstrated when these two types of prawns are separated, even when they are in the same water system and can see each other (i.e. chemoreception and sight are not factors).

As noted earlier in this annex, SM are sexually active. While they stay small they attract less aggression from dominant BC males (which are busier interacting with OC males) and are probably less vulnerable to cannibalism since they can shelter in small crevices. Being small and highly mobile, runts can find food on the bottom before being chased away by larger prawns, whether they be males or females. If BC males are removed from the population, some runts will increase their growth rate, and transform into OC males and, finally into BC males, following the normal ‘leapfrog’ growth pattern. This high lights the importance of regular cull-harvesting.