Fisheries management

Within the fisheries management process (FAO 1997d), resources management requires considerable information on the biological characteristics, life-cycles, recruitment dynamics, habitat requirements, and fishery interactions for each exploited species. Marine fisheries management should ensure not only that wild populations of these fish are sustained at commercially viable levels, but also that market demands and the economic needs of fishermen are met, while harvest levels are adapted to cope with changing resources abundance.

Unfortunately, when little information is available about the status of a stock and its associated fisheries, potential problems tend to be ignored. As a result, most fisheries, both in developing and developed countries, are thought to be either heavily exploited or over-exploited. Many stocks have now been reduced to 10-30% of their original biomass (FAO 2000; ICLARM 1999a,b; Williams 1996).

Some management methods for fish stock assessments are based on catch-at-age data (Coleman et al. 1999). The data is used in Virtual Population Analysis (VPA) to reconstruct cohort-specific stock abundance and fishing mortality rates on the basis of past catches. The outcome of the VPA is then used to make annual recommendations for the Total Allowable Catch (TAC). The greatest problem with VPA is that it provides only hindsight information on cohorts that have passed through the fishery, but none on the cohorts that need managing (Coleman et al. 1999). Incorrect estimates would not reflect the real condition of the stock, and could lead to management actions that have a negative effect on both the species and the fishing industry. Recruitment forecasting allows management to anticipate problems and to take preventive measures to relieve fishing pressure (Koenig and Coleman 1998).

The cross-disciplinary nature of fisheries management with clear ecological, economic and social dimensions is likely to make solution finding a continuing topic of debate in the coming years. The economic and social aspects of fisheries management can in fact have a severe impact on the choice of management regime and the rigour with which it is imposed (Hall 1999). The conventional management methods used at national and regional level include the following (Jennings, Kaiser and Reynolds 2001):

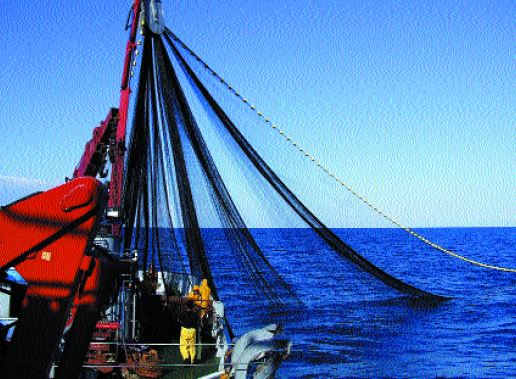

? Catch controls: these are intended to control fishing mortality by limiting the weight of catch that fishers can take. They include total allowable catch (TAC) or quotas (Q) which are limits on the total catch to be taken from a specified stock (Figure 143), as well as individual quotas (IQ) and vessel catch limits where the TAC is divided between fishing units. Catch controls are amongst the most widely used management regulation. IQs restrict the catches of individual fishers or boats. The sum of all IQs will equal the TAC. If IQs can be bought and sold by fishers than they are known as individual transferable quotas (ITQ). TACs are set to meet the target levels of fishing mortality determined by stock assessment. They may be fixed, or they may change from year to year because fish stock fluctuates and the future is unpredictable. In order to adjust catches from year to year, the government or regulatory authority may buy and sell ITQs.

? Effort controls: these limit the number of boat or fishers who work in a fishery, the amount, size and type of gear they use, and the time that the gear can be left in the water. Effort controls may also limit the size or power of vessels and the periods when they fish. The aim of effort control is to reduce the catching power of fishers and thus reduce fishing mortality. Effort control can be divided into licences, individual effort quotas (IEQ) and vessel or gear restriction. Limited licences restrict the number of boats or fishers in the fishery. Licences can be transferable. Effort quotas limit the amount of time spent working by a given unit of gear, a vessel, or a fisher. An individual transferable effort quota is a tradable IEQ. Vessel or gear restrictions try to limit the catching capacity of vessel or fishers. These may control the size and the design of pots or nets or the dimension of a fishing vessel, or may ban specific gears that are seen as too effective.

? Technical measures: these restrict the size and sex of fished species that are caught or landed, the gears used and the times when, or areas where, fishing is allowed. The size of individuals that are landed may be controlled by minimum landing sizes (MLS). Time and area closures can protect fished species at specific phases of their life history. Examples are the protection of juvenile nursery areas or adult spawning grounds. Time closures can protect annual stocks until their production and quality is high, but also lead to market gluts at the start of the fishing season. Time and area closures have been most effective when used in conjunction with other measures such as catch and effort controls.

Figure 143. Fishing bluefin tuna for capture-based aquaculture in the Mediterranean (an example of quota regulated fisheries) (Photo: F. Ottolenghi)