4.2.4 Induced spawning of oviparous bivalves

Other commercial species reared in hatcheries are known as oviparous as compared with the larviparous oysters discussed above. Oviparous species shed their eggs and/or sperm into the surrounding water where fertilization takes place.

Various stimuli can be applied to induce spawning; the most successful being those that are natural and minimize stress. The description that follows is of a technique known as thermal cycling, which is the most widely used method for oviparous species. As a general rule of thumb, if stock do not respond to thermal stimuli within a reasonable period of time, the gametes they carry are most likely not fully mature.

The use of serotonin and other chemical triggers to initiate spawning is rarely beneficial. Eggs liberated using such methods are often less viable than are those produced in response to thermal cycling.

4.2.4.1 Thermal cycling procedure

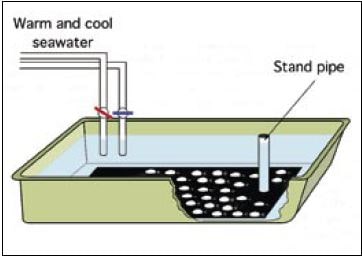

Mature bivalves taken from broodstock conditioning tanks are cleaned externally to remove any adhering debris and fouling organisms from their shells and then are thoroughly rinsed with filtered seawater. After cleaning they are placed in a spawning trough or tank. The preferred tank-type is a shallow, fibreglass tray of approximately 150 x 50 x 15 cm depth – 10 cm water depth (Figure 45).

It needs to be of a size that can be viewed by two or more operatives who are experienced in detecting the onset of spawning by adults (an important point in the spawning of monoecious species – see later).

Figure 45: Diagram of a tray arrangement widely used for the spawning of oviparous bivalves. (After Utting and Spencer, 1991)

The trough is often fitted with a standpipe drain and two filtered seawater supplies, one heated or chilled to 12 to 15oC and the other at 25 to 28oC (e.g. for Crassostrea species and Manila clams). Lower temperatures apply to cooler water species. The importance is the differential between the lower and higher temperature, which will normally be about 10oC.

The base of the trough is painted matt black or is covered by black plastic sheet to provide a dark background against which gametes being liberated can be readily seen (Figure 45).

The trough is part filled with the cooler water to a depth of about 10 cm and a small amount of cultured algae is added to stimulate the adults to open and start pumping activity. After 30 to 40 minutes the water is drained and replaced with water at the higher temperature, again with a small addition of algae. This water is drained after a similar time period and replaced with cooler water and the procedure is repeated.

The number of cool/warm cycles that are required to induce spawning depends on the state of maturity of the gametes and the readiness of the adults to spawn. In summer the adults may spawn within an hour of induction, but earlier in the season it may take 3 or 4 hours of cycling before the first animal spawns. Generally, if the adults do not respond within a 2 to 3-hour period they are returned to the conditioning tanks for a further week. Adults may start spawning on either the cool or warm part of the cycle, most commonly the warm. Although it is generally the case that males will spawn first, this cannot be guaranteed.

Additional stimuli can be provided in the form of stripped eggs, or sperm from an opened male. The gonad is located at the base of the foot in clams. In scallops it is a separate organ and can be seen when the mantle and gill tissues are lifted. If the gonad is carefully punctured with a Pasteur pipette and suction applied, quantities of gametes can be withdrawn which can then be mixed in a small volume of filtered seawater before adding to the seawater in the tray. In clams with discrete siphons, the diluted gametes are directed towards the inhalant siphon of active clams with a Pasteur pipette so that they are drawn into the mantle cavity by the pumping action of the adults. The inhalant siphon is the siphon furthest away from the hinge and has the largest diameter aperture. When spawning occurs in clams, gametes are expelled through the exhalent siphon as shown in Figure 38. The thermal shock during the second warm water cycle almost always elicits a spawning response in ripe clams and in other fully mature, oviparous bivalves within 1 to 2 hours.

4.2.4.2 Spawning dioecious bivalves

In dioecious species (refer to Table 9), in which the first adults to spawn are almost invariably males, it is good practice to remove them from the trough and leave them out of water until sufficient eggs have been collected from spawning females. The reason is that sperm ages more quickly than eggs and if more than 1-hour-old at the time fertilization is made, fertilization rate may be reduced.

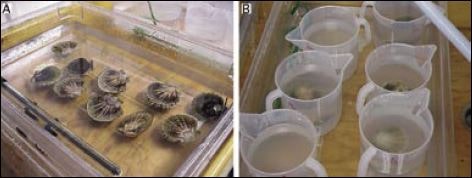

Figure 46: A – Pecten ziczac adults undergoing thermal cycling in a spawning tray. Note the aquarium heater used to maintain the elevated temperature. A similar tray of water is chilled with ice packs to provide the cold shock. B – Individual scallops spawning in 3 l plastic beakers immersed in a constant temperature water bath. While this species is not dioecious, the illustration applies to procedures used in spawning any species.

As each female begins to spawn it is necessary to remove it from the spawning trough and transfer it to an individual spawning dish or beaker part-filled with filtered seawater at 24-26oC (Figure 46). The dishes/beakers are contained in a heated water bath to maintain the temperature. The same procedure applies to spawning males, which can be identified as such by the continuous stream of milky fluid escaping from the exhalant siphon compared with the granular appearance or clumps of eggs shed by a female. Females may start spawning as much as 30 to 60 minutes after the first male begins to liberate sperm.

Time to completion of spawning for an individual is variable but gamete liberation rarely lasts for more than 40 to 60 minutes, often a shorter period in females. It may, however, be necessary to remove a spawning female from its container and place it in a fresh one when large numbers of eggs have been liberated. The presence of dense concentrations of eggs in the water inhibits pumping activity and hence the expulsion of further eggs. In addition, the female may start to filter the eggs out of suspension.

Eggs may be liberated in clumps that will eventually settle to the base of the dish or beaker. These clumps are separated when spawning is completed by carefully pouring the dish contents through a 90 ?m nylon mesh sieve (eggs will not be retained by this mesh size), retaining the separated eggs on a 20 to 40 ?m mesh sieve. The eggs are then gently washed into a clean glass or plastic container with filtered seawater at the required temperature. “Clumpy” eggs often do not fertilize well. The best success is most often obtained when females liberate streams of well-separated eggs that remain in suspension for longer periods than do the clumps.

When first spawned the eggs are pear-shaped but they rapidly hydrate and assume a spherical shape when in contact with seawater. Eggs from different females are collected separately to provide opportunity to visually assess quality using a microscope at about

Part 4 - Hatchery operation: broodstock conditioning, spawning and fertilization 77

x100 magnification. Batches of eggs that do not round off after about 15 to 20 minutes in seawater should be discarded. Reproductive development in the females of oviparous bivalves is not completely synchronous so that at any point in time eggs spawned by different females will be at slightly different stages of maturation. When separation and examination of the eggs is complete, batches of eggs that appear good can be pooled in a larger volume container.

Sperm from the various males that spawn are similarly pooled. It is good practice to use eggs from at least 6 females and sperm from a similar number of males to provide larvae for a production run. This ensures satisfactory genetic variability among the offspring, the extent of which will depend on the degree of heterozygosity of the parents. Small volumes of the pooled sperm suspension are mixed with eggs during gentle agitation of the contents of the container in the proportion 1 to 2 ml per l of egg suspension.

4.2.4.3 Spawning monoecious bivalves

The procedure to spawn hermaphroditic species, including many species of scallops, in which individual adults mature both eggs and sperm synchronously, is more complex. Here, the objective is to minimize chances of eggs being fertilized by sperm from the same individual (self-fertilization). It is rarely the case that an adult will spawn both eggs and sperm at the same time. More usually, sperm will be liberated first followed by the eggs. Individuals will often revert to liberating sperm once their eggs have been spawned.

There are two approaches to maximize chances of cross-fertilization. Large numbers of adults can be spawned in large-volume, deep tanks. These are fitted for flow-through so that the contribution of sperm from a particular individual is a small proportion of the total and the overall amount of sperm is continuously being diluted by water flow. When individuals switch to female production, the denser eggs are retained in the tank and chance dictates that the eggs of that individual will more likely be fertilized by the sperm of other individuals than by its own sperm. This method – applicable also to the large-scale spawning of dioecious species, where self-fertilization is not an issue – is used in mass production facilities for Argopecten purpuratus in Chile and is also used in the pond culture of bivalves in Asia.

Alternatively, permitting closer control of fertilization, each adult is transferred to a small container of filtered seawater at the required temperature once it begins to spawn (Figure 47). The container is labelled with the time and a reference number that will follow the progress of that particular adult throughout its spawning activities. As the adult spawns and clouds the water with its gametes, it is moved to a fresh, clean container after first being thoroughly rinsed with filtered water. This container is labelled with the time of transfer and the same adult-specific reference number. Careful observation is maintained on each beaker containing an adult liberating sperm in order to detect the onset of egg liberation, which is usually a sudden change. As each adult switches to egg production it is immediately removed and transferred to another container after rinsing, carrying with it the same adult-specific reference number and the time of the switch. Once sufficient eggs have been spawned, the adults are removed from the beakers before they revert back to sperm production. Thus, eggs and sperm are separately accumulated from each adult, identified as to origin by the different adult-specific reference numbers and time of production.

Mature adults with ripe gametes obtained directly from the sea can be induced to spawn in the hatchery in the same way.

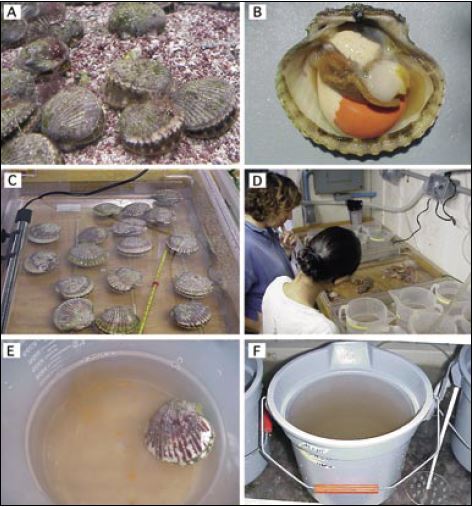

Figure 47: This sequence of photographs illustrates the spawning of the monoecious calico scallop, Argopecten gibbus, at the Bermuda Biological Station for Research, Inc. (BBSR).

A – Broodstock are conditioned in the hatchery at 20-22?C for 2 to 4 weeks during late winter, early spring. A constant flow of seawater is maintained through the tank and food is added daily. B – The appearance of a fully mature scallop; the orange coloured ovary and white testis occupy

the distal and proximal parts of the gonad respectively. The adductor muscle is centre right and the brown-coloured tissue includes the gills and mantle, which have been raised to expose the gonad.

C – Up to 20 scallops are spawned at a time in transparent plastic trays of approximately 75 x 45 x 5 cm water depth. The trays contain sufficient 1 ?m filtered seawater to fully cover the scallops. One is chilled to 12°C with ice packs and the other is heated to 25 to 27?C with a 150W aquarium heater. The scallops are cycled between the two temperatures as explained in the text.

D – Staff keep careful watch to identify scallops as they begin to spawn in the warm water tray. Spawners are rinsed with filtered seawater and transferred individually to labelled plastic beakers containing 0.5 to 1 l of seawater in other trays acting as warm water baths at the spawning temperature.

E – After liberating sperm, scallops will suddenly switch to spawning orange coloured eggs. It is important that as soon as the switch is made scallops are removed, rinsed and returned to clean beakers containing filtered seawater to continue egg liberation. If egg production is swift and prolific, sperm from other scallops will often be added at this time.

F – Eggs of good quality, determined by microscopic examination, are pooled in 10 l buckets. Note the perforated plastic plunger used to gently agitate the bucket contents to keep the fertilized eggs in suspension. The bucket may contain between 5 and 10 million eggs – judged “by eye”.