1.2. Characteristics

Filamentous algae and seaweeds have an extremely wide panorama of environmental requirements, which vary according to species and location. Ecologically, algae are the most widespread of the photosynthetic plants, constituting the bulk of carbon assimilation through microscopic cells in marine and freshwater.

The environmental requirements of algae are not discussed in detail in this document. However, the most important parameters regulating algal growth are nutrient quantity and quality, light, pH, turbulence, salinity and temperature. Macronutrients (nitrate, phosphate and silicate) and micronutrients (various trace metals and the vitamins thiamine (B1), cyanocobalamin (B12) and biotin) are required for algal growth (Reddy et al., 2005). Light intensity plays an important role, but the requirements greatly vary with the depth and density of the algal culture. The pH range for most cultured algal species is between 7 and 9; the optimum range is 8.2–8.7. Marine phytoplankton are extremely tolerant to changes in salinity. In artificial culture, most grow best at a salinity that is lower than that of their native habitat. Salinities of 20–24 ppt are found to be optimal. Lapointe and Connell (1989) suggested that the growth of the green filamentous alga Cladophora was limited by both nitrogen and phosphorus, but the former was the primary factor. Hall and Payne (1997) found that another green filamentous alga, Hydrodictyon reticulatum, had a relatively low requirement for dissolved inorganic nitrogen in comparison with other species.

Rafiqul, Jalal and Alam (2005) found that the optimum environment for Spirulina platensis under laboratory conditions was 32 ?C, 2 500 lux and pH 9.0. Further information on the environmental requirements of algae cultured for use in aquaculture hatcheries is contained in Lavens and Sorgeloos (1996). The environmental requirements of cultured seaweeds are discussed by McHugh (2002, 2003).

A brief description of some of the filamentous algae and seaweeds that have been used for feeding fish, as listed in Tables 1.1–1.3, is provided in the following subsections.

1.2.1 Filamentous algae

Filamentous algae are commonly referred to as ‘pond scum’ or ‘pond moss’ and form greenish mats upon the water surface. These stringy, fast-growing algae can cover a pond with slimy, lime-green clumps or mats in a short period of time, usually beginning their growth along the edges or bottom of the pond and ‘mushrooming’ to the surface. Individual filaments are a series of cells joined end to end which give the thread-like appearance. They also form fur-like growths on submerged logs, rocks and even on animals. Some forms of filamentous algae are commonly referred to as ‘frog spittle’ or ‘water net’.

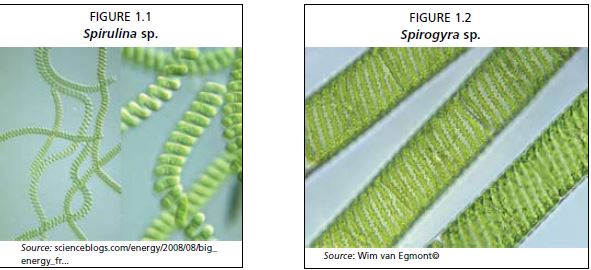

Spirulina, which is a genus of cyanobacteria that is also considered to be a filamentous blue-green algae, is cultivated around the world and used as a human dietary supplement, as well as a whole food. It is also used as a feed supplement in the aquaculture, aquarium, and poultry industries (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1

Spirulina sp.

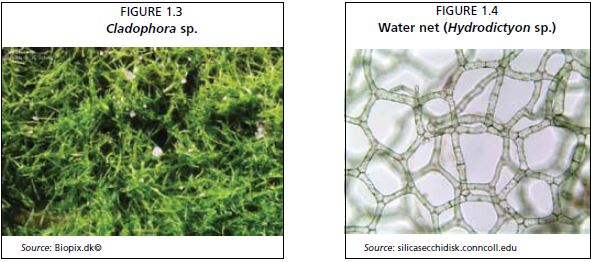

Figure 1.2 Spirogyra sp.

Source: scienceblogs.com/energy/2008/08/big_ energy_fr...

Source: Wim van Egmont©

Spirogyra, one of the commonest green filamentous algae (Figure 1.2), is named because of the helical or spiral arrangement of the chloroplasts. There are more than 400 species of Spirogyra in the world. This genus is photosynthetic, with long bright grass-green filaments having spiral-shaped chloroplasts. It is bright green in the spring, when it is most abundant, but deteriorates to yellow. In nature, Spirogyra grows in running streams of cool freshwater, and secretes a coating of mucous that makes it feel slippery. This freshwater alga is found in shallow ponds, ditches and amongst vegetation at the edges of large lakes. Under favourable conditions, Spirogyra forms dense mats that float on or just beneath the surface of the water. Blooms cause a grassy odour and clog filters, especially at water treatment facilities.

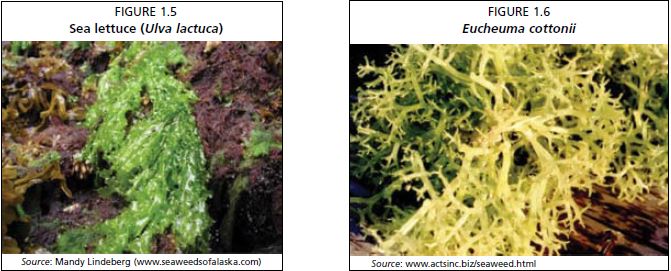

Cladophora (Figure 1.3) is a green filamentous algae that is a member of the Ulvophyceae and is thus related to the sea lettuce (Ulva spp.). The genus Cladophora has one of the largest number of species within the macroscopic green algae and is also among the most difficult to classify taxonomically. This is mainly due to the great variations in appearance, which are significantly affected by habitat, age and environmental conditions. These algae, unlike Spirogyra, do not conjugate (form bridges between cells) but simply branch.

Figure 1.3

Cladophora sp.

Source: Biopix.dk©

Figure 1.4

Water net (Hydrodictyon sp.) Source: silicasecchidisk.conncoll.edu

6 Use of algae and aquatic macrophytes as feed in small-scale aquaculture – A review

Another green filamentous alga, Hydrodictyon, commonly known as ‘water net’, belongs to the family Hydrodictyaceae and prefers clean, eutrophic water. Its name refers to its shape, which looks like a netlike hollow sack (Figure 1.4) and can grow up to several decimetres.

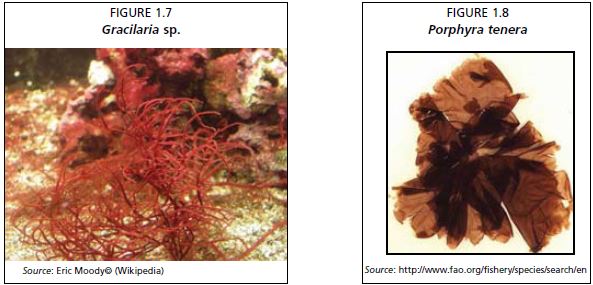

1.2.2 Seaweeds

Ulva are thin flat green algae growing from a discoid holdfast that may reach 18 cm or more in length, though generally much less, and up to 30 cm across. The membrane is two cells thick, soft and translucent and grows attached (without a stipe) to rocks by a small disc-shaped holdfast. The water lettuce (Ulva lactuca) is green to dark green in colour (Figure 1.5). There are other species of Ulva that are similar and difficult to differentiate.

Figure 1.5

Sea lettuce (Ulva lactuca)

Source: Mandy Lindeberg (www.seaweedsofalaska.com)

Figure 1.6

Eucheuma cottonii

Source: www.actsinc.biz/seaweed.html

It is important to recognize that the genera Eucheuma and Kappaphycus are normally grouped together; their taxonomical classification is contentious. These are red seaweeds and are often very large macroalgae that grow rapidly. The systematics and taxonomy of Kappaphycus and Eucheuma (Figure 1.6) is confused and difficult, due to morphological plasticity, lack of adequate characters to identify species and the use of commercial names of convenience. These taxa are geographically widely dispersed through cultivation (Zuccarello et al., 2006). These red seaweeds are widely cultivated, particularly to provide a source of carageenan, which is used in the manufacture of food, both for humans and other animals.

Gracilaria is another genus of red algae (Figure 1.7), most well-known for its economic importance as a source of agar, as well as its use as a food for humans.

Figure 1.7

Gracilaria sp.

Source: Eric Moody© (Wikipedia)

Figure 1.8

Porphyra tenera

Source: http://www.fao.org/fishery/species/search/en

The red seaweed Porphyra (Figure 1.8) is known by many local names, such as laver or nori, and there are about 100 species. This genus has been cultivated extensively in many Asian countries and is used to wrap the rice and fish that compose the Japanese food sushi, and the Korean food gimbap. It is also used to make the traditional Welsh delicacy, laverbread.