6.5 Lagoon exploitation

6.5.1 Capture fisheries

Capture fisheries are present in all coastal lagoons in Italy. They are artisanal multi-species fisheries, practiced with traditional gear that require a good knowledge of the biology of the target species, such as reproduction timing, migration and seasonal or daily movements due to tides.

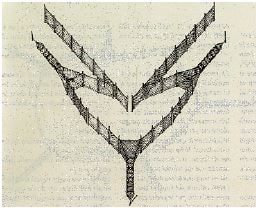

Typical instruments of lagoon artisanal fisheries are fyke nets (bertovelli) and pots, as well as nets and longlines the design, dimensions and materials of which vary according to the species to be caught and to local traditions. Indeed, the prevailing traditions of fishing and species are specific to regions and also to single lagoons. Fyke nets are used in series, with numbers and dispositions varying from a few nets to large systems, such as the giostre in Sardinia, sometimes also endowed with net walls, such as the paranze used in the lagoon of Lesina. The tresse used in the lagoon of Venice are also fixed nets, 130-140 cm tall, with a minimum mesh size of 16 mm, ending with fyke nets, locally called cogolli (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Tressa with fyke nets (cogolli), a fixed net used in the lagoon of Venice (from Provincia di Venezia, 2009)

In the lagoon of Venice, in the past, over 30 types of fishing gear were used, but generally with the evolution of techniques the variety of tools has decreased, coupled with a greater efficiency. Seines are used for the capture of sand smelts, while trammel nets and gillnets are generally used to catch mullets and seabass and seabream. The fyke nets, used for eel, gobids and other fish as well, consist of a series of capture chambers of decreasing mesh, and have dimensions, shapes and structures extremely variable from region to region and among different lagoons.

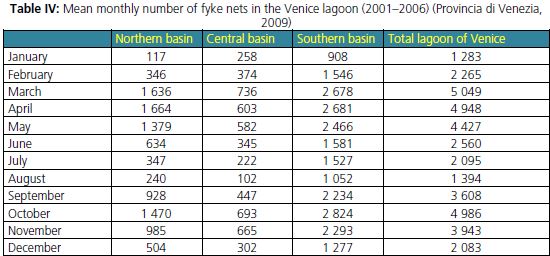

Fishing effort in terms of number of fyke nets or of fixed systems can vary within each lagoon with seasons. Just to give an idea, in the lagoon of Venice fishing is allowed all year round, but 139 the total number of fyke nets vary along the year (Table IV) from a minimum of 1 283 to about 5 000 (Provincia di Venezia, 2009).

Table IV: Mean monthly number of fyke nets in the Venice lagoon (2001–2006) (Provincia di Venezia, 2009)

On the other hand, in Sardinia, a mean number of 2 fyke nets/ha are reported in most managed ponds, and the allowed period of fyke-net fishing is 4 months (Cannas et al., 1998).

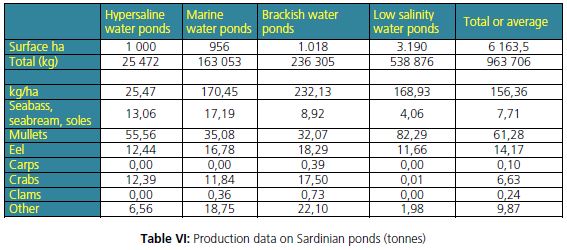

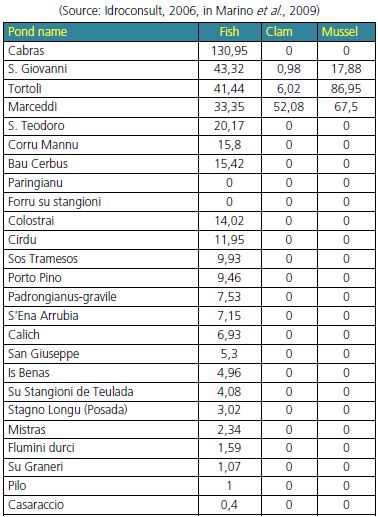

In Sardinian ponds, fyke-net and traps catches account for 24 percent of the total catch, trammel nets for 34.8 percent, harpoons for 0.28 percent and the fish barriers for 41 percent (Cannas et al., 1998). Total catch from the Sardinian ponds amounted in the 1990s to about 1 000 tonnes/year, for a mean productivity of 156 kg/ha/year (Table VI) but higher figures have been reported, up to 300 kg/ha have been estimated for these ecosystems, Marino et al., 2009), up to 600 kg/ha in some ponds, a value observed for example in the pond of Tortoli up to the 1980s. Sardinian ponds are indeed the most productive lagoons in Italy. The productivity is lower today, but remains very high when compared with that of northern Adriatic valli or other lagoons. The production greatly differs among different ponds (Table V), as a function of salinity. In the last 30 years, important dystrophic crisis occurred in some ponds in Sardinia reducing the mean annual production.

Different causes have been considered, such as: the low recruitment of the young for the increase of fishing activities along the coasts, the reduction of seawater and freshwater flows and the effect of predators such as ichthyophagous birds.

Table V: Some production data in Sardinian ponds grouped by salinity level (Cannas et al., 1998)

Table VI: Production data on Sardinian ponds (tonnes)

(Source: Idroconsult, 2006, in Marino et al., 2009)

However, reduction in productions due to a series of environmental problems affect similarly all the Italian lagoons, with the exception of a few cases. The lagoon of Orbetello, which exceeded 80 kg/ha in the 1980s, almost 50 percent of which were eels, now shows a much lower production, and catches concerns now other species such as grey mullets and seabream. The same is observed in the lagoon of Lesina. In the forties, the average output ranged between 120 and 140 kg per hectare, to drop below 60 kg in the sixties. Today the annual production averages, which consist largely of grey mullet, do not exceed 20 kg/ha.

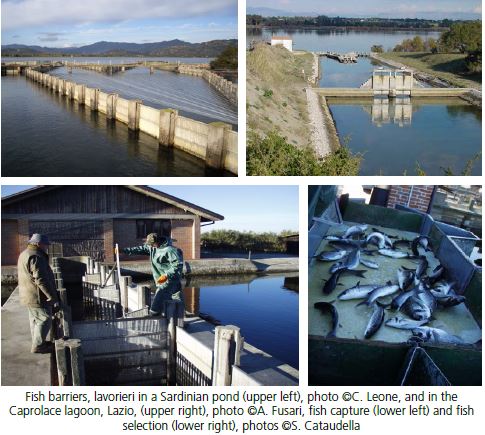

Capture fisheries in the lagoons can be exclusively based on small-scale fisheries, as in many ponds in Sardinia, or some of the Tyrrhenian coastal lakes. They can also include the use of fixed capture systems, the lavorieri. These are fixed traps, originally made of reeds and other plant materials; today most of them are made in concrete and plastic or metal grids. The design can be more or less complex, and include generally V-shaped chambers to facilitate movement of the fish towards the point of capture (Fig. 10).

Their position on the tidal channels communicating with the sea and their management allows capture of fish when they migrate from the lagoon back to the sea, during reproductive migration. In other cases, however, fish barriers can also allow the capture of fish moving from the sea towards the lagoon, as often practiced in Sardinia during summer. The dimensions of the grids of the lavoriero are such that the entry of young fish fry is always possible, in order to support fish recruitment to the lagoon.

Fish barriers, lavorieri in a Sardinian pond (upper left), photo ©C. Leone, and in the Caprolace lagoon, Lazio, (upper right), photo ©A. Fusari, fish capture (lower left) and fish selection (lower right), photos ©S. Cataudella

In some lagoons, peculiar fishing activities are carried out, related to local traditions and/or to local management strategies. Among these, two are carried out in the lagoon of Venice: the fishing for the moeche and fry fishing. The molechicoltura, i.e. the collection and production of moeche, still takes place today with the same technique unchanged from hundreds of years. The target is a stage of the crab (Carcinus mediterraneus) immediately after moulting, which is a gastronomical delicacy. The molechicoltura activity is strictly local; fishing skill has been handed down from father to son. Today it involves a limited number of employees: 60 on the island of Burano, 44 on the island of Giudecca in Venice, 108 in Chioggia.

Fry fishing is a specialist fishery that consists in collecting juvenile fish from the open lagoon at the moment of its ascent from the sea, to be used as seed for stocking in the valli (see below). This centuries-old tradition is closely linked to the development of vallicoltura. Fishers concentrate young fish, previously dispersed on the whole lagoon, in the valli that have a function of nursery areas; such valli, being distant from the sea, would not be well positioned to receive natural recruitment. Fishing for young fish is currently practiced by fishers who operate in the lagoon of Venice on a local basis, or fishers-traders moving along the Italian coasts with equipped trucks, with tanks and water oxygenation, to transport live fish. Seine nets of different lengths are used for fishing (Rossi and Franzoi, 1999).

6.5.2 Vallicoltura

The vallicoltura represents one of the oldest forms of fish culture, not only in Italy, but in the Mediterranean area, dating back at least to the eleventh century, when the practice of enclosing lagoon areas with wooden fences or reed trellises was first established. Thus, it was possible to exploit the seasonal movements of euryhaline fish fry, migrating from the sea to the lagoon where trophic and thermal conditions were optimal for their growth (Bullo, 1940; Fabris, 1991). It is only in the second half of the nineteenth century, however, that this practice became a true form of fish farming, thanks to technical hydraulic innovations and to fish culture practices (Bullo, 1899, 1940; Brunelli, 1933; Boatto and Signora, 1985).

The origin of vallicoltura can be brought about to the “nursery” role played by the lagoon for euryhaline fish species that reproduce at sea (Brunelli, 1916; Bullo, 1940; Rossi, 1986): in late winter and spring fry of seabream, seabass, plaice, sole and mullets leave the open sea to find food and protection in the lagoon shallow waters. After a period of permanence in the lagoon, young and sub-adults migrate offshore, usually during the summer and autumn months, to complete their development and reproduction. Therefore, areas of concentration of young fish were at first surrounded and enclosed with the grisiole, trellises made of reeds, to allow fish to grow exploiting the trophic resources of the lagoon, in order to catch it easily when migrating back to the sea. Along with the development of the vallicoltura, the rearing cycle was extended: fish were kept wintering in fish ponds (bacini di sverno) to be then released in the open valle in the following spring. It was thus possible to rear species that required several years to reach market sizes (Bullo, 1940; Boatto and Signora, 1985; Franzoi et al., 2002).

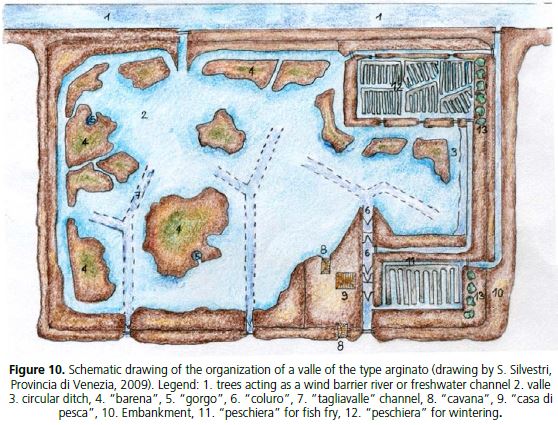

The structure of the valli has evolved over time depending both on the morphological changes that affected the lagoons, first of all the lagoon of Venice but also the other lagoons of the northern Adriatic area, and on the specialization of fishing and management techniques. The following description and terminology refers to the valli of the lagoon of Venice, but the structure and functioning of the valli is similar also in the valli of the other regions. In the past, the valli were open water spaces where exclusive fishing rights were exercised (valli aperte). The delimitation of water spaces with the grisiole gave rise to the valli a seragia; the fragile structure of these, subject to adverse weather and sea conditions, led to the reinforcement with earthen banks, originally only on a single side, in order to maintain a good water circulation (thus giving rise to a valle of the type semiarginato). The final evolutionary stage is the valle arginata, completely separated from the lagoon environment by robust long embankments, and communicating with it through sluice gates (chiaviche) that allow to control completely the water exchanges with the lagoon. This is the type of valle that currently exists in the lagoon of Venice (Fig. 10) and in the other regions as well.

Key feature of the vallicoltura is the hydraulic management of the basin that ensures a good water exchange in order to guarantee in all seasons the best conditions of temperature and salinity for fish growth and survival. The inner side of the valle is usually organized in a series of ponds or basins bordered by saltmarsh areas but communicating with each other. The valle is generally bounded by a circular ditch (fossa circondariale) following the morphology of the banks of the valle and of varying depth (between 2 and 4 meters), whose function is to facilitate the movement of water and the movement of the fish. There are also numerous channels, said tagliavalle, which are included in the main channel, which ends in the vicinity of the collection basin of the fish, called colauro, where the fish barrier, the lavoriero, is placed. Other basins are the gorghi, small deep (about 5-6 m) lakes, near the embankments, used to shelter fish in winter.

In late autumn, water level is lowered to ensure that fish concentrate in the channels. The main sluice gate is opened, and the incoming seawater spreads in all the channels system, from the main channel to the tagliavalle channels, attracting fish. Fish begin to move against the current, attracted by the warmer water at higher salinity, concentrating in the first channel, sbregavalle, and then in the colauro. Here fish are selected by the grids of the lavoriero, according to species and size, and harvested with nets if they have reached commercial size, or transferred to be wintered in the case where there are under size.

Figure 10. Schematic drawing of the organization of a valle of the type arginato (drawing by S. Silvestri, Provincia di Venezia, 2009). Legend: 1. trees acting as a wind barrier river or freshwater channel 2. valle 3. circular ditch, 4. “barena”, 5. “gorgo”, 6. “coluro”, 7. “tagliavalle” channel, 8. “cavana”, 9. “casa di pesca”, 10. Embankment, 11. “peschiera” for fish fry, 12. “peschiera” for wintering.

The vallicoltura is an extensive poly-culture method, in which the fish is free in the basin and grows exploiting natural food resources. Direct interventions on the environment are limited to the control of the hydrological regime, but also foresee stocking with young fish fry in order to sustain recruitment, and capture and selection of the fish both to protect fish from adverse conditions and predation and to obtain commercial product (Boatto and Signora, 1985; Ardizzone et al., 1988, Donati et al., 1999).

Overview of a valle of the arginato type (Valle Figheri), photo ©A. Fusari.

In the lagoons of the Venice area, in a few (five percent of the total, Neotron, 2006) valli enterprises intensive and semi-intensive basins are also present, where fish stocked at higher densities are fed, and which often are aerated to provide for the great demand for oxygen required particularly in the summer because of the higher biomass.

The main fish species cultured in the valli are seabream (Sparus aurata), seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) and the five mullet species (Liza ramada, L. aurata, L. saliens, Chelon labrosus and Mugil cephalus). To these, eel must be added (Anguilla anguilla), a migratory species linked to continental waters, lagoons included, in the growing phase of its biological cycle. A second group is represented by accessory fish species that include sand smelt, Atherina boyeri, the go, Zosterisessor ophiocephalus, the shrimps Crangon crangon and Palaemon spp. and the common crab, Carcinus aestuari.

The juveniles for restocking in the valli are from capture, or by artificial breeding. The capture is the main source of seed for all species, wild seed being preferred because better performing in the valli where conditions are similar to natural ones. Fry specialist fishery (see above) provides for this product. Stocking operations extend from March to May, but in some cases to June or, as in the case of eels, to October. The quantities per hectare are variable and amount to 150–

400 fingerlings/ha for seabass, seabream, eel and Chelon labrosus, and around 1 000/ha for other mullet fry. Stocking quantities depend on the features of the valle (extension, salinity, hydraulic conditions) and also by the main use that is mad of the valle (if largely used in other activities besides the fish, such as hunting). The availability of seed, its costs, current prices of the valle fish product, ecological factors (presence of fish predators or ichthyophagous birds, fish biomass of different fish species living in the valle are also relevant factors in planning stockings.

The productivity of the valli of the northern Adriatic is extremely variable, depending on its total surface and position, on water quality and of course on the management strategy. It is estimated that the potential productivity in the lagoon of Venice area ranges between 100 and 250 kg/ha of water surface per year (Province of Venice, 2000). In 1996, the average production of the valli in the Veneto Region (valli of the Venice lagoon and those present in the area of Caorle and Bibione), was evaluated as 132 kg per hectare of water surface (Donati et al., 1999). These values seem to confirm a substantial stability in yield values of these valli from the late nineteenth century (Bullo, 1891, 1940; Boatto and Signora, 1985, Donati et al., 1999).

For the Valli di Comacchio, in Emilia Romagna, a long time series is available, which shows a mean production per hectare in the period 1781–1982 amounting to 16.4 + 6.5 kg, with fluctuations being due mainly to adverse climatic conditions in certain years. Eel was the main species among captures, adding up to 90 percent of catches. Mean catches in the 1980s-1990s were about 15 kg/ha/year, eels about6 kg/ha.

The decrease in total yield for this complex of valli arises from the drastic reduction in surface due to reclamation. The strong decrease that has interested eel catches is anyhow to be connected to the drastic decline that eel local stocks have faced since the late 1980s across its distribution area.

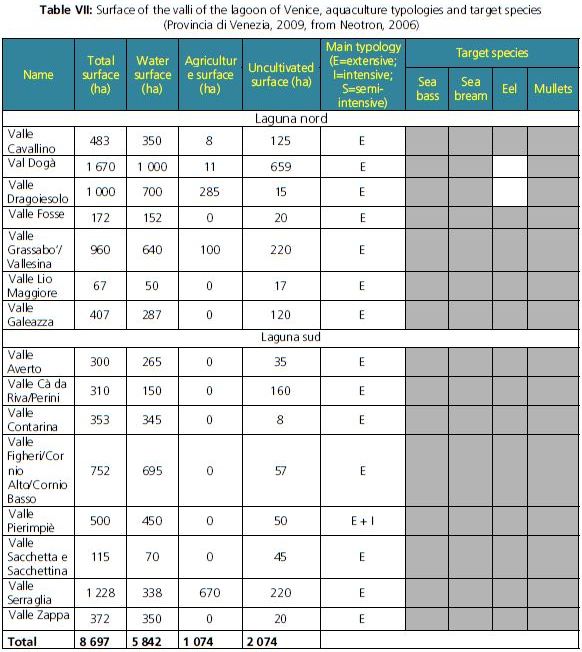

For the lagoon of Venice area, data are available about the productive valli companies that amount to 15 (Table VII). The discrepancy in number and total surface with the list reported in Table IV is due to the fact that only active enterprises are listed here, and that surface is here discriminated among water and land surface.

Table VII: Surface of the valli of the lagoon of Venice, aquaculture typologies and target species (Provincia di Venezia, 2009, from Neotron, 2006)

6.5.3 Shellfish culture

Shellfish harvesting is an important activity in Italian coastal lagoons that has now evolved towards a culture-based activity. The Manila clam production and harvesting is now the prevailing aquaculture activity in Italy, and the most important share is carried out in the lagoon of Venice. This activity, briefly described in the previous section, has created a peculiar situation in the lagoon management, and brings about a number of consequences at different levels, from the environmental to the socio-economic.

This species was introduced in the Venice lagoon in 1983; this allochthonous bivalve mollusc belongs to the same genus of the local clam Ruditapes decussatus (Linnaeus, 1758). Compared with the native species, the Manila clam proved to be more resistant to temperature changes and salinity, it can adapt to a greater variety of substrates and, most important, shows a much higher growth rate. These characteristics have led to a great success of this species, so that now

Italy, due to the almost exclusive fishing activity of the Adriatic, has the highest European production.

In the early 1990s, there were about 100 boats equipped with hydraulic dredges in the lagoon, but their use has been prohibited since 1992. The use of this tool brings about morphological changes of the bottom (Pranovi and Giovanardi, 1994), modifications of the biocenoses and short and medium-term alterations in the benthic communities. Dredges were replaced by the

rusca, now the most common method of collection, whose spreading is due to the increase of illegal fishing and the need to have a tool easy to handle even where the water is low. Other gear used for the harvest of the Manila clam are the vibrating dredge, and hand tools such as rakes and rasca, all based on the same principle to penetrate the sediment to recover bivalves.

Since the mid 1990s, Manila clam production changed from a harvest production to a culture based fishery. The Consorzio Veneto Allevamenti Lagunari has been established, which has the concession of some portions of the lagoon of Venice for the Manila clam production and harvesting; the total area in concession at present covers about 3 000 ha. The Manila clam production is now carried out by stocking wild seed (15–20 mm in size) and only rarely hatchery produced seed. Final production can reach 2.25 kg/m2, natural mortality being around 20 percent per year.

The autochthonous species Rudiapes decussates is still harvested in some ponds in Sardinia, with yields that amount to about 73 tonnes/year in Sos Tramezzos and in Marceddi (density up to 2 kg/m2). The Manila clam has been introduced also in Sardinia in some ponds, where it has superseded the autochthonous species; the maintenance and protection of the local species is of great interest in Sardinia in relation to the maintenance of biodiversity, and lower yields can be compensated by the economic return linked to an appropriate valorisation of the product.

The collection of mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) and the practices for their cultivation have been present in many Italian lagoons for a long time. In Sardinia, in several ponds (Tortoli, San Giovanni, Feraxi, Corru St'Ittiri and Corru Mannu) floating rafts (zattere) are used, rare in other regions. The most common mussel culture methods are fixed systems, longlines “monoventia” and longlines “triestino bi-triventia”. Approximately 2 000 000 longlines linear meters are available in Italy with an average of 10 000 m per farm. The regions with the highest longlines meters are Emilia-Romagna (631 150), Apulia (550 270), Veneto (303 240), Friuli- Venezia Giulia (186 440) and Sardinia (143 660).

The lagoon of Venice accounted, up to the early 1980s, for an important share of the national production (about 60 percent), with its 100 licences, and a total production of 30– 35 000 tonnes of mussels, amounting to 6 billion lire (about 3 million euros). A progressive decline in the lagoon production of mussels followed, with annual production estimated at around 21 000 tonnes in the 1980s, 9 000 tonnes in the 1990s and 4 000 tonnes inthe early 2000 (Pellizzato and Penzo, 2002; Silvestri Pellizzato, 2005). In 2005–2007, the lagoon production has declined further, with an average of 1 500–2 500 tonnes of mussels/year over a total area of 1.5 to 3 ha. This decline can be caused by several factors (Pellizzato and Penzo, 2002), that have prompted many operators to develop “offshore” mussel farms along the Venetian coast, where there is the availability of large spaces and production of mussels with highest growth rate and better quality. A change in trophic conditions of the lagoon, with a decrease in growth rates of mussels and a consequent increase in production cycle to 18 months, has been an important factor for the decline of the mussel lagoon production, as well as the increase of the risks and constraints linked to hygiene and sanitation.

6.5.4 Other harvest activities

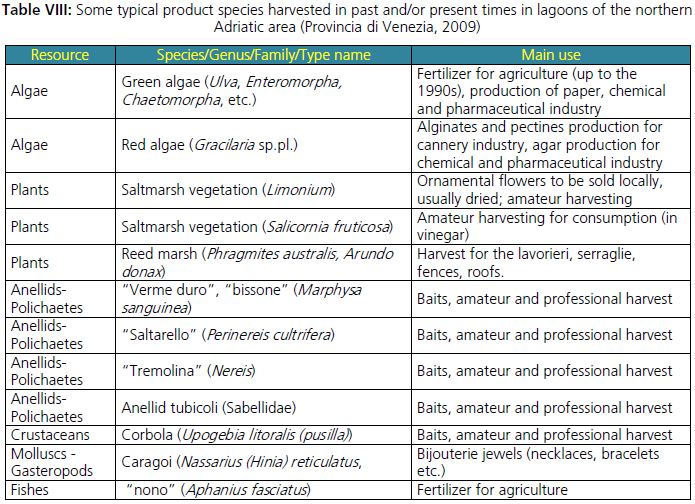

In addition to the main fishery resources, other species belonging to the flora and fauna of Italian coastal lagoons are being (or have been) exploited, albeit only occasionally or on a small scale, by fishers and other professionals or occasionally by other categories. Some of these species are not exploited but are used for food or as bait or for other uses. In Table VIII, a list of the target species of these minor harvest activities are listed, relative to the lagoons of the northern Adriatic area, but the same species have been or still are harvested in other regions of 147 Italy. These minor collection activities, practiced to supplement the family income, are currently in strong reduction. Among them is also the collection of baits, in relation to the sale for purposes of recreational fishing. The most common baits are worms (Annelid Polychaetes) as Marphysa sanguinea (muriddu), Nereis sp. (tremolina), Perinereis cultrifera. These activities, many of which are now abandoned or marginal, or even prohibited because targeting protected species, may still be an occasional source of income or supplemental to other major activities. Many of these practices, part of the traditional culture of high-Adriatic populations, common in all the fishing villages from Marano to Comacchio, have helped to maintain local identity and community folklore.

Table VIII: Some typical product species harvested in past and/or present times in lagoons of the northern Adriatic area (Provincia di Venezia, 2009)