Availability of “seed” for capture-based aquaculture

Yellowtail aquaculture is still based, both in Asian countries and Mediterranean, on the availability of capture-based “seed”. This is the bottleneck for the capture-based aquaculture of Seriola spp., especially in Mediterranean countries, where the greater amberjack (S. dumerili) does not spawn in captivity. In Asian countries, mainly in Japan, artificial production of Seriola spp. “seed” has been achieved, but not at a commercial scale for sea-ranching and restocking goals.

This section of this report reviews the global trend and availability of yellowtail, their main catching areas and the management of the catches, e.g. in Japan for “mojako” (defined in the introduction to this chapter) of the Japanese amberjack (S. quinqueradiata), to prevent overfishing of the resource.

In Japan, S. dumerili has been reared from hatching to the juvenile stage (Masuma, Kanematu and Teruya 1990; Tachihara, Ebisu and Tukashima 1993); however, since 1988, most of the “seed” (8 to 10 cm size) has been imported from other Asian countries, mainly via Hong Kong from China and Taiwan Province of China (Wakabayashi 1996).

The natural spawning grounds of the adults of the Japanese amberjack (S. quinqueradiata), farmed mainly in Japan and in Korea, are in the East Chinese Sea, between Taiwan Province of China and Japan. The fish spawn in the warm waters of the Kuroshio current (18-20°C) as it moves northwards. Consequently, spawning begins north of Taiwan Province of China in the spring and finishes in the early summer off the southern islands of Kyushu and Shikoku (Kimura,

Kasai and Sugimoto 1994; Nash 1995; Kasai et al. 1998). The emergent larvae (about 3.5 mm) attach themselves to seaweeds drifting in the current. At first, they swim freely in the current as fingerlings up to 15 cm in length; afterwards they migrate in large numbers to the coastal waters of southern Japan and the Korean Peninsula.

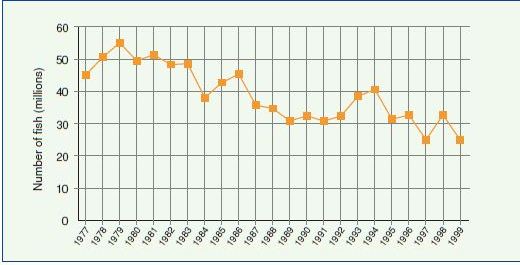

From season to season, various sizes of Japanese amberjack can be caught in different parts of Japan; therefore, special names are given to them in the different regions. For the Japanese, Japanese amberjack are ascending fish (“shusse-uo”), meaning that their name changes according to its size. To make it even more confusing, these names also vary on a regional basis. In the Kanto region of Japan (around Tokyo) the 2.5-5 cm long fry are called “mojako”. Fingerling Japanese amberjack up to the length of 15 cm are called “wakashi”. When they grow larger, up to 40 cm, they are known as “inada”. From 40 cm to 65 cm they are called “warasa” (mainly in Tokyo). Adult Japanese amberjack are called “buri” throughout Japan. Recently, the domestic supply of “mojako” showed a significant decrease (Figure 118), and several million have once again been imported from Korea (e.g. 8 million in the 1980s) and Viet Nam (e.g. 450 000 yellowtail fry were exported to Japan by Viet Nam in 1995).

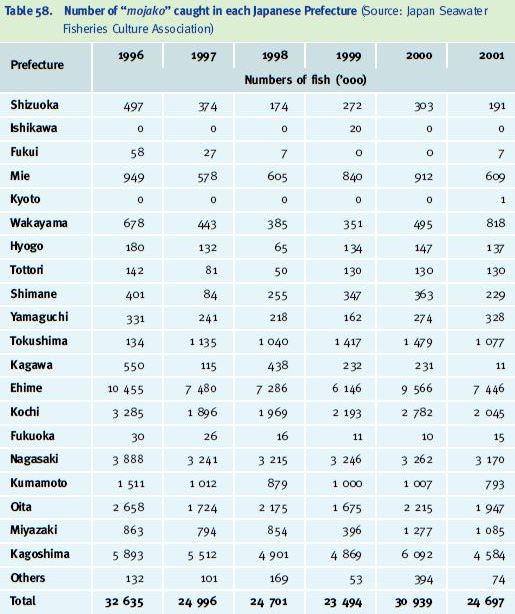

In 1966, the Japanese Fisheries Agency imposed regulations limiting the number of “mojako” that can be caught annually for aquaculture purposes to about 40 million, in order to protect the resource. Allocations are made to each prefecture by the Japan Seawater Fishery Culture Association. Each prefectural government decides on the allowable period for catching “mojako”, and allots the number of fish allowed to be caught to the individual Federation of Fisheries Cooperatives in the prefecture. In 1977, the number of “mojako” actually caught was about 45 million. The number has fluctuated wildly between 30 and 50 million for about 20 years but fell as low as 25 million in 1997 and 1999 (Table 58).

Figure 118. Fluctuation in the number of available “mojako” (Nakada 2000, modified)

Table 58. Number of “mojako” caught in each Japanese Prefecture (Source: Japan Seawater Fisheries Culture Association)

Yellowtail amberjack (S. lalandi; also known as yellowtail kingfish in Australia and goldstriped yellowtail in Japan,) are cultured commercially in South Australia and Japan, and experimentally in New Zealand. In Japan, this species is especially popular in the northern Kyushu area. In 1997, 2.5 million large juvenile yellowtail amberjack (“hiramasa”), were caught in the waters around the Goto Islands and cultured. The total annual catch of yellowtail amberjack is less than either Japanese amberjack or greater amberjack (Nakada 2000).

In the Mediterranean region (e.g. Spain), some experimental work has been undertaken. The production of greater amberjack S. dumerili is mainly based on raising fingerlings, captured from the wild at the end of the summer. The poor availability of wild juveniles and the high cost of catching them constitute a bottleneck to the commercial rearing of this species (Porrello et al. 1993). In general, the fishery area follows the geographical distribution of the species, with the greater catches being taken during the spawning season. The spawning season of S. dumerili is protracted and lasts from late spring to early summer (from May to July) (Lazzari and Barbera 1988, 1989a; Grau 1992) in the Mediterranean. Grau et al. (1996) found that the spawning season in the Balearic Islands occurs earlier than previously reported for the same species in other Mediterranean areas (Lazzari and Barbera 1988, 1989a). Lazzari and Barbera (1988, 1989b) and Andaloro, Potoschi and Porrello (1992) found that the main spawning site for the greater amberjack in the Mediterranean region is located in the Central Mediterranean Sea, off the Pelagie Islands.

The fishery for greater amberjack juveniles for aquaculture purposes is made in “nursery” areas located in Southern Adriatic (Benovic 1980), in Southern Sicily (Giovanardi et al. 1984; Lazzari and Barbera 1989a), in Eastern Sicily and in the Aeolian Archipelago (Greco et al. 1991, 1992; Porrello et al. 1993). Other recruitment areas were identified in the South Thyrrenian Sea by Caridi et al. (1992) and the juvenile availability was assessed by Andaloro (1993). For Italian fisheries, this species is considered an under exploited resource (Andaloro, Potoschi and Porrello 1992); the frequency of captures, the only available data for assessing biomass, shows a little change (Andaloro 1993). Catches of about 2 million juveniles/year (<200 g total body weight) were recorded on the northern and eastern coasts of Sicily, although most of them were caught by sport fishermen, and rarely for aquaculture purposes (Marino et al. 1995).