Mortality rates from catching to stocking

As noted earlier, farmed bluefin tuna are mostly provided by purse seiners. The transfer of live fish from the seine to the towing cages is done in the open sea by swimming the fish from the purse seine into the towing cage (e.g.

90 m in circumference), generally where the catch has occurred. The transfer of the live fish captured with the purse seine system to the towing cages is affected by joining both nets, either by a “zipper system” or “sewing” them together. The tuna are then gently forced into the towing cage by lifting the purse seine. Several purse seine catches can be added to one towing cage before it is eventually towed to the grow-out area. Transfers from the catching area to the on-growing site can take from a few days to several weeks, depending on the position of the fishing area. In Mexico, towing distances can range from 90 to more than 800 km.

The transportation of adult specimens weighing hundreds of kilos to farming or fattening cages requires vessels capable of towing floating cages of great size at speeds not exceeding 1-1.5 knots, to avoid high bluefin tuna mortality rates due to the build up of lactic acid. Care must be taken not to crowd the fish, but rather to create a tunnel into which they can swim without any manipulation. These are manoeuvres difficult to execute, but the result is schools formed by specimens in perfect condition, which adapt rapidly to captivity. The low speed necessary for transport implies long return voyages that may take weeks, and it is also necessary to feed the fish en-route. This transport is usually done by very powerful tugboats that may cost in excess of US$ 2 500/day (Agius 2002). In Croatia fish are transhipped from purse seine fishing grounds to the farms by using a smaller cage (smaller specimens) towed by a boat - a distance up to several hundred miles if fish are captured within the Adriatic Sea or in other areas of the Mediterranean (Miyake et al. 2003). The counting of the fish trapped within the seine is usually done by divers, while cameras are used to count the fish when they pass from the seine to the towing cage. Average weight is preliminarily estimated from the dead fish in the seine.

In Australia, southern bluefin tuna schools are seined and transferred through a connection between nets to specialised Bridgestone cages/pontoons. As much as 100-130 tonnes of 15-25 kg southern bluefin tuna per pontoon are towed back at about 1.5 knots to the farm areas adjacent to Port Lincoln (South Australia), a process that may take several weeks and involves some feeding of the tunas. Mortality rates have averaged 4%, but in 2002 they decreased to ~2% (B. Jeffriess, pers. comm. 2002).

Mortality rates in the grow-out cages in Croatia were observed to be particularly high during the first month of adaptation (2.1%), decreasing significantly during the next months (0.6%). Stress related mortality in conjunction with injuries during seining and transporting procedures may cause high mortality rates. Compared to more advanced stages, smaller juveniles seem to be more stress sensitive (Katavic, Vicina and Franicevic 2003a,b).

In Japan, juveniles are caught in early spring by trolling in coastal waters. The newly-caught young fish react strongly to the stress of capture and confinement. The jaws or other parts of the bodies of these fish are sometimes injured (Munday et al. 2003). The skin is also delicate, and is damaged easily by mishandling, leading to high mortality rates at first (Nash 1995).

¦ Trends in aquaculture production

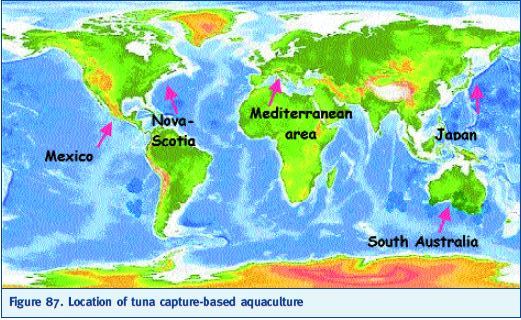

According to Ikeda (2003) the global supply of cultured tuna reached 20 000 tonnes in 2001. Bluefin tuna are cultured world-wide (Figure 87). Northern bluefin tuna are reared in the Mediterranean area (Croatia, Spain, Italy, Turkey, Morocco, Tunisia, Malta) and in Canada, Mexico, Japan and the USA; southern bluefin tuna are reared in Australia. Some of these activities are irregular or are at experimental levels. In general, tuna farming is expanding and license requests are increasing (France, Italy, Malta, etc.) and new countries are coming onto the scene, such as Greece and Libya (Agius 2002).

Figure 87. Location of tuna capture-based aquaculture

The supply of capture-based farmed tuna is mainly destined for Japanese “sashimi” but constitutes only 4% of the total amount of tuna required by the Japanese market. The supply of tuna (all the species) to the Japanese market ranged from 451 000 to 507 000 tonnes during the four years 1998-2001, but the ratio of fish with a high product value (“toro”) is decreasing (Ikeda 2003). “Toro” form only approximately 30% of the fishery catches but the capture-based farmed tuna are almost entirely considered as “toro”. “Toro” and other products are described in the marketing section of this chapter. The advantages of cultured tuna are its low price (a third or a half the price of captured tuna) and its easy availability in supermarkets, fresh fish shops or “kaiten-zushi” restaurants throughout the year (Ikeda 2003).

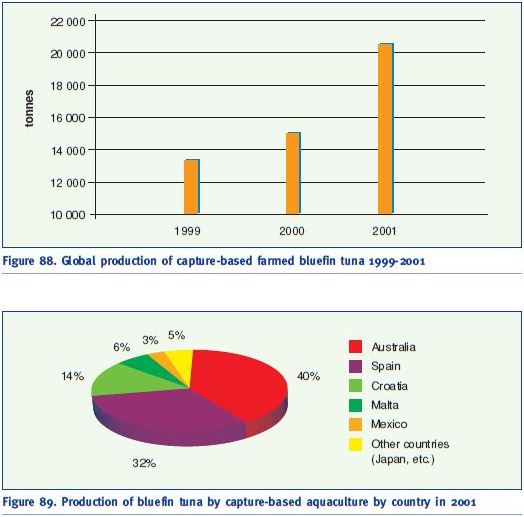

The trend in bluefin tuna capture-based aquaculture production from 1999 to 2001 is shown in Figure 88. The main capture-based aquaculture producers of tuna in 2001 were Australia, Spain, Croatia, Malta and Mexico (Figure 89). In these countries farms are often in joint venture with Japanese companies.

Figure 88. Global production of capture-based farmed bluefin tuna 1999-2001

Figure 89. Production of bluefin tuna by capture-based aquaculture by country in 2001