Marketing

Bluefin tuna are regarded as a high-grade product in Japan and are involved in an unusual marketing system, by seafood industry standards. Each fish is individually inspected for various quality attributes before being flown to Japan for the fresh tuna market. In the Tsukiji market (the Tokyo Central Wholesale market, which is also the largest wholesale auction market in the world for tuna), bluefin tuna prices are determined to a large extent by grade or attributes (Carroll, Anderson and Martinez-Garmendia 2001).

The weight of individual fish can affect pricing because of the economies of scale associated with transportation, and the consumer-ready product yield per size of whole fish. Their value is also a function of the relative quality of the individual fish (e.g. fat content) with respect to the available supply, the quantity of product available, and the concomitant presence of other types of tuna in the market.

The consumption of bluefin tuna depends strongly on the specific Japanese culture. Bluefin tuna is almost exclusively eaten raw in Japan. The four basic attributes on which fresh bluefin tuna traders rely to measure product quality are the freshness, fat content, colour and shape of the individual fish. Brokers in the United States and auction market officials in Japan grade these attributes from A-E (A representing the highest and E the lowest possible grade) to assist Japanese wholesale buyers in their purchasing (Carroll, Anderson and Martinez-Garmendia 2001). Traders are observing the gradual development of a niche market for “sashimi” in the United

States, and are using Japanese restaurants as a channel for distribution there. This is a result not only of the increasing popularity of raw fish among American consumers, but also of the recent weakening of the Japanese Yen relative to the US dollar (Carroll, Anderson and Martinez Garmendia 2001) and the economic crisis in Japan.

Farmed tuna are regarded as being in marketable condition after about 3-6 months of feeding. with the exception of those reared in Japan and Croatia, where fish are fattened for a longer time. The premiums achieved are generally based on freshness, high condition index and fat content (Smart, Sylvia and Belle 2003). The bluefin tuna is most appreciated by the Japanese consumer above all the other species, particularly the Mediterranean one. The price of bluefin tuna is double that of other “sashimi” tuna. The high demand is reflected in the price, which is generally the highest in the market, when compared to the other different tuna species.

The higher oil content in farmed tuna makes the product particularly suitable for “sushi”, since the oil is absorbed by the rice. Farmed tuna from the Mediterranean has a higher oil content than its Australian equivalent, and it is more appreciated in Japan; the oil also gives the flesh a more reddish colour, which makes it more attractive (Tudela 2002b). Different parts of the tuna command different prices; the most appreciated part is the external 6-10 cm (called “toro”), of which the ventral sections (denominated “chutoro” and “ootoro”) are the most valuable. The internal part (“akami”), is red and translucent. The bluefin tuna is the species which has the major quantity of high quality toro. Toro is graded by its fat content; in the past, the Japanese favoured leaner tuna, but in the last fifty years they have come to prize the tender, smoky taste of tuna with a higher lipid content. The word “toro” means “melt”, alluding to its “meltingly tender, buttery rich texture”. “Toro” is traditionally sliced thickly, inch or more for “sushi” and 1/2 inch for “sashimi”, to allow its rich flavour and soft texture to be fully appreciated. 1/4 Northern bluefin are known by the Japanese as “hon-maguro” (a general term for the northern bluefin), “kuro-maguro” (Thunnus thynnus thynnus) and “shibi-maguro” (Thunnus thynnus orientalis) and they are considered the best for “sushi”. Smaller “meji” (young bluefin tuna usually below 5 kg) are lighter and lack flavour, while the largest fish concentrate the distinctive tuna-flavoured oils. The deep red meat of “minami maguro” (Thunnus maccoyii) is richly flavoured but its quality varies considerably depending on the season (in the summer the fish reaches the highest fat content). Since both northern and southern bluefin reared in capture based aquaculture became available in reasonable quantities, they started to constitute a middle quality category in the market, filling the gap between the two extreme categories of quality. Farmed tuna are now sold even in Japanese supermarkets and are used in the popular and inexpensive “sushi” bars such as “rotating sushi bars” (Miyake et al. 2003).

The Japanese market trend controls the right moment for selling capture-based aquaculture tuna products. The aim is to sell when the total volume of tuna products is low; this is not so simple, as it is difficult to predict when bluefin tuna coming from the fisheries will arrive in the market. Sometimes it is so unpredictable that the result is a price decrease (Doumenge 1999). Strategies adopted by the farmers are different, and sometimes only fresh red tuna is offered, but achieves good prices; the harvesting of a few specimens must be repeated in an effort to try to select the best days for the market. This implies high freight costs (by air) and the necessity for specialised staff.

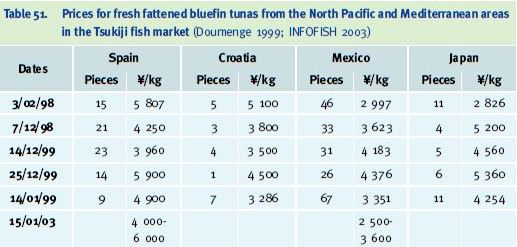

In 2001, Mediterranean capture-based tuna for the frozen market were selling at € 20/kg, ex farm. The prices for fresh fish are determined by auction prices in Japan, as well as airfreight charges. For the fish leaving Malta, the average prices are € 27-28/kg, because of the limited cargo space. For the fresh fish market, the fish are treated more or less individually and much more carefully. They have to be cooled down quickly, placed in boxes and then air-freighted (Agius 2002). Mediterranean and Californian capture-based aquaculture products are present on the Tsukiji market in significant quantities (Table 51). Spanish tuna arrive at the end of October, followed one month later by the Californian/Mexican production, and two months later by tuna from Croatia. The Spanish industry ceases to ship tuna in February, while the Croatian and Mexican farms continue to export. Australian production is concentrated between April and October. Prices for the Australian products are lower than for the northern bluefin (Thunnus thynnus), and competition is also stronger with other tuna species (such as Thunnus obesus) (Doumenge 1999).

Table 51. Prices for fresh fattened bluefin tunas from the North Pacific and Mediterranean areas in the Tsukiji fish market (Doumenge 1999; INFOFISH 2003)

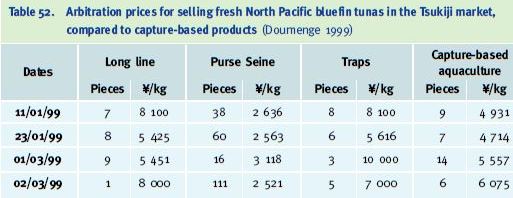

It is interesting to compare the prices of bluefin tunas from different types of fisheries with those from capture-based aquaculture (Table 52). Longline and trap products gain the best prices, while those from aquaculture are much more valuable than those caught by purse seine.

Table 52. Arbitration prices for selling fresh North Pacific bluefin tunas in the Tsukiji market, compared to capture-based products (Doumenge 1999)

The Japanese market for bluefin tuna is expanding and the Tsukiji market in Tokyo is no longer the exclusive market for “sushi” products, having been joined by the Nagoya, Osaka (Table 53), Sendai, Sapporo and Tokyo-Chuo (Table 54) markets. One 200 kg bluefin tuna recently sold at auction in Japan for a record US$ 390/lb (Magnuson, Safina and Sissenwine 2001), and a giant bluefin tuna (>500 kg) caught in the Canary Islands was sold (ex-ship Las Palmas) for US$ 44 500; the airfreight bill from Las Palmas to Tokyo was an additional US$ 21 000 for an individual fish (J. Dallimore, pers. comm. 2002). Prices fluctuate wildly (Figures 100 and 101), emphasising the importance of selecting the best selling date.

Table 53. Spot prices for fresh bluefin tuna in the Osaka market, 3 October 2002 (www.fis.com)

Table 54. Prices for fresh southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) in the Tokyo-Chuo market, 3 October 2002 (www.fis.com)

![Average prices of fresh bluefin tuna in the Osaka market, May-October 2002 [Note: Red = from Japan; Green = from Canada] Average prices of fresh bluefin tuna in the Osaka market, May-October 2002 [Note: Red = from Japan; Green = from Canada]](/images/aquaculture/capture021540164.jpg)

Figure 100. Average prices of fresh bluefin tuna in the Osaka market, May-October 2002 [Note: Red = from Japan; Green = from Canada]

![Average prices of fresh southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) in the Tokyo Chuo market, May-October 2002 [Note: Red = from Australia (wild caught); Green = from Australia (farmed)] Average prices of fresh southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) in the Tokyo Chuo market, May-October 2002 [Note: Red = from Australia (wild caught); Green = from Australia (farmed)]](/images/aquaculture/capture021540165.jpg)

Figure 101. Average prices of fresh southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) in the Tokyo Chuo market, May-October 2002 [Note: Red = from Australia (wild caught); Green = from Australia (farmed)]

The average price of fresh farmed southern bluefin tuna (Figure 101) is reasonably constant, while the price of the capture-based fish is more variable. This is mostly due to the guarantee of a good fat content for the fattened tuna. Extremes in the capture-based prices are often due to exceptional market conditions, or exceptional quality fish, which can command incredible prices.

The availability of imported frozen farmed tuna has increased, due to the explosion in capture based aquaculture. A new technology that allows freezing to -60°C in a shorter period of time (30-40% quicker than the “Japanese freezer boats”) is able to produce tuna that are of high quality, and can compete with fresh bluefin tuna on the market (FIS market report, 06/10/2002). Spain also exports some frozen farmed tuna to Japan, to be sold during February and March when the supply of fresh bluefin tuna is likely to be at its lowest (Miyake et al. 2003).

Although the Japanese economic crisis is still severe, the demand for both northern and southern bluefin tuna is always high. However, relying on a unique market (Japan) is becoming risky for capture-based aquaculture operators. The Yen devaluation in 2000 affected farmers’ incomes (20% below 1999) and investments. Despite the fact that value of tuna remains high, the prices Japanese consumers are willing to pay continue to decline, and the Japanese economy reached new lows in 2002. Japanese consumers are also starting to change their consuming habits, choosing less expensive products (de Monbrison and Guillaumie 2003). There is also competition with other tuna species (big eye, yellow-fin) which are less expensive (€ 3-6/kg cif Japan, compared to € 20-40/kg for bluefin tuna). Nowadays, the operators of capture-based aquaculture of bluefin tuna farms are trying to expand their market beyond that of “sushi-sashimi”, targeting consumers in other Asian countries, as well as the United States and Europe.

Conclusions

The capture-based aquaculture of tuna is expected to expand during the next few years, due to further technical developments and the market demand for its products. The long-term sustainability of the industry will depend on several factors:

? the reduction of baitfish utilization;

? the development of formulated feeds and reduced FCRs;

? improvements in feed formulation to ensure meat quality;

? the continued availability of “seed” material;

? the expansion of marketing activities away from reliance on Japanese markets; ? improved harvesting techniques; and

? improved offshore technologies for culture systems.

Environmental and ethical concerns (e.g. in the Mediterranean area) will continue to affect the functioning and image of the industry. Regulations are needed to create and control the traceability of products, as well as quality and environmental issues.

The prospect of achieving the captive breeding bluefin tuna, and being able to manage the complete life cycle, could represent a base from which the industry could further expand. This issue alone would remove ecological concerns and guarantee a sustainable future for the sector.