2.7. Institutional and legal frameworks for the environmental protection of coastal lagoons

The protection of coastal wetlands, including lagoons, has become a priority objective in resource conservation policies of the Mediterranean region. Due to the multifunctional nature of lagoon ecosystems – the main uses of which are based on environmental conservation – several international intruments aimed at regulating the life of coastal lagoons in all Mediterranean countries have included preservation concerns as part of their objectives.

The first of these instruments, in chronological order, is the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat13 (1971), an intergovernmental treaty that embodies the commitments of its member countries to maintain the ecological character of wetlands and

13 Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat, Ramsar (Iran), 2 February 1971. UN Treaty Series No. 14583. As amended by the Paris Protocol, 3 December 1982, and Regina Amendments, 28 May 1987.

plan for their “wise use”14. It was adopted at an international meeting in Ramsar (Iran) on 2 February 1971, and came into force on 21 December 1975 (Ramsar web site, 2012). This convention makes explicit reference to the fact that “the landscapes and wildlife of wetlands result from complex interactions between people and nature over the centuries.”

The Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance, according to Article 2 of the treaty text, is the keystone of the Ramsar Convention. In the strategic framework’s “vision for the List”, the chief objective is in fact to “develop and maintain an international network of wetlands which are important for the conservation of global biological diversity and for sustaining human life through the maintenance of their ecosystem components, processes and benefits/services”.

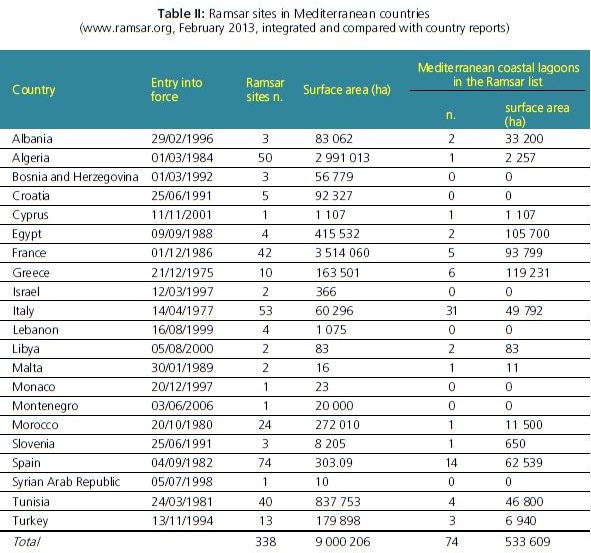

In February 2013, the Ramsar Convention had 164 Contracting Parties from all over the world, with 2 098 sites designated for the Ramsar List and a total surface area of 205 042 613 ha. Among these, 338 sites are located in the Mediterranean region, representing a total surface of 9 000 206 ha. Among Mediterranean Ramsar sites, 74 are coastal lagoons15 (21.8 percent of the total), covering a surface of 533 609 ha (Table II). In some countries, coastal lagoons are the most representative Ramsar sites, both in number and in surface. In Italy, for instance, they represent more than half of the total number of Ramsar sites in the country and about 83 percent of the total Italian Ramsar sites by surface.

Although wetlands are ecosystems that are very rich in biodiversity, their role as reservoirs of biodiversity is under siege. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment16 has found that damage to and loss of wetlands was more rapid than that of other ecosystems. As a result, species that are dependent on both freshwater and coastal wetlands are declining faster than those relying on other ecosystems.

More recently, the Birds Directive (79/409/EEC) and the Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC) have been instrumental to protection of biodiversity. The implementation at the national level of the Habitat Directive, which targets the protection of 194 threatened species and of all migratory bird species through the Natura 2000 network, has led to the identification of a number of sites of community interest (SCI) and special protection areas (SPAs) in many Mediterranean lagoon environments. SPAs are have been identified as critical for the survival of target species and form part of Natura 2000, the EU network of protected nature sites which was established in 1992. The designation of an area as a SPA enables a higher level of protection from potentially damaging developments.

Most Mediterranean countries are contracting or signatory Parties to the African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement (AEWA), which brings together 119 countries to protect 255 bird species that are ecologically dependent on wetlands for at least a part of their annual cycle (UNEP/AEWA, 2012).

14 “At the centre of the Ramsar philosophy is the “wise use” concept. The wise use of wetlands is defined as "the maintenance of their ecological character, achieved through the implementation of ecosystem approaches, within the context of sustainable development". "Wise use" therefore has at its heart the conservation and sustainable use of wetlands and their resources, for the benefit of humankind.” (from the Ramsar Convention web site)

15 “The Convention uses a broad definition of the types of wetlands covered in its mission, including lakes and rivers, swamps and marshes, wet grasslands and peatlands, oases, estuaries, deltas and tidal flats, near-shore marine areas, mangroves and coral reefs, and human-made sites such as fish ponds, rice paddies, reservoirs, and salt pans” (Ramsar Convention web site). 16 “The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, released in 2005, is an international synthesis that analyses the state of the Earth’s ecosystems and provides summaries and guidelines for decision-makers. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment assessed the consequences of ecosystem change for human well-being. From 2001 to 2005, the MA involved the work of more than 1 360 experts worldwide. Their findings provide a state-of-the-art scientific appraisal of the condition and trends in the world’s ecosystems and the services they provide, as well as the scientific basis for action to conserve and use them sustainably.” (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005).

Table II: Ramsar sites in Mediterranean countries

(www.ramsar.org, February 2013, integrated and compared with country reports) Mediterranean coastal lagoons

Another potentially important instrument for coastal lagoon management in European countries (see paragraph 2.3) is the European Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC of 23 October 2000, WFD), defined in Natura 2000 to qualitatively and quantitatively protect community waters and to establish a framework for the protection of inland surface waters, transitional waters, coastal waters and groundwater. Its main objective is to achieve a “good ecological status” for all the European waters. The Water Framework Directive (WFD) integrates the previous water legislation scattered throughout several EU directives into a common and coherent framework (Borja, 2005). The WFD brings an innovative perspective on water resources management in Europe since, for the first time, water management is mainly based upon biological and ecological aspects – such as composition, abundance of phytoplankton, aquatic flora, benthic invertebrate and fish fauna – rather than on merely physico-chemical elements, as it was previously the case with management decisions that were supposed to focus on ecosystems (Borja et al., 2004a,b; Borja, 2005). Another important feature is that many of the underlying concepts of the WFD, in particular those referring to the sustainable development of fisheries and the ecosystem approach to resources management, coincide with the ecosystem approach to fisheries (EAF), in particular as far as the ecosystem approach to the management of aquatic resources and fisheries is concerned (Cataudella and Tancioni, 2007).

Aquatic ecology scientists have been challenged by the need to put WFD principles and approaches into practice, and important experimental efforts have been deployed to monitor and preserve aquatic ecosystems. Despite the multitude of scientific papers published on the WFD, the methodological approaches proposed for its implementation and its actual application remain at present a challenge, in particular because it is difficult to define the “optimal status of an ecosystem”. However, a general and coherent classification system for all European aquatic ecosystems is still to be developed (Basset, 2010).

Aerial view of the Bages lagoon (France), photo ©H. Farrugio, 2011