5.2.2 Dietary considerations

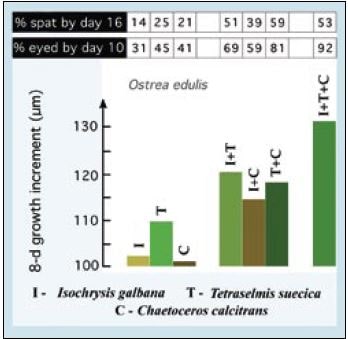

Mixed algal diets are beneficial. A combination of two or three high nutritional value species including a suitably sized diatom and a flagellate invariably provide improved rates of larval growth and development than do single species diets (Figure 68). They also improve spat yields and influence the subsequent performance of spat in terms of both growth and survival.

Figure 68: Growth (in an 8-day period), development (% eyed larvae by Day 10) and settlement (percentage spat of the initial larval number at Day 0) of Ostrea edulis larvae fed various single and mixed diets of the three algal species indicated. Values are the means of a large number of trials.

Not all of the suitably sized and readily cultured algal species available from culture collections are of good food value to larvae. But generally those that are valuable foods for the larvae of one species will be of similar value to others. There are exceptions to this rule as will be explained later. The food value of a particular alga is determined not only by its biochemical composition but also its “ingestability” and digestibility. For example, diatoms with long, silicaceous spines may be difficult to ingest and be an irritant to be expelled by larvae closing their shell valves. Some varieties of Phaeodactylum are a good case in point. Other species, such as Chlamydomonas coccoides have thick cell walls that render them almost indigestible. Yet others, including Dunaliella tertiolecta, lack certain essential highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFAs) required for larval development and while digestible, have little or no nutritional value.

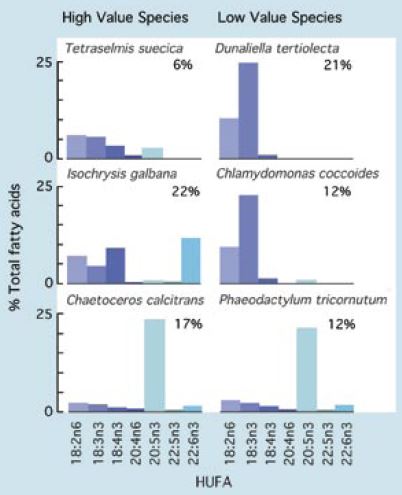

A comparison of the HUFA profiles of a number of algal species that are either good or poor foods for larvae is given in Figure 69. Also shown are values of total lipid content as a percentage of ash-free dry weight.

Figure 69: Comparison of total lipid as a percentage of ash-free dry weight and the relative abundance of various highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFAs) in a number of algal species of both high and low nutritional value to bivalve larvae.

High food value species tend to have relatively high proportions of either 20:5n3 (EPA – eicosapentaenoic acid) or 22:6n3 (DHA – docosahexaenoic acid) compared with many of the poor value species. If these components are lacking in the diet, it appears that the larvae of most bivalves have either no or only a limited ability to synthesise them from less highly unsaturated precursors. It is the case for many of the diet fastidious species that feeding a combination of species rich in either EPA or DHA (or both) will provide the best results. Larvae of clams tend to be less dependent in this respect than those of oysters or scallops.

The relative proportions of HUFAs and the overall lipid content of species of algae useful for hatchery production vary according to phase of the culture cycle and also culture conditions, which differ from hatchery to hatchery. However, species that are of good nutritional value in one hatchery situation will always be of similar value elsewhere given reasonably good attention to details of the culture conditions.

The various diatom species commonly grown in hatcheries have very similar HUFA profiles, all being rich in EPA. Total quantities of particular fatty acids in the different diatom species are somewhat variable. They tend to be higher in cultures entering the stationary phase than during exponential growth.

Among the small cell-size brown flagellates, Pavlova lutherii has a similar HUFA profile to Isochrysis galbana (Figure 69) but tends to have more DHA. In contrast, the T-ISO clone of Isochrysis has only 50 to 70% of the DHA of Isochrysis galbana when grown in side-by-side culture in the same conditions of light and nutrients. T-ISO tends to be grown in more hatcheries than its near relatives because it is easier to culture year round and is tolerant to higher temperatures. Useful substitutes for Tetraselmis are species of Pyramimonas (e.g. P. obovata and P. virginica). They have HUFA profiles intermediate between Tetraselmis and Isochrysis but can be difficult to culture at certain times of year.