Seed availability for capture-based aquaculture eel

The life cycle of an eel may take 15-20 years to complete; despite reports that the life cycle of the European eel is expected to be closed soon (Anonymous 2003), artificial propagation of eels has not yet been achieved commercially. Knowledge of the availability of the species in the wild represents one of the hardest problems for fisheries managers (Shepherd and Bromage 1990).

This is primarily due to the fact that global eel culture is totally dependent on the availability of wild glass eels and elvers. The international eel market is supplied by Japanese and European glass eels? while other eel species form a minor part of the market. Glass eels are the “seed stock” of choice for Asian and European commercial eel farming, which relies on the combined glass eel fishery for all its “seed”. Anguilla anguilla in Europe produces 250-1 000 tonnes/year and A. japonica in Asia 100-150 tonnes/year.

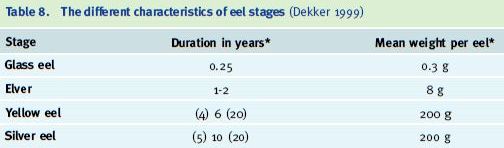

From the capture-based aquaculture point of view, it is the glass eel stages that are of most interest, while some elvers are produced for further on-growing by producers (Frost et al. 2000). The period of time the eels spend at each stage in their life cycle shows considerable variation (Table 8).

In all species, the females are larger than the males. Spawning age differs from males to females. For example, females of the American eel spawn at 8-12 years (500 g) whereas males spawn at 6-9 years (150 g) (Tibbetts 2001).

Table 8. The different characteristics of eel stages (Dekker 1999)

* figures in brackets are the shortest and the longest periods recorded

In Europe, the glass eel catch depends on the time that they ascend the rivers. European eels seem to be able to migrate up the rivers at lower temperatures (2-10°C) than Japanese eels. Early migrants are smaller in size (about 7 cm in length) than the later ones (15-20 cm). Glass eels used for farming are collected during the earlier migration, which can vary from autumn to winter. The best catches are generally obtained from February to May.

In Portugal, the first glass eels are caught during October, one month earlier than those in Spain (November and December). In Spain, the catch of glass eel declined from 60 tonnes in 1977 to 6 tonnes in 1997, while in Portugal the annual catch fell from 20 tonnes/year in the period 1976- 84 to 5 tonnes in 1997 (Ciccotti, Busilacchi and Cataudella 1999).

The fishing season in France is from November 15th to April 15th, with a special extension on the River Loire to April 20th. There may not be any significant catches until the end of December or the beginning of January. The start of the fishing season is very dependent on weather conditions and varies from year to year. The main catches are made from January to March. The main catching areas are in the Southwest of France, around Bordeaux. There is also a significant fishery in the Loire Valley, close to Nantes (www.glasseel.com). The total French glass eel catch has declined from 1 345 tonnes in 1970 to 578 tonnes in 1995 (Ciccotti, Busilacchi and Cataudella 1999).

In the UK, the principal catching season is from February to April, though some fish are caught as early as January and as late as June. There is no official closed season. The majority of the fishing takes place on the River Severn (www.glasseel.com). The UK Environmental Agency (UKEA 2000) confirms that all life stages of eels are exploited. Glass eel and elver fishing occurs in tidal reaches (the River Severn, the rivers of South-western England and South Wales). Yellow eels are exploited in many areas, although East Anglia is the main centre for this activity. Approximately 10 tonnes of elvers are caught each year while several hundred tonnes of yellow eels are caught.

Danish catches of glass eels are about 500 tonnes/year. The glass eels are used for restocking the commercial fishery, aquaculture (within Europe and for export), and direct consumption (Frost et al. 2000).

According to FAO data, the annual catch of the European eel decreased by over 40 percent from 1988 to 1998; only 7 546 tonnes of eels were harvested in 1998 (EIFAC/ICES 1999). The decline of this species is especially worrying since eels are important to many aquatic systems. They are particularly vulnerable due to their long and complex biological cycle, about which much is still unknown. In addition, as many as 25 000 people in rural Asia and Europe depend on the species for their livelihoods (Ringuet and Raymakers 2001). It has therefore become important to manage the European eel with the aim of restoring the stock and avoiding the possible decimation of the European industry. In January 2000, the EC Scientific, Technical and Economic Committee for Fisheries recommended “countries should be encouraged to stop the direct consumption of glass eels and to ban export of glass eels to countries outside the EU” in order to protect the eel stock (STECF 1999).

It has been suggested that changes in ocean currents might be affecting transatlantic migration of leptocephali, which then contribute to the decline in wild populations. The loss of available river habitats, land-based pollution, as well as alien parasitism, all advance the decline of the species. Also, dams are thought to contribute to the decline by limiting the migration of eels (in the “silver eel” stage) back to the sea, and possibly the subsequent reproduction and survival of early larvae; in addition, overfishing is a factor.

Trade plays a major role in the future of eel populations. Towards the end of the 1990s, Japanese eel populations collapsed as a result of the growing demand for the species in the Japanese food market. This contributed greatly to the demand for European glass eels in Asia, thus encouraging overfishing and poaching in Europe, with prices suddenly surging from US$ 88 to US$ 440/kg. In France, which was the first country in Europe to export live glass eels, it was estimated that as much as 80 percent of commercial glass eels came from illegal fishing in the mid-1990s.

At the same time (1988-98), the global aquaculture production of eels doubled from 98 000 tonnes to more than 200 000 tonnes, 95 percent of which was produced in Asian farms. As Europe has increasingly supplied the Asian eel farms with the necessary glass eels, Asia has gradually become more dependent on this form of capture fishery in Europe (Ringuet and Raymakers 2001). Young eels are mostly caught in Western Europe and then exported to eel farms in China, the Republic of Korea and Japan, and then sold and consumed mainly in Japan. From 1996, about 100-200 tonnes/year of European glass eels have gone to Taiwan Province of China, China and Japan (Ciccotti, Busilacchi and Cataudella 1999). In 1997, France exported more than 266 tonnes of European eels to destinations outside the EU (amounting to 55 percent of all EU eel exports outside Europe that year). This represents a vast amount of eels, since 1 tonne of European glass eels can contain as many as 2.5 million individuals. Eels from Western Europe are also used to restock both Central and Northern European rivers and farming facilities (www.traffic.org/dispatches/archives/ march2001/eel.html).

The Japanese eel occurs naturally only in the waters of China, the Republic of Korea, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Japan, and Taiwan Province of China. This form of capture-based aquaculture is totally dependent on natural sources. Therefore, the limited and very unpredictable supply of glass eels is a bottleneck in the further development of eel culture. In Japan itself, glass eels enter the rivers from October through to late May, when the water temperature is 8-10°C. Catches decreased from nearly 58 tonnes in 1990 to 20 tonnes in 1997, a decrease of 65 percent. However, a catch of about 38 tonnes was reported in 1998-99 (Frost et al. 2000).

In Taiwan Province of China, the glass eel catching season lasts from October to March (Pillay 1995) and yields between 30 and 150 million individuals, whereas the annual requirements of the local eel farms has been estimated at over 250 million glass eels. Significant increases in local catches are impossible, as the current level of glass eel exploitation in coastal Taiwan Province of China may already be about 45-75 percent of the natural population. The shortage must be made up by imports from the neighbouring countries of the Republic of Korea, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and China, which are the main suppliers of glass eels. However, due to the rapid development of a domestic eel culture industry in China, its exports of glass eels are now restricted, and the prospects for the eel culture industry in Taiwan Province of China are now poor (www.american.edu/projects/mandala/TED/eelfarm.htm). The exact level of the glass eel catch in China is not known. Frost et al. (2000) reported that 20 tonnes/year are caught domestically, while 120 tonnes are imported.

After the 1970s there has been a general decline in the availability of wild glass eels and elvers. Data collected between 1952-1992 showed that catches peaked in the 1970s and decreased until 1992, when most of the catch consisted only of the early pigmented stages (Lara 1994). Other authors showed that glass-eel production along the coasts of the Atlantic decreased from 1976 to 1984, probably as a result of increased catch per unit effort (Guerrault et al. 1986), while pollution seems to be the most important cause of the decrease in elver catches (Wondrak 1985).

Recruitment of the American eel (Anguilla rostrata) has also declined dramatically, in parallel to that of the European eel (A. anguilla). Since both species spawn in the Sargasso Sea and migrate as larvae to continental waters, this coincidence implies an Atlantic-wide cause, due perhaps to ocean climate. There is indirect evidence that the Gulf Stream weakened in the 1980s. A slower Gulf Stream could interfere with larval transport and generate observed patterns of declining abundance in the American eel and the European eel throughout Europe (Castonguay et al. 1994; EIFAC/ICES 2001).

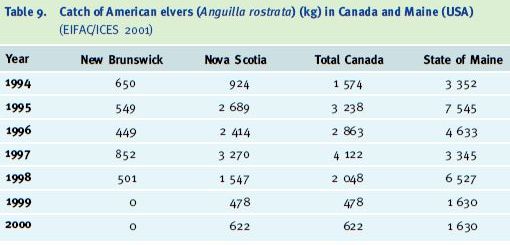

American eel elvers are harvested commercially in Canada, USA, the Caribbean and Central America. In Canada, the commercial fishery began in 1989 in the Scotia-Fundy area (EIFAC/ICES 2001), but catches declined from 4 122 kg in 1997 to 622 kg in 2000. The elver fishery is regulated in this area. The catch of American elvers in the Bay of Fundy, New Brunswick, the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia and in the State of Maine (EIFAC/ICES 2001) is shown in Table 9.

Yellow and silver eel catches have declined in the St. Lawrence and Ontario region. A series of major habitat modifications in St. Lawrence took place in the 1950 (St. Lawrence Seaway and hydroelectric dams), about 30 year before recruitment started declining; this long delay argues against these being the primary causes for the decline (Castonguay et al. 1994).

In the USA, an elver fishery existed in Maine during the late 1970s and collapsed until the 1990s, when Asian demand for elvers for aquaculture greatly increased. Dramatic declines in regional eel populations during the last decade and increasing harvest pressure on all life stages have prompted most north-eastern states to tighten the regulatory control of their fisheries. Minimum size limits of 4-6 inches (10-15 cm) and moratoria on elver collection are in effect until the current status of the eel stocks can be determined. In October 1996, a programme to compile stock assessment data and recommend a regional fishery management plan was initiated by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC); in November 1999 it approved the first Interstate Fishery Management Plan for the American eel (EIFAC/ICES 2001).

Table 9. Catch of American elvers (Anguilla rostrata) (kg) in Canada and Maine (USA) (EIFAC/ICES 2001)

Asian market demand for American elvers decreased in 1999, due to an increase in naturally available Japanese eel elvers, and the fact that the production of market-sized cultured eels exceeded Asian demand. The result was a reduced fishing effort throughout the area. Several other countries had developed elver fisheries in the 1990s, but no data is currently available (EIFAC/ICES 2001). About 1.25 million pounds (~ 567 000 kg) of eels and elvers were caught in the East Coast of the USA in 1995, the latest annual figures published by the ASMFC (www.ecoscope.com/eelnews.htm). Monitoring of elver catches began in 1998, both in the USA and Canada (EIFAC/ICES 2001).

The periodic reports by FAO of river eel captures in the Caribbean and Cantral America are believed to refer to glass eel/elver catches for export, which were about 49 tonnes/year recently. Incidental records (EIFAC/ICES 2001) refer to 0.4-7 tonnes of glass eels being caught in rivers in Holguin Province, Cuba. Potentially, FAO statistics for this fishery are underestimates; a better recording system for data is urgently needed.

Short-fin eels from the State of New South Wales, Australia have been exported to Europe and Asia for decades but the average annual commercial catch is only 100 tonnes; this is less than 1 percent of the world market for freshwater eels. Since there is a limited knowledge of eel stocks, and in an effort to avoid the problems encountered elsewhere, NSW Fisheries is taking a cautious approach to the harvesting of glass eels and the development of eel aquaculture in this State (Anonymous 1998a,b). Eel aquaculture relies on the availability and sustainability of its seed stock resource. Studies to date suggest a limited availability of glass eel resources in the State of Queensland, although their full extent may take many years to determine. To ensure the available resource is not over exploited, the Queensland Government manages the collection of glass eels, and does not permit their export; heavy penalties apply. Without such controls, the development of a sustainable industry would be severely impaired (www.dpi.qld.gov.au/fishweb/2691.html). Short-fin eels have a winter-spring arrival season in New Zealand, the main months being September-October (D. Jellyman, pers. comm., 2002).

Glass eel supply channels are very complex. In general, the international market is supplied by Japanese and European glass eels, but recently also by American eels at low levels. Worldwide, both legal sales and black markets for glass eels are thriving and there are conflicts between the catch data and market prices, and a general lack of any official data on this market sector, which for eels is the most important.

Japanese and Chinese fishermen catch Japanese glass eels in the waters around Japan. Fights occur between Chinese fishermen wishing to harvest these expensive glass eels, which they call “soft gold”. It has been reported that as many as 30 000 fishermen are operating 15 000 vessels to harvest glass eels; these have been obstructing shipping and “sometimes killing each other” in their efforts to harvest eels, which sell for as much as US$ 9 000/lb (over US$ 19 800/kg). The Yangtze River delta reports yields of up to 6 tonnes of glass eels per year (Anonymous 1996). China, being the main producer of eels, also has a big trade in the import and export of glass eels. China exports some glass eels to Taiwan Province of China (via Hong Kong) and Japan, but other producers use their entire catch domestically. Trading of cultured fingerlings occurs from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, the Republic of Korea and China to Japan, and from Japan to Taiwan Province of China, as well as within each country (Gousset 1992). Chinese statistical records indicate that some 110 000-125 000 kg of glass eels were imported in 2002, with about 70 000 kg via Shanghai and 50 000 kg via Hong Kong (www.glasseel.com).

The surging demand in Asia for fresh seafood and the loss of native eel stocks in Europe are driving a shadowy international market that pays US$ 1 000/kg for “legal” American glass eels air-freighted to Hong Kong, and up to US$ 5 000/kg for shipments of questionable legality (www.ecoscope.com/eelnews.htm). Asian glass eels have sold in Hong Kong for as much as

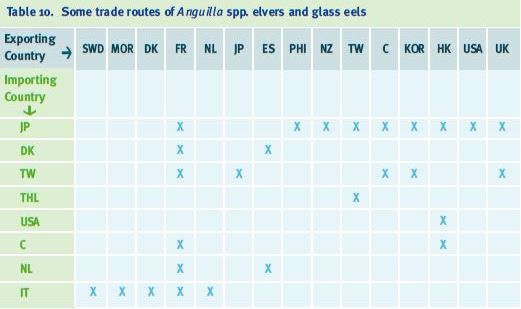

US$ 6 000/kg at times when US$ 1 000 would purchase the same amount of American elvers. It seems that some Hong Kong dealers mix their shipments with the cheaper American eels, and sell the combined batches to mainland Chinese fish farms at the higher price (www.ecoscope.com/ eelnews.htm). Table 10 is an attempt to show the trade routes of elvers of Anguilla spp. worldwide, but the overview is incomplete.

Table 10. Some trade routes of Anguilla spp. elvers and glass eels

Key: C = China; DK = Denmark; ES = Spain; FR = France; HK = Hong Kong; KOR = Korea (ROK or DPRK not specified ); IT = Italy; JP = Japan; MOR = Morocco; NL = The Netherlands; NZ = New Zealand; PHI = Philippines; SWD = Sweden; THL = Thailand; TW = Taiwan Province of China; UK = United Kingdom; USA = United States of America