Fish health and disease

The rapid expansion of finfish aquaculture has resulted in many problems, particularly in the production of quality “seed”, the development of a suitable pelleted feed, the pollution of the culture areas and cultured fish diseases.

Disease and health issues have become very important and their diagnosis and treatment is a major issue for all fish farmers. Knowledge of diseases in cultured yellowtail is restricted to Japan and a few Southeast Asian countries, where mariculture is intensively practized. Many important groups of bacteria have been reported to cause disease outbreaks in farmed marine finfish, resulting in serious economic losses to the industry, vibriosis being the commonest (Leong 1992). According to Ogawa (2002), the lack of knowledge on diseases in many other countries in the region is mainly due to the lack of trained manpower. In Japan, Sano (1998) reported that the major diseases occurring in cultured species in 1993 could be categorized according to their causative agents: 37 bacterial, 17 parasitic, 11 viral, 4 fungal, 1 concurrent, and 9 others.

Fish intensively cultured in floating net-cages are often heavily infected with monoxenous parasites, particularly the monogeneans (Ogawa 2002), while fish extensively cultured in net enclosures or ponds generally harbour these parasites in low densities. The fry and fingerling of most species are highly susceptible to infections of protozoans, Cryptocaryon irritans and Trichodina spp., during the early stages of their introduction in floating net-cages. These infections represent the most serious risk to the industry owing to their high pathogenicity and resistance to conventional control methods. The management of farm diseases in Japan has caused a recent trend for increasing the size of cages and reducing stocking densities; these changes have resulted in a disease reduction and a health improvement.

The most important diseases of the Japanese amberjack (S. quinqueradiata) are Enterococcus seriolicida, Streptococcus, Pasteurella piscida (pseudotuberculosis), vibriosis, Nocardia and Flexibacter (Kusuda 1990; Nakada and Murai 1991; Egusa 1992; Kawakami et al. 1997) and a specific viral disease that affects fingerlings called “Yellowtail Ascite Virus” (YAV) (Ishiki, Kawai and Kusuda 1989). With production increasing, outbreaks of these diseases will probably also affect the greater amberjack (S. dumerili). The most serious problem in recent years has been the iridovirus infection, introduced from Southeast Asia, which has caused mass mortalities in yellowtail (Nakada 2000). A recent study reported an increasing number of disease problems in recent years (Yokoyama and Fukuda 2001); about 20 species of parasites have been found in cultured yellowtail. Of these, the myxozoans Ceratomyxa seriolae and C. buri were found in the gall bladder of cultured yellowtail.

As at March 1997, there were 25 approved drugs marketed in Japan for the treatment of bacterial diseases and used under the control of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Their use is limited and regulated by standard procedures. The Central Pharmaceutical Affairs Council is involved in licensing and evaluating drugs as to their safety, efficacy and residues prior to marketing aquatic products. Even after approval, drugs are used in aquaculture under the strict supervision of licensed veterinarians. No preventive measures or therapeutants are available to cope with viral infections. In 1997, a licence was given to manufacture an oral drug against lactococcosis occurring in cultured Japanese amberjack (Seriola quinqueradiata). Besides the use of vaccines or antimicrobial agents, available experience suggests that the addition of an “UGF” (unidentified growth factor) to fish feeds at a level of 2% has been found to support healthy growth while significantly inducing high non-specific hematocrit values (Sano 1998; Nakada 2000).

Vibriosis has caused severe losses in recent years among cultured yellowtail at some cage farms in the Republic of Korea. Among the bacteria isolated from the diseased yellowtail, Vibrio sp., found in the kidney was considered to be the causative organism. In August 1999 an outbreak of VSN (viral splenic necrosis) was reported in Hadong (Kyongnam province, Republic of South Korea) in Japanese amberjack (www.seafood.pknu.ac.kr/~fishpath/recent%20outbreak01.htm).

In the Mediterranean area, even where the on-growing of greater amberjack (S. dumerili) has shown good results in terms of excellent growth rates (Garcia-Gomez and Ortega-Ros 1993; Lazzari and Barbera 1989b; Boix, Fernandez and Macia 1993; Garcia, 1993a,b,c; Garcia, Moreno and Rosique 1993), their culture is compromised by several pathologies, mainly parasitic diseases. These have been reported on greater amberjack in Mediterranean countries by Crespo, Grau and Padros (1990, 1992), Genovese et al. (1992), Grau (1992), Grau and Crespo (1991), and Grau et al. (1993). Since larval rearing is not achieved in the Mediterranean area, on-growing is directly dependent on the capture of wild juveniles from the sea; thus the introduction of parasitic diseases from the wild into the culture facilities is hard to avoid (Grau et al. 1999). In the Balearic Sea, a total of 15 parasites have been found, belonging to Myxozoa, Monogenea, Trematoda, Nematoda, Copepoda and Isopoda. The most important were Myxobolus buri and the gill fluke Heteraxine heterocerca, typical of yellowtail and responsible for the most severe diseases (Paperna 1995). Other pathogenic species are Paradeontacylix spp., which were responsible for mass mortalities of cultured greater amberjack of the O+ class (Grau et al. 1999). Recurrent occurrences of mass mortalities have been occurring in the O+ age class since 1988, due to epitheliocystis and sanguinicoliasis (December to March) and pseudotuberculosis (October to January). Icthyophoniasis, vibriosis, trichodiniasis and equinostomatidiasis have also been reported in S. dumerili (Genovese et al. 1992; Grau 1992).

In Japan, where “seeds” of the greater amberjack are mainly imported from Asian countries (Wakabayashi 1996), many exotic micro-organisms and parasites have been found, probably introduced together with the fish eggs and larvae imported for aquaculture. In Japan the monogenean Neobenedenia girellae causes mortalities due to heavy infection; the unregulated importation of greater amberjack fry (S. dumerili) to Japan appears to have been the source of this parasitic infection since 1991 (Ogawa et al. 1995). A sudden outbreak of a disease caused by the trematode blood fluke Paradeontacylix occurred in May 1993 among net-cage cultured greater amberjack that had been imported from Haisa, China, a few months before the onset of the disease (Ogawa and Fukudome 1994). The main diseases reported in S. dumerili in Japan are epitheliocystis (Crespo, Grau and Padros 1990) and parasitic infections like microsporidiasis and Benedenia seriolae. B. seriolae is strongly host specific to Seriola spp. (Yoshinaga et al. 2002). Problems have also been found when rearing yellowtail and related species in warm waters, due to muscle parasites and ciguatera. Table 70 shows a synthesis of the principal pathogens of cultured yellowtail.

Both yellowtail amberjack and greater amberjack, especially those weighing over 5 kg, are sometimes known to ingest dinoflagellates which can cause ciguatera poisoning; however, when raised in cages and fed formulated feeds, they may not accumulate the poison. It is important to make sure that cultured fish will not contain ciguatera-toxin (Nakada 2000).

In the waters south of Kagoshima, aquaculture of these species is impossible because of “kudoa” parasitism in the muscles and internal organs. In some cases, cultured juvenile Japanese amberjack and greater amberjack have been killed by an iridovirus infection, which was originally introduced with wild juveniles imported from tropical areas. Cultured fishes are more vulnerable to diseases than wild fish because they are always under a degree of stress.

Table 70. Specific pathogens of cultured yellowtails

VIRUSES

Iridovirus

? Yellowtail Ascite Virus (YAV)

? Viral Splenic Necrosis (VSN)

BACTERIA

? Enterococcus seriolicida

? Streptococcus sp.

? Pasteurella piscida (pseudotuberculosis)

? Vibrio sp.

? Flexibacter sp.

? Nocardia kampachi

? Nocardia sp.

PARASITES

Protozoa

? Cryptocaryon irritans

? Trichodina sp.

Myxozoa

? Ceratomyxa seriolae

? C. buri

? Myxobolus buri

Monogenea

? Benedenia seriolae

? Neobenedenia girellae

? Heteraxine heterocerca

Trematoda

? Paradeontacylix spp.

Nematoda

Copepoda

Isopoda

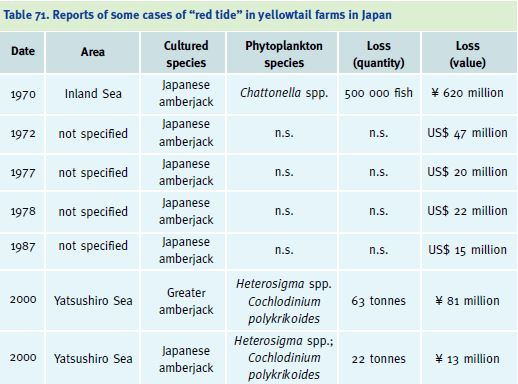

Another severe problem is related to the presence of toxic algal blooms, which can affect marine fish farming. Oxygen depletion may occur under cages, due to decomposition of accumulated waste materials. During the autumn, the oxygen-depleted layer may rise due to convection and cause oxygen depletion and associated mortalities in cages. Eutrophication in culture areas can also lead to the development of “red tide” phytoplankton blooms, which have also caused severe mortalities (Nakada 2000). In 1957, large-scale red tides began to be reported in the Seto Inland Sea of Japan. Since 1964, these red tides, due to harmful marine phytoplankton, have spread throughout the Inland Sea of Japan. In the summer of 1970, a red tide of Chattonella antiqua caused the death of 500 000 yellowtail, valued at ? 620 million (Table 71). Yellowtail aquaculture in the Seto Inland Sea has continued to suffer from the outbreaks of red tide of

Chattonella spp. In studies on the effect of Chattonella on the gills of Japanese amberjack it was found that fish dying from Chattonella exposure showed many types of gill lesions, while those of fish dying from environmental hypoxia showed very few lesions, thus demonstrating that the branchial oedema was caused by Chattonella and not by hypoxemia. This emphasises that, along with the promotion of aquaculture, the establishment of monitoring systems for red tides, and efforts to remove its causes, are urgently needed (Ono et al. 1998; Hishida, Ishimatsu and Oda 1999; Fogg 2002).

Table 71. Reports of some cases of “red tide” in yellowtail farms in Japan