3.2 Methods to monitor and forecast blooms

Jellyfish blooms became a matter of concern in the early 1980s in the whole Mediterranean sea. On that occasion, UNEP launched a programme and considered them a sort of biological pollution, promoting jellyfish research within the framework of the MED POL initiative. The results of these researches were summarized in UNEP (1984; 1991). On that occasion, however, researchers were not much experienced on these topics, and the expertise was more or less improvised.

The episodic occurrence of such phenomena, in fact, prevented the building of specific capacities on this topic, since they would have been underutilized for most of the time. Marine scientists focused more on events that were rather predictable, such as phytoplankton blooms or crustacean zooplankton blooms, not to speak about fisheries sciences. The researchers that had previous experience on gelatinous plankton, furthermore, usually dealt with small jellyfish (i.e. the Hydrozoa) that are more stable in presence, albeit they do not have the same impact of the large jellyfish, in case of blooms.

Long term samplings, however, are usually carried out at various parts of the world and the examination of the samples might give an indication of the taking over of gelatinous plankton on the rest of the trophic networks, as highlighted by Brodeur et al. (1999) for the Bering Sea and by Licandro et al. (2010) for the Northeast Atlantic and the Mediterranean Sea. It is often the case, however, that large gelatinous organisms are considered as a nuisance for plankton sampling, since they clog the nets and spoil the rest of the plankton. Thus, it can happen that sampling sessions are just interrupted, waiting for the bloom to disappear! In this way precious information is usually lost and, furthermore, such behavior by researchers suggests that the lack of records of blooms might not necessarily mean that the blooms did not occur but that they were simply not recorded, even deliberately.

The UNEP-MED POL project suddenly came to an end due to the end of the jellyfish outbreaks of the early 1980s, and no other project on gelatinous plankton has been launched in the Mediterranean region so far. Only recently, due to the increase of gelatinous plankton outbreaks, activities did start again. The most noticeable one is the already mentioned Jellywatch, launched by CIESM in Italian waters, that was supported by the magazine Focus: http://www.focus.it/meduse/

In Catalunya, the local government launched Projecte Medusa:

http://www.icm.csic.es/bio/medusa/index.html

At Malta the project is called Spot the Jellyfish:

http://193.188.45.233/jellyfish/index.html

In Ireland it is Ecojel:

http://www.jellyfish.ie/index.asp

The best structured one is the Calalan Projecte Medusa, with relatively high funding that led to the availability of well-equipped laboratories to rear jellyfish under controlled conditions, reconstruct their life cycles, and make experiments on their physiological requirements. In 2011, the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme financed the project “Vectors of change”, and one task of the project regards just the investigation of gelatinous plankton blooms at European scale. Other EU projects, namely Perseus and CoCoNet, still within the Seventh Framework Programme, do have the study of gelatinous plankton among their scopes, supporting the concept that was initiated under the CIESM umbrella.

The study of gelatinous macrozooplankton requires completely different techniques from those employed for crustacean plankton (see Purcell, 2009 for a review). In general, the current ways that scientists employ to assess the presence and the abundance of gelatinous macrozooplankton are visual censuses from various means:

1. Blue diving: divers stay at a given depth, linked to a rope fixed to a buoy or a boat, and count jellyfish in a fixed period of time (Hamner, 1975). Samples are obtained by using plastic bags.

2. From boats: cruises with boats (from small vessels to ferries) follow predefined paths, and jellyfish are counted during these mini-cruises, by identifying them from the boat. Samples can be obtained from small vessels by using buckets or plastic bags.

3. From airplanes: jellyfish are visible from small airplanes flying at low heights and large areas can be inspected in a relatively short time (Houghton et al., 2006). 4. From beaches: it is possible to see stranded jellyfish by walking along beaches, also near shore gelatinous plankton is visible from the coast.

5. From submersibles: this very expensive method is revealing an astonishing abundance and diversity of gelatinous plankters in deep waters. Photographic records and collections of specimens are possible and the chances to find new species are high (Larson et al., 1992).

6. By videocameras: this allows prolonged observation periods from a fixed station (Benfield et al., 1996).

Echosound measures are also possible, even though it is not so easy to identify the species in question (e.g. Brieley et al., 2005).

Radio tracking is being used to follow tagged individuals of large and sturdy species, leading to precious information on their movement patterns (e.g. Gordon and Seymour, 2009). This implies that some individuals are captured, tagged, and released.

Licandro et al. (2010) used data from the Continuous Plankton Recorder to reconstruct jellyfish abundances in the historical period sampled by the CPR. These automatic methods, however, might not account for blooms of large organisms that are distributed in the water column in a spaced manner, as it is often the case for gelatinous plankters.

Citizen science (Silvertown, 2009) is an alternative method to evaluate the presence and abundance of gelatinous macrozooplankton.

The advantages are:

• public involvement in science

• coverage of large areas almost indefinitely

• no costs

• large amount of data

• easy documentation through pictures

• if a species is recorded, it means that it occurs at a given place and at a given time • if a species is not recorded when other species are recorded, chances are good that that species was really absent

The disadvantages are:

• great efforts in mass media involvement, requiring good communication skills • not homogeneous data quality

• unknown research effort: if no species are recorded, it does not mean that they were absent (negative data can be due to absence of observers)

• mostly based on shore observations

The advantages of citizen science approaches are especially evident for gelatinous plankton since people are very easily aware of it, and the species in the Mediterranean Sea are mostly easy to identify with some reliability. Citizen science has been used to monitor jellyfish presence along the Italian coastline

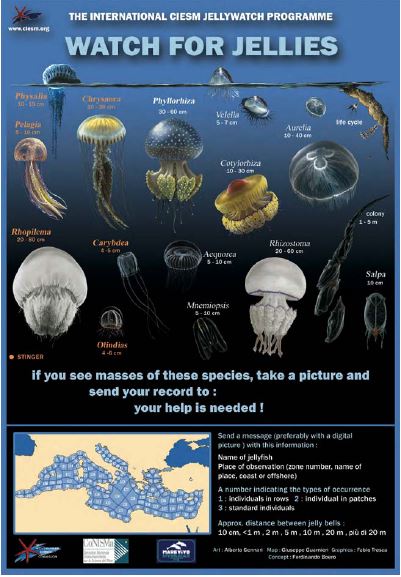

(8 500 km) during 2009–2011 and the results were impressive, with thousands of records of all the main species, the records of new species from the Mediterranean or for the Italian fauna. Citizen science is a very good tool to assess the presence of gelatinous plankton, especially along the coast. The CIESM Jellywatch, carried out by F. Boero for three years (2009–2011) was based on a poster (Fig. 20) distributed across Italy through an intense media campaign. The results of the Jellywatch (carried out especially in Italy and Israel) led to the records of new species from the Mediterranean or to a better evaluation of their distribution, with new records from the western basin, showing the expansion of tropical species that thrived already in the Levantine basin.

Figure 20. The poster of the CIESM jellywatch (2009 version). (Concept by Ferdinando Boero, art by A. Gennari, graphics by F. Tresca).

The discovery of abundant populations of Mnemiopsis leydi both in Israel (Galil et al., 2009) and in Italy (Boero et al., 2009) showed that the alien ctenophore successfully colonized the whole Mediterranean. The result was covered by the media of the whole world, reaching the cover of Time Magazine (Faris, 2009) (Fig. 21). The campaigns of 2010 and 2011 were even more successful due to the involvement of the popular science magazine Focus, that even opened a web page dedicated to the jellywatch, and published Meteomedusa, a weekly report on the presence of jellyfish along the

Italian coast, ensuing from the records of the readers. In 2011, a smartphone app of meteomedusa was launched and it was downloaded 26 000 times.

Figure 21. Jellyfish in the Mediterranean hit the cover of Time magazine, on 4th November 2009.