6.2 Generalities on coastal lagoons

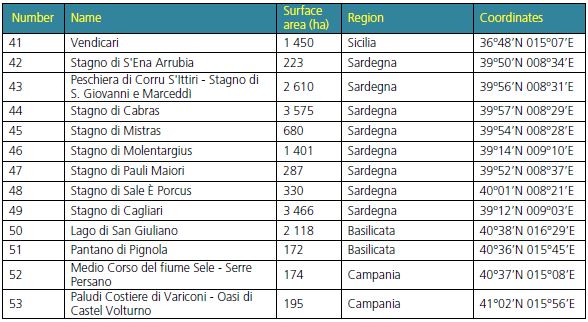

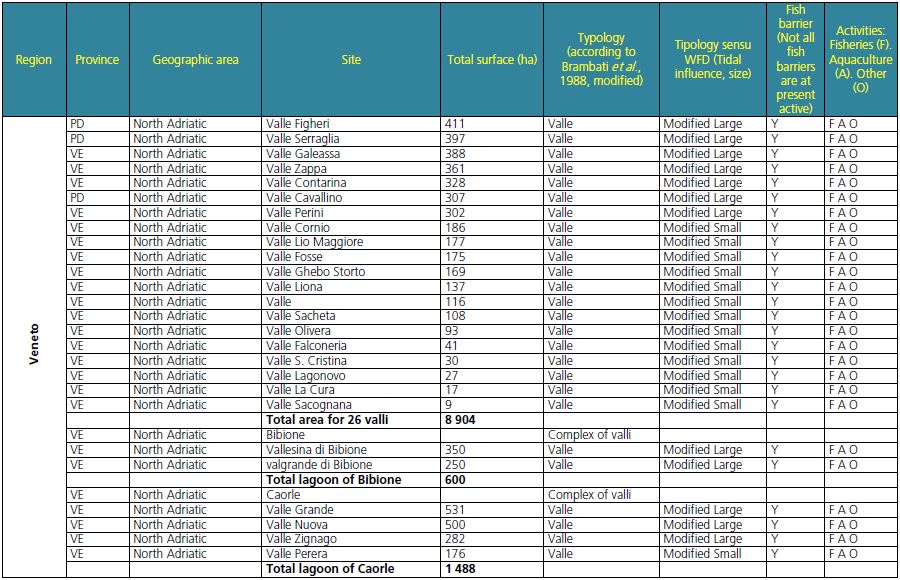

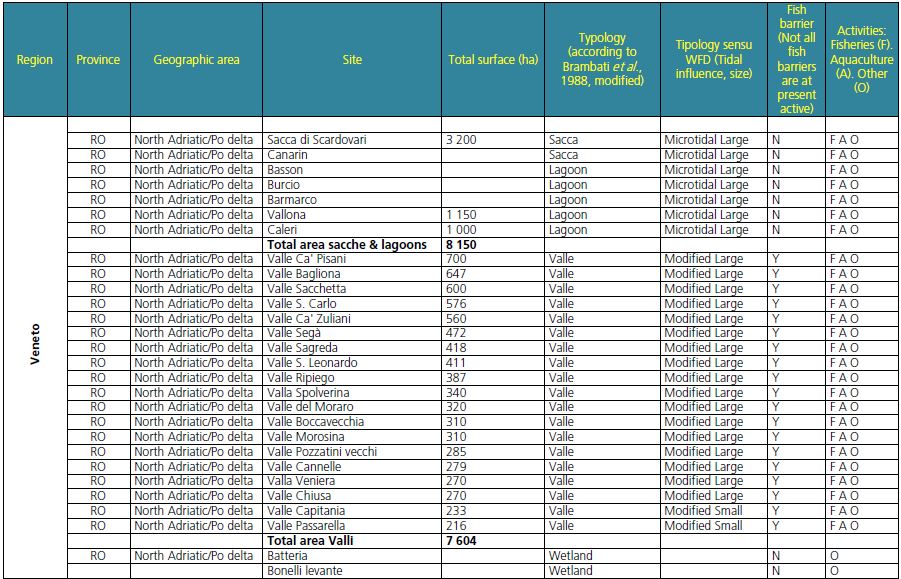

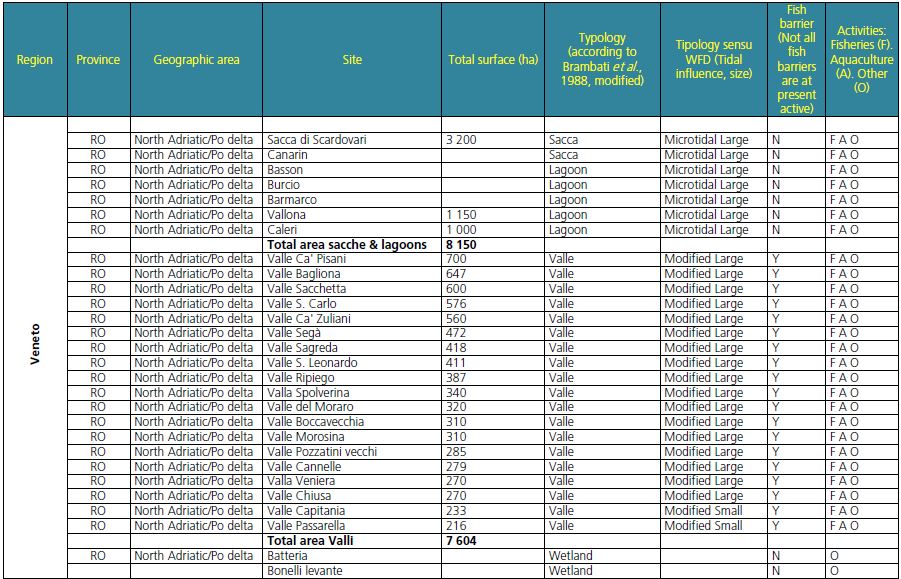

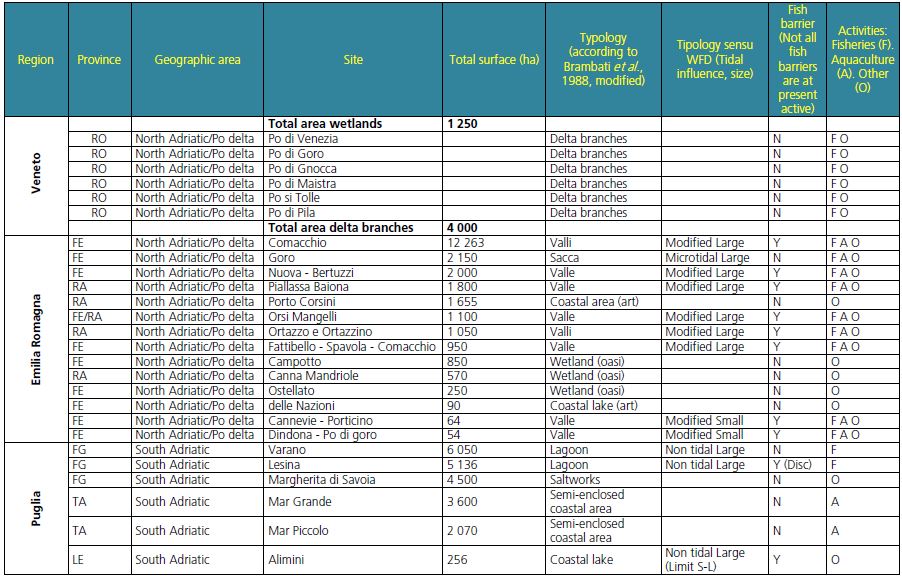

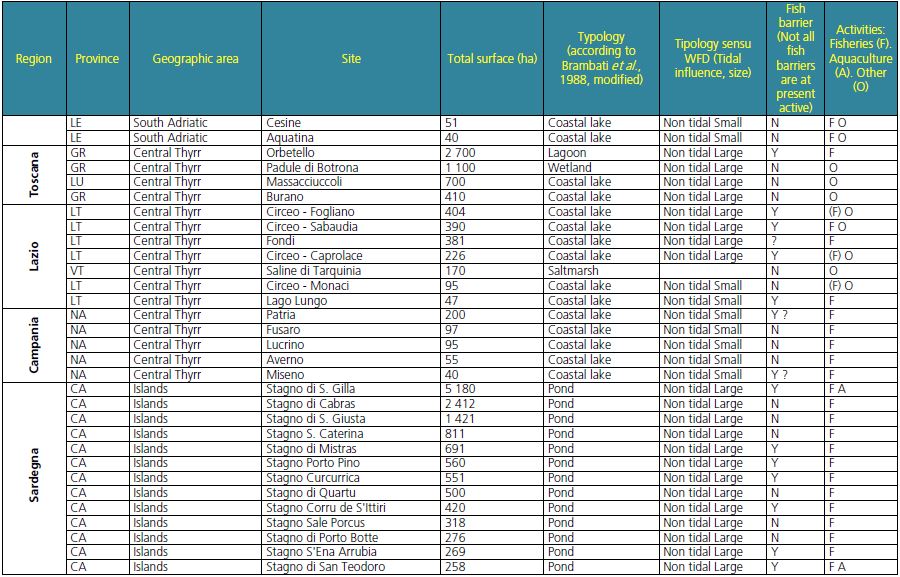

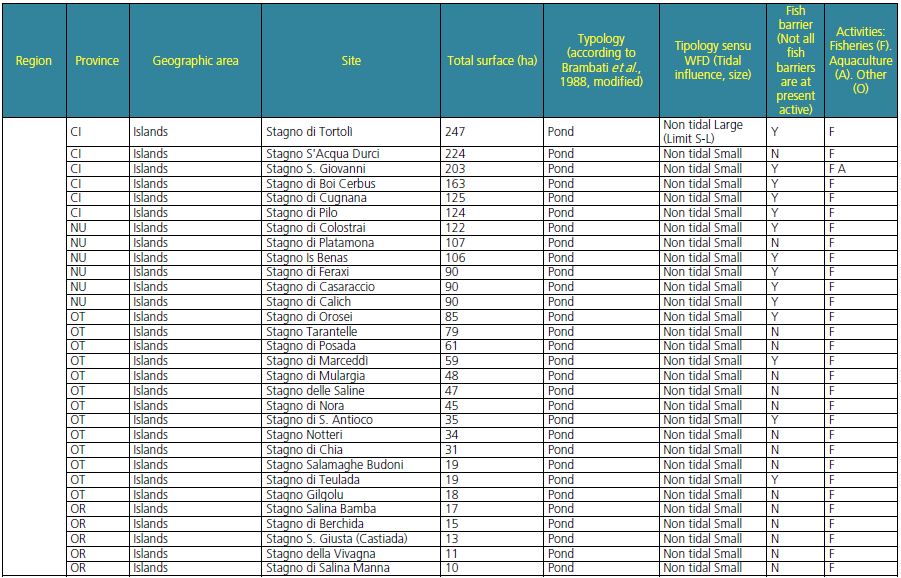

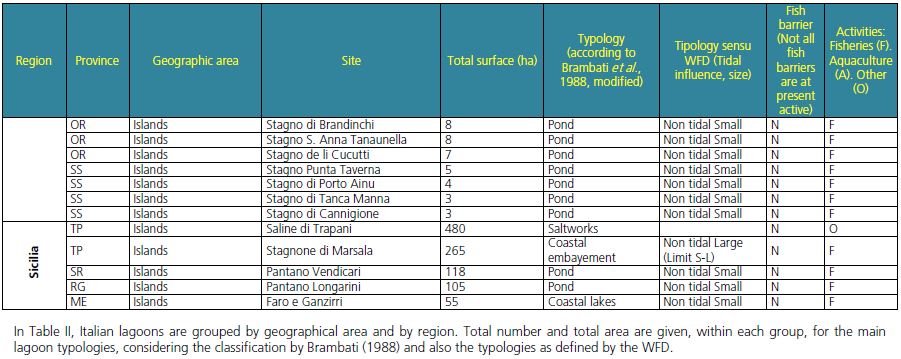

Overall, Italian coastal lagoons add up to more than 190 coastal lagoons, including all typologies, i.e. lagoons, coastal lakes and ponds, sacche, delta areas and valli. The complete list of the coastal lagoons is reported in Table I; the revision was made for the present project by consulting the most recent literature and the official websites (Ispra, Ministero dell’Ambiente) for the complete list and then verifyied, for presence and surface, by the geographic information system (GIS). Inconsistencies in numbers or surfaces among different sources usually are due to the fact that some coastal lagoons, specifically the valli in the northern Adriatic area, often undergo maintainance works or reorganizations due to change in ownership.

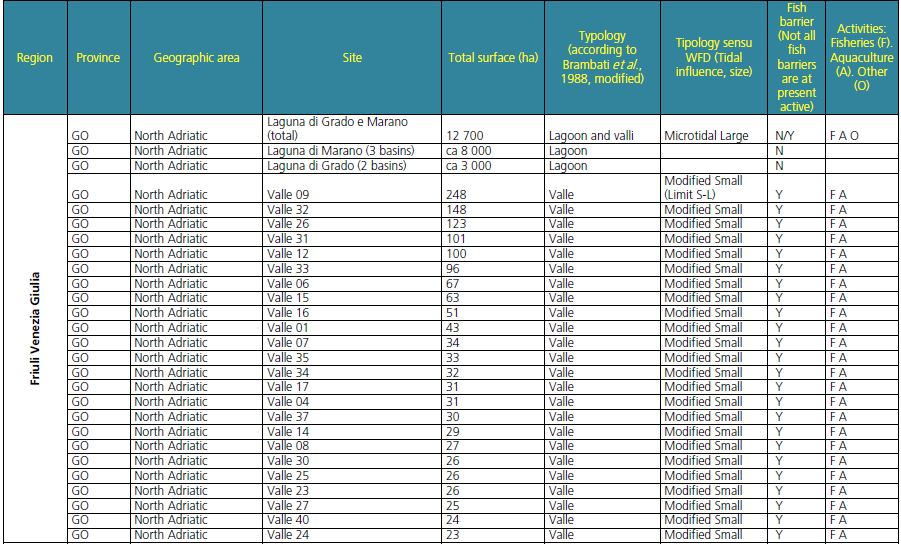

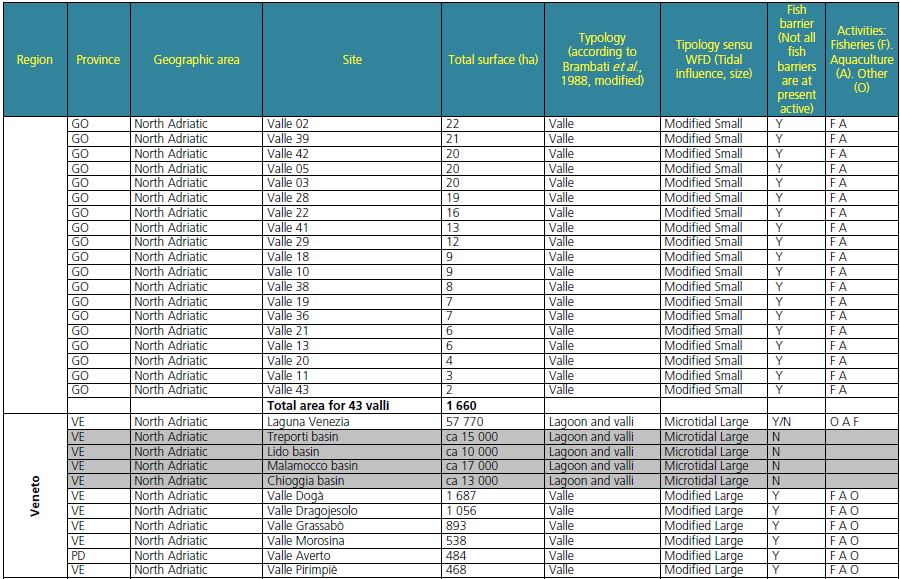

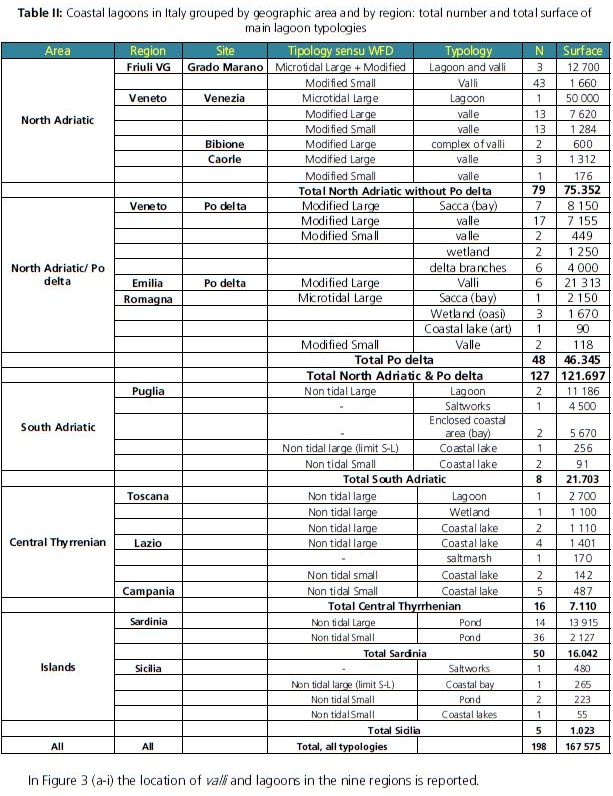

In Table II, coastal lagoons are listed by geographic area and by Region, and within each group they are listed by 1 surface area. Lagoon surfaces range from the over 57 000 ha of the lagoon of Venice, the 17 largest of the Mediterranean, to the few hectares of some valli of the northern Adriatic area and of many Sardinian ponds.

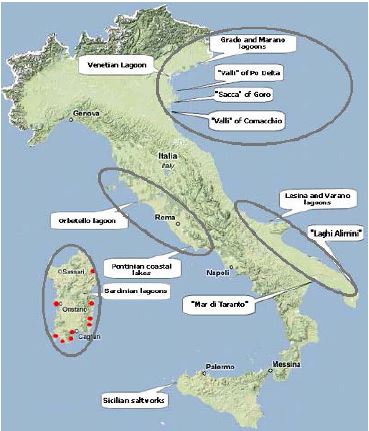

“Lagoon” is a term used in Italy only for large lagoons, 5 000–50 000 ha, such as the microtidal lagoons of the northern Adriatic (Venice, Grado, Caorle, Marano), for the non tidal large lagoons of the southern Adriatic (Varano and Lesina) and for the lagoon of Orbetello (Tuscany). They vary in depth between 2 and 5.5 m, salinity ranges between 7–47 ‰ and productivity between 70 and 150 kg/ha.

In the northern Adriatic area (in the Friuli Venezia Giulia, Veneto and Emilia Romagna regions), the valli, lagoon sectors enclosed for fish culture by means of earthen embankments, are present. Main features of a valle include, besides embankments, sluice gates, internal canalization, basins for fish collection and wintering and fish barriers (lavorieri). Vallicultura is a term that indicates the traditional management model carried out in the northern Adriatic valli, based on hydraulic management, dredging, enhancing of fisheries by stocking and fish capture at the lavoriero. Their surface varies from very small (1–2 ha) to more than 10 000 ha (usually a complex of valli, such as the famous valli of Comacchio). Depth is 0.6 m average, max 2 m; salinity ranges between 10–40 ‰ and productivity: 20–150 kg/ha. Other tipologies typical of the northern Adriatic are the sacche, brackish water areas typical of the Po delta: these are wide bays communicating with the sea and only partially enclosed by sand banks. Fishing activities are carried out in the sacche, and shellfish culture in most of them. Their surfaces are about 2 600–3 200 ha, usually shallow, depth 0.5–2 m, their salinity ranges between 18 and 35 ‰. Productivity for shellfish culture can reach 15 000 kg/ha (Sacca di Goro).

In Italy, the term “coastal lake” refers to the medium-size lagoons and to the coastal basins in communication with the sea by one or more channels. The term is often used for the lagoons of the central Thyrrhenian area.

Usually, only artisanal fisheries are carried out within coastal lakes. This typology overlaps with the stagni, ponds that also indicate medium-sized basins.

The term stagno (pond) is almost exclusively used for the lagoons of Sardinia. Artisanal fisheries is performed in these stagni, and shellfish as well in some of them. Over 60 stagni are present in Italy, mostly concentrated in Sardinia.

Figure 2. Location of the main coastal lagoons in Italy (from Marino et al., 2009)

This simple classification probably gives rise to a certain improper use of the terms, a confusion that stems in part from local names of commonly used terms, in Italy as elsewhere in the Mediterranean. According to the classification proposed by Brambati (1988), the key parameter that allows to distinguish between coastal lagoons and ponds is the presence of tidal range, absent in the lagoons and coastal ponds. Recently, the problem of classification of the types defined in the Mediterranean lagoons has become particularly topical in relation to some criteria introduced by the WFD, 60/2000/CE. The Directive introduced a new terminology for aquatic systems. In particular, transitional waters are defined as "surface water bodies near the mouth of a river, the saline because of their proximity to coastal waters but substantially influenced by freshwater flows." According to the definition given by the WFD for the transitional waters, and to the interpretation given to it (De Wit et al., 2007), most Mediterranean lagoons, and all the Italian ones, fall within the category of coastal lagoons. At the national level, as a part of the lentic transitional waters, Italian lagoons can be classified according to the influence of the tide (micro-tidal lagoons, with a range exceeding 50 cm, and non-tidal or nano-tidal (Tagliapietra and Volpi Ghiradini, 2006) lagoons, with a range of less than 50 cm), while a second level of subdivision is based on size, discriminating between lagoons with a surface area greater or less than 300 ha (Basset et al., 2004).

Thus, within the typologies sensu WFD, ponds (stagni) and coastal lakes comprise small and large non tidal basins, and the valli are considered modified water bodies. With specific regard to the typing of the Italian coastal water bodies, a characterization based on geological features (Cataudella and Tancioni, 2007), also adopted for the realization of a "geographic information system of the Italian coastal ponds", can also be the following (Valloni et al., 2006):

• Pond (stagno): marine-adjacent basin without natural channels for communication with the sea (this definition is also valid for coastal lakes, laghi costieri)

• Pond system: pond integrated with wetlands in the shoreline and/or with swamps; 118

• Lagoon: marine-adjacent basin separated from the sea by a sand barrier stable and well defined, interrupted by one or more channels;

• Lagoon system: lagoon integrated with wetlands in the shoreline and/or with swamps; • Bay: marine basin with a single, wide mouth opening towards the sea (includes the delta water bodies called sacche).

Table I: Complete list of the coastal lagoons in Italy, by region, province and geographic area: surface, typology and use (presence/absence of fish barriers, activities in the lagoon)

In Table II, Italian lagoons are grouped by geographical area and by region. Total number and total area are given, within each group, for the main lagoon typologies, considering the classification by Brambati (1988) and also the typologies as defined by the WFD.

Table II: Coastal lagoons in Italy grouped by geographic area and by region: total number and total surface of main lagoon typologies

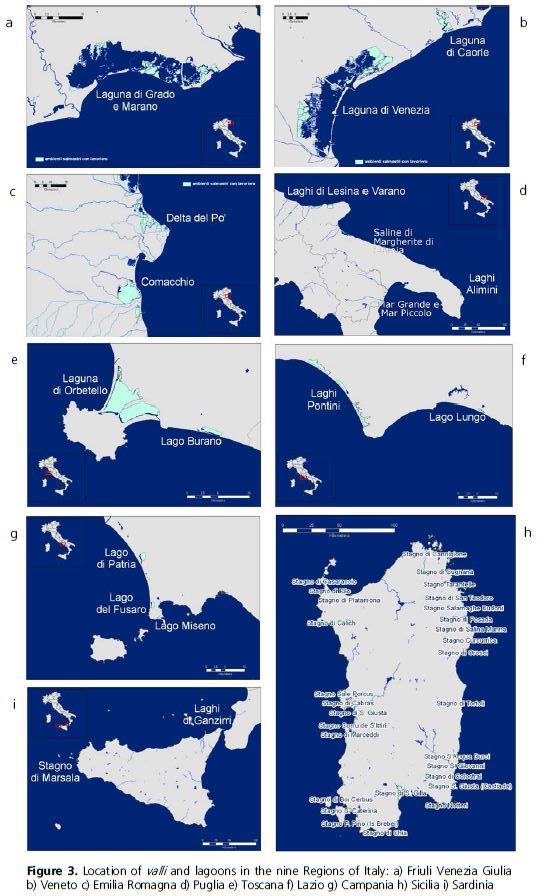

Figure 3. Location of valli and lagoons in the nine Regions of Italy: a) Friuli Venezia Giulia b) Veneto c) Emilia Romagna d) Puglia e) Toscana f) Lazio g) Campania h) Sicilia i) Sardinia

In almost all Italian lagoons, capture fisheries and/or aquaculture activities are carried out, with the exception of a few lagoons that are protected areas. On the whole, production from lagoon environments in Italy amounts to 2 787 tonnes of fish and 35 007 tonnes of shellfish for 2009 (Unimar, 2009).

Fisheries and extensive aquaculture carried out in coastal lagoons partially overlap with regards to culture techniques, and in statistics as well, therefore it is difficult to separate productions from the different typologies.

Extensive farming is a rearing system based on the use of the trophic resources of coastal ecosystems targeting the production of fish and shellfish and excluding human intervention in feeding. Several forms of extensive aquaculture border between fishing and culture-based fisheries techniques. Key features to discriminate between coastal lagoon fisheries and extensive aquaculture are the type of lagoon ownership, the presence of systems for hydraulic control and water management (weirs, locks) and the presence of fixed trapping systems (e.g. fish traps and barriers ). A typical extensive aquaculture typology in Italy is the vallicoltura practised in the vally of the North Adriatica area.

In the valli, management for fish production is still traditional, configured as an extensive poly culture system with relatively low productions and reduced operating costs.

In these extensive systems, the growth of fish is due only to the natural productivity of the aquatic environment. These low-energy aquaculture techniques have the side effect of contributing, through the management of the environment, to habitat conservation of sandbanks and shallow lagoon sections. Hunting is also performed in the valli, in relation to a high density and variety of water birds.

Shellfish farming is another aquaculture practice that occurs in coastal lagoons of Italy. Venericulture productions in coastal lagoons Italy relies mainly on the Manila clam Ruditapes philippinarum in the northern Adriatic, in the lagoon of Venice. Less important productions of the indigenous specie R. decussatus are restricted to few areas in Sardinia.

Manila clam was first introduced in Venice in 1983 using artificially reproduced seed from an English nursery. Subsequently, successful introductions were obtained in several northern Adriatic brackish environments such as Po delta lagoons of Caleri, Scardovari, Goro and in the Grado-Marano lagoon; the new species acclimatised and spread out rapidly leading to colonization of large areas and settlement of self-sustaining populations.

Manila clam farming is currently the most important activity in the fishery industry of the north western Adriatic, and Italy has become the most important producer in Europe and in the Mediterranean.

Mussel culture is also practiced in coastal lagoons. The areas traditionally devoted to mitiliculture are the “Golfo di Taranto” (Puglia), La Spezia (Liguria), the lagoon of Venice (Veneto) and litorale Flegreo (Campania), but this activity has become an important activity in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, in Sardinia, Emilia-Romagna and on the East coast of Apulia.

In many lagoons, a multifunctional pattern of exploitation is present, in particular when towns insist on the coastal basin. In this sense, the lagoon of Venice is an extreme example, because nowadays in this large lagoon every possible use of land and water is achievable, and this has strongly influenced the lagoon ecosystem. Land based activities that deliver nutrients, heavy metals and other pollutants, fishing and aquaculture activities, in particular clam harvesting, ground-water and gas extraction, past and present interventions, combined to phenomena such as subsidence, eustatism, transportation and climatic conditions represent different stressors acting on the lagoon ecosystem.

Among the many activities carried out on coastal lagoons in Italy, tourism is one of the activities that can interest these environments, with patterns that can be also very different. In some cases, touristic activities concern sites or or near the lagoon: this is the case of lagoons such as Lesina or Orbetello or of many Sardinian ponds, where the area is frequented by many tourists in summer months, with attendance that depends on the accommodation capacity of the neighbouring towns. In other cases, there is a direct involvement of the lagoon enterprise in the touristic activity, that is the case for example of many ittioturismi in Sardinia and in other regions as well, where the fishers’ cooperatives directly manage restaurants, fishing activities, boats tours, etc.

In some lagoons that are included within National or Regional Parks, there is a strong involvement in the conservation of wildlife and biodiversity. This is the case of the Pontinian coastal lakes (Monaci, Fogliano and Caprolace), that are included within the boundaries of the Circeo National Park, and where capture fisheries are now banned. In other Parks, some fishing activities continue to be practised, as in the Lesina lagoon, included in the Gargano National Park, or in the Valli di Comacchio, included in the Parco Regionale delta Po.

In the latter, these activities are maintained with the aim of conserving tradition and culture.

The legal framework of coastal lagoons in Italy is not unambiguous, and different frameworks exist. Ownership is in most case public, of the Italian State (demanio), and this concerns most lagoons, but in some cases the ownership is of the Municipality. Competent authorities are in most cases the municipalities, in some cases assisted by specific Authorities involved in lagoon management. This is the case of the Orbetello lagoon, where the Orbetello Lagoon Environmental Reclamation Authority, OLERA, was created to assist in the management of the lagoon. With regards to the legal framework, the lagoon of Venice represents an extreme situation, complicated by the lagoon extension and by the multiple uses of the lagoon, and therefore by the consequent multiple competences. The situation is further complicated by environmental issues such as the lowering of the lagoon level with respect to the sea, which has brought about the need of extraordinary interventions for the safeguarding of the town of Venice. The complexity of the lagoon governance framework can be easily understood by the high number of Institutions that have competent authority in the Venice lagoon territory.

In some cases the lagoons are private property. Such is the case of most valli in the Venetian area and in the other adjoining regions. This is an issue that is being addressed by an ongoing legal debate. A case for which the private ownership has been definitively established concerns the Sabaudia coastal lake in Lazio, private property of the Scalfati family since 1882.

In most cases, fishing rights are bestowed to local companies or cooperatives of professional fishers, but in some cases they can be granted by civic use to the citizens of the local Municipality (Lesina, Orbetello).

The protection of coastal wetlands, including lagoons, is a priority in the policy of conservation in the Mediterranean and in Italy as well. Given the multifunctional nature of the lagoon ecosystems, which includes among the main uses environmental conservation, lagoons have been the objective of many conventions and international directives. Among these, the first in chronological order is the Ramsar Convention (1975). More recently, the Birds Directive (79/409/EEC) and Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC) are fundamental tools for the protection of biodiversity. The implementation at the the national level of this Directive, through the Natura 2000 network, led to the identification of numerous SCIs and SPAs that coincide with most Italian lagoon environments.

According to the national inventory of wetlands, drawn by Ispra in collaboration with the Ministry of Environment and ARPA Toscana, there are 1 511 wetland sites in Italy. The total extension amounts to 771 125 ha. 48 percent are lakes and rivers, 32 percent are marine and coastal environments and 20 percent artificial wetlands. Of these, only 6 percent is still not protected. Among these, 53 sites are recognized as internationally important under the Ramsar Convention (Table III, Fig. 4). Of the 53 Ramsar sites, 31 are coastal lagoon environments, i.e. more than 80 percent. The coastal lagoons listed as Ramsar sites amount to 60 296 ha out of the total 67 575 ha of Italian coastal lagoons, i.e. 36 percent of the total surface of lagoons in the country.

Table III: List of the sites protected under the Ramsar Convention (provided by the Italian Ministry of the Environment)