9 Artificial reef management: control, surveillance and maintenance

Like other types of aquatic environments, artificial reefs may require post?installation management to make sure that they provide the desired outcomes for both biological resources and users. Additionally, effective management can help reduce potential risks such as damage to fishing gear, injuries to recreational divers visiting the reef, decomposed materials or movement of the reef units off?site.

Therefore, an adequate management plan should be developed prior to the deployment of an artificial reef. The objectives of management plans are to ensure that the artificial reef is sustainably managed and that its operation does not have a significant impact on the marine environment or surrounding community. The management plan should guarantee that the commitments made in pre?planning assessments (such as environmental assessments) and any approval or licence conditions are fully implemented. These plans should clearly cover submanagement plans, research and monitoring programmes, and protocols that address any potential environmental impact identified.

The management plan should include simple actions, such as to indicate the reef location on nautical charts in order to avoid damages to fishing gear, to provide user guidelines (e.g. diver safety guidelines) to prevent injuries to people diving at the artificial reef, and to establish technical measures aimed to regulate access and exploitation at the reef site.

Physical, biological and socio?economic monitoring is a key element of the management plan as it allows assessing the structural performance of the artificial reef over time and whether the artificial reef provides the expected benefits from the ecological and environmental point of view, and evaluating the efficiency of the applied control measures.

The involvement of stakeholders in artificial reef management is crucial. Professional and recreational fishers as well as divers can provide support in reef monitoring and evaluation. Applied research is another key element in artificial reef management programmes because it provides assistance in monitoring the activities carried out at the reef, in evaluating the efficacy of the adopted management measures and, where necessary, in identifying actions to be undertaken as well as alternative management options.

Given the scarce literature concerning the management of artificial reefs, the purpose of this chapter is to propose possible management strategies for the different types of artificial reefs.

9.1. Protection artificial reefs

Generally, protection artificial reefs do not need to be subjected to any control or management measures since they act by themselves as a management tool to impede illegal trawling/dredging in sensitive habitats. Nevertheless, they would need a regular monitoring to verify their structural performance.

9.2. Restoration artificial reefs

Considering that the main purpose for the placement of this type of artificial reefs is the recovery of depleted habitats and ecosystems of ecological relevance, their access should be totally forbidden to any kind of activity, except for research, which should also monitor the physical conditions of the reef.

9.3. Production, recreational, and multipurpose artificial reefs

There is evidence that the deployment of these types of artificial reefs cannot be successful if it is not associated to site?specific management plans which regulate their exploitation (Milon, 1991; Grossman et al., 1997). Unregulated access may lead to overexploitation and to a rapid depletion of the reef resources as well as to conflicts within and between user groups. This usually happens when artificial reefs are created by public agencies in public waters without effective restrictions regarding access by different user groups (Milon, 1991) or where there is a lack of control to assure that the restrictions are respected.

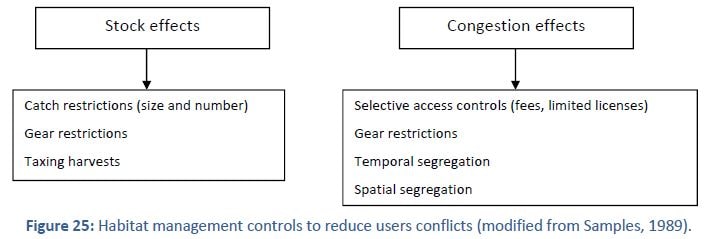

User conflicts can be generated by stock effects and congestion effects. The former may occur from overexploitation of all species or particular species at an artificial reef site. The latter occurs when the activities of different users interfere with each other and may result from either incompatible uses (e.g. recreational and commercial fishing), incompatible fishing gear or the presence of too many users in a limited site. Stock and congestion effects are not mutually exclusive (Samples, 1989).

Several basic options for artificial reef management can be identified (Fig. 25):

1) Selective access control: it may consist in the establishment of property or user rights whereby local fishers communities or recreational associations would be co?responsible with government agencies for regulating access and monitoring both the activities which are carried out at the artificial reef and the physical performance of the reef structures. It is often not feasible due to political and institutional constraints which explicitly forbid discrimination between different groups of users (Whitmarsh et al., 2008). This measure is efficiently applied in Japan, where fishers’ cooperatives are granted exclusive commercial rights to regions of the coastline, thus prohibiting other user groups from harvesting from artificial reefs (Polovina and Sakai, 1989; Simard, 1997).

2) Gear and catch restrictions: this measure aimed to orient harvesting strategies at the artificial reef through the use of selective fishing gear so to allow optimal fishing yields and avoid disruption of the natural succession of artificial reefs and associated assemblages. Exploitation strategies should include different types of fishing gear to diversify the catches and exploit all the reef resources in order to avoid alterations in the equilibrium among the functional groups of fish and macroinvertebrates inhabiting the reef. Gear restrictions have been successfully adopted to manage artificial reefs in the United States (Mcgurrin, 1989; National Marine Fisheries Service, 1990). Bag (possession) and size limits are an extensively used management tool in Australia to regulate the harvest of recreational fishers (line and spear) on natural rocky reefs and artificial reefs. The measures are regularly reviewed based on stock assessments (McPhee, 2008).

3) Temporal closure: it can be adopted to avoid the exploitation of artificial reef resources in particular seasons of the year, for example to favour the reproduction and/or the early growth of juveniles at the reef, but this measure may increase congestion and overexploitation in the remaining periods.

4) Temporal segregation of users: it is aiming at separating user groups allocating specific periods of time when each group is permitted access. Times may be chosen on the basis of various factors such as stock availability, weather conditions, market prices, etc. In this way, the different user groups can continue to use the artificial reef without interacting between them. However, this management measure is easily enforceable only when the different user groups (e.g. recreational and professional fishers) are easily distinguishable and compliance resources permit. In addition, similar to closed seasons, the reef may increase congestion within user groups because access opportunities for each of them are compressed into shorter time periods.

5) Spatial segregation of users: it consists in creating separate artificial reef sites for each user group. Nevertheless, creating and maintaining multiple artificial reefs is much more expensive than other control options and can actually increase the likelihood of conflict if perception of better catch rates on one reef over another is reported, with fishers moving without consent onto another sectors reef.

The first four options are applicable where only one reef habitat exists, while all five strategies are feasible in multiple reef site environments. Stock effects can be reduced by regulating harvesting. This can be attained by establishing selective access control, setting catch limits (size and number), limiting fishing gear and selectivity, and setting temporal catch limits (temporal closure for fishing). Congestion effects can be reduced by selective access controls, gear restrictions and temporal or spatial segregation of users.

However, no single management control can be optimal for all situations and the choice of one or more options must be based on an evaluation to determine the nature of the conflicts and the effectiveness of the management options adopted. In this case, the involvement of fishers (small?scale or recreational fishers) and/or recreational divers, as well as research in the artificial reef management, is fundamental. Based on the results of biological monitoring and on the feedback from the socio?economic data collection, it will be possible to evaluate, at regular time intervals, the effectiveness of the management measures in place and to reformulate them, if necessary, following a flexible, adaptive approach.

Figure 25: Habitat management controls to reduce users conflicts (modified from Samples, 1989).