AQUACULTURE DEPENDENCY ON THE WILD STOCK

Reliance on wild seed

As mud crab hatchery development on a commercial scale has only occurred in a few countries, farms in most countries are dependent on wild caught stocks. It is only in countries such as China and Viet Nam, where there is significant expansion of the mud crab hatchery sector, that hatchery produced seed-stock will contribute a significant percentage of overall production in the near future.

In the Philippines it is estimated that 95 percent of crab seedstock is collected from the wild. In contrast in countries where collection of wild seed stock is banned under management plans e.g. Australia, the farming of crabs is totally dependent on hatchery produced stock.

Limits of seed supply

The loss of mangrove forests, over-exploitation of wild crab stocks and inadequate wild production to support increasing demand are the key factors that have driven the development of hatchery technology for mud crabs (Lindner, 2005). The supply of seed stock from the wild varies over time, as recruitment to the fishery is seasonal (Walton et al., 2006b), as reflected in the variation of zoeal abundance in near shore waters (Sara et al., 2006). As zoeal distribution and abundance is correlated with salinity, recruitment to different areas will also be affected by climatic variability (Sara et al., 2006). Heavy fishing pressure on mud crab fisheries in the Philippines has been reflected in decreasing relative abundance, mean size at capture, yield and catch per unit effort (CPUE) in two studies (Lebata et al., in press).

In some municipalities in the Philippines, the number of crablets being transported out of the municipality is being restricted because of fears of over-fishing. A number of research organizations are helping municipalities by assessing their stocks of crabs and providing support to policy and management plans.

Threats to mud crabs generally, which would also impact on seed supply, can include algal blooms, industrial and urban run-off, and their over-exploitation such as occurred in India in 1990 which led to their export being banned (Aldon and Dagoon, 1997). The supply of crab seed-stock can also be limited by the number of fishers targeting the species (Say and Ikhwanuddin, 1999).

In some countries up to 4 species of mud crab can be found. As a result, stocking with wild crab seed-stock can result in multiple-species being grown in the same grow out system. This creates problems as all species have different growth rates, and the faster growing species may well cannibalise the slower growing species, and generally complicate animal husbandry.

The need for a consistent, reliable year-round supply of mud crab seedstock to support farm expansion will underpin the future significance of mud crab hatcheries.

Economics of wild versus farmed seed

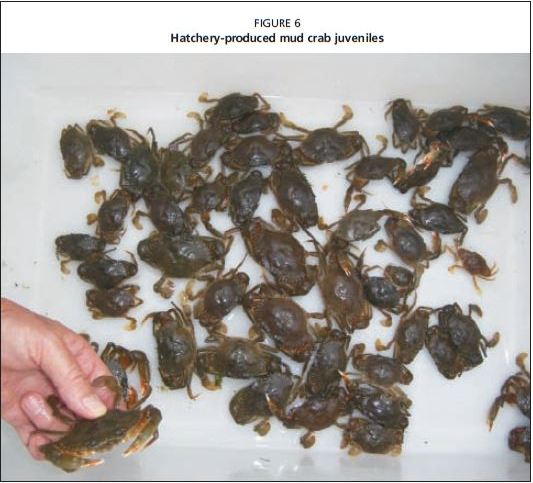

There are a number of reports on the economic performance of mud crab culture (Aldon, 1997; Baliao, De Los Santos and Franco, 1999a; Cann and Shelley, 1999; Say and Ikhwanuddin, 1999; Christensen, Macintosh and Phuong, 2004; Samonte and Agbayani, 1992a; 1992b; Trino, Millamena and Keenan, 1999a). Information regarding wild seed versus farmed seed appears anecdotal at best, with most trials using either wild or farmed seed, not both. As hatchery reared stock have only relatively recently become available in a few countries, most economic reports to date were based on grow-out of juvenile crabs collected from the wild (Figure 6).

It has been demonstrated that profitable crab farming operations can occur using wild seed-stock at various densities (Trino, Millamena and Keenan, 1999a), although the most profitable density is likely to be related to both the system and management of operations that can minimize cannibalism and improve the food conversion ratio (FCR). It has also been shown that farming mono-sex cultures of crabs may increase economic return, with one report reporting a return on investment of over 100 percent (Trino, Millamena and Keenan, 1999a).

The effects of harvesting regime on the profitability of mud crab farming in ponds was examined by Rodriguez, Trino and Minagawa (2003) who found that a bimonthly

FIGURE 6

Hatchery-produced mud crab juveniles

selective harvesting regime could improve profits compared to one terminal harvest. They argued that a selective harvesting regime increased overall survival to harvest as more space was available to those crabs left in the ponds and a more homogenous size range of crabs was maintained, as typically large crabs enter harvesting traps first.

The profitability of growing mud crabs in mangrove pens has also been documented (Trino and Rodriguez, 2001). They found a stocking density of 1.5 crabs/m-2 fed on a mixed diet of mussel flesh and fish bycatch to be most profitable, obtaining returns of 49–68 percent return on capital investment.

Dependence on wild caught feed

In a workshop examining the status of mud crab aquaculture, Allan and Fielder (2003b) summarized that “... diet development to reduce dependence on trash fish in Indonesia, the Philippines and Viet Nam, and to allow for grow-out in Australia, was the highest overall priority for mud crab aquaculture.” This reflects the current situation in most countries where mud crabs are farmed, where the principal source of feed is wild caught trash fish and molluscs.

A key challenge facing the rapidly growing mud crab farming sector in countries such as Viet Nam, Indonesia and the Philippines is the lack of a formulated aquaculture feed made especially for mud crabs (Allan and Fielder, 2003a). There are concerns that industry growth may ultimately be constrained by the dependence on low value trash fish and fishmeal popularly referred to as the “fishmeal trap” (Funge-Smith, Lindebo and Staples, 2005).

Whilst formulated mud crab feeds are now available in a number of countries where mud crabs are farmed e.g. China, Philippines and Viet Nam, there is scope to improve formulations and to reduce their cost.

Availability of wild feed

Wild caught feed resources

Crabs have a varied diet naturally and seem to grow well on a wide variety of feeds. In the Philippines typically chopped trash fish are used, but animal hide, entrails and snails (golden kuhol) have also been reported (Aldon, 1997), as has brown mussel flesh (Rodriguez, Trino and Minagawa, 2003). While research is underway to develop a specialized crab feed, trash fish resources in many regions are under severe pressure. This pressure is resulting in higher prices for trash fish and also conflict with human consumers of seafood, who themselves would like to consume so-called “trash fish”.