10.5 Lagoon exploitation

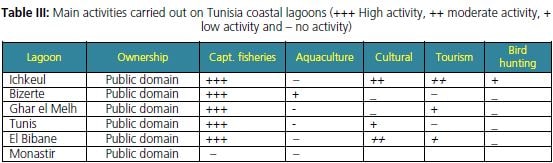

Table III: Main activities carried out on Tunisia coastal lagoons (+++ High activity, ++ moderate activity, + low activity and – no activity)

10.5.1 Aquaculture and capture fisheries

Facilities

Fishing gear

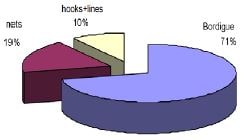

Four types of fishing gear are currently used for fish capture in the lagoons, which are the old fixed gear named bordigue (conceived and used since the nineteenth century), capetchades (“Massayda”) to fish eels, fixed nets and trammel nets, hooks and lines. For shellfish culture, mussels are reared on suspended ropes in the Bizerte lagoon. Capetchades are used in the lagoons with eels (Ichkeul, Ghar el Melh and Tunis lagoons), whereas bordigues in Ichkeul, Tunis and el Bibane lagoons represent the most productive gear with up to 70 percent of the total capture in the el Bibane lagoon. Adding to this fishing gear, Tapes decussates is being manually collected by fishers who use ancestral means in the Tunis, Bizerte and el Bibane lagoons (the technique is called “peche a pied”). The El Bibane bordigue is the longest existing fixed fishing gear in the Mediterranean (2 km over an opening lagoon-sea of 2 500 km long). Lines are used to catch fish of high commercial value such as seabass, seabream, Lichia amia and Pomatomus saltatrix, whereas the bordigue allows to catch those species plus others, especially Dilpodus annularis, annular seabream and sand streenbass. Fixed nets are used to catch Salpa salpa, mullet like species, Sparus aurata and shrimp (Penaeus kerathurus).

In the El Bibane lagoon, the capture shares of fixed gear are as follows:

71 percent with the bordigue,

19 percent with hooks and lines and

11 percent with fixed nets (Fig. 3).

El Bibane lagoon fish trap, photo ©BRL

Ingenierie IDEA Consult. 2008.

Conservation measures applying to the lagoons

are those provisions in force for artisanal fisheries.

The fishing seasons are closely linked to the

biology and trophic needs of the target fishes

(spring-winter for eels, summer for shrimp and

other times for fish species depending of their

biology).

Figure 3. Share of each fishing gear in the El Bibane lagoon

Boats

No motor boats are allowed within the lagoons in principle. The lagoon of El Bibane, however, hosts four motor boats devoted to the transport of personnel and fishing material. The fishing fleet belongs to the companies to which concessions are granted through the fisheries regional authorities. Several boats are not operating, for example in the El Bibane lagoon, five out of 20 boats fishing with hooks are immobilized (112 licences were granted in 2010 but many illegal operators are actively fishing inside and/or on the lagoon border).

The fish products are exclusively sold to the licence-holders at fixed prices communally agreed between the company and the private fishers. The issue is frequently the subject of several conflicts between the two parts.

Buildings and infrastructures

The facilities offered by the companies which are exploiting the lagoons include warehouses for gear and nets handling as well as for products conditioning and storage; those facilities exist at the Ichkeul, Bizerte, Tunis and el Bibane lagoons. In the Ghar el Melh lagoon, fishers and their cooperatives rent warehouses inside the nearby fishing port to stock fishing materials and equipments.

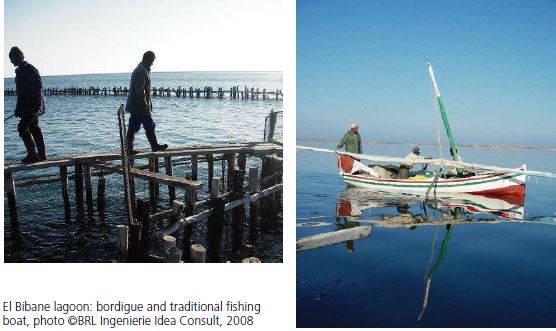

El Bibane lagoon: bordigue and traditional fishing boat, photo ©BRL Ingenierie Idea Consult, 2008

Employment and institutions

Since all the lagoons belong to the public authorities, which are acting through the Ministry of agriculture and environment (for licensing and fishing control), and also through the Agency of Environment and Agency of littoral protection and management (for lease and monitoring of the maritime water and inland space), the lagoon exploitation is used by means of licences granted to private fishers (112 licences in 2010 in the El Bibane lagoon for example) and by lease contracts to private companies. In the past, these lagoons were exclusively conceded to a public body named Office National des Peches (ONP); the latter was dissolved by the mid-1990s

and its activities transferred to the private sector.

Aquaculture and capture fisheries management

Five lagoons are of interest for fisheries and aquaculture production as well as for ecological relevance, which are ranked as follows (on the basis of their fish production in 2009):

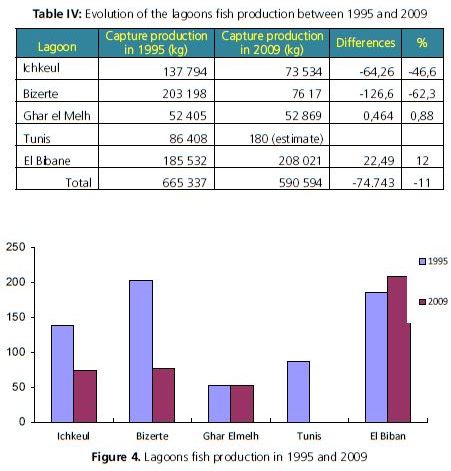

El Bibane, with about 210 tonnes in 2009 compared with 185.5 in 1995; Bizerte with 76 tonnes of fish and 200 tonnes of shellfish in 2009 compared with 203 and 130 tonnes respectively in 1995, Ichkeul with 73.5 tonnes in 2009 compared with 138 in 1995, Ghar el Melh with 53 tonnes in 2009 compared with 52.5 in 1995 and north Tunis with 85.6 tonnes in 1995. The production of the Khnis lake is insignificant; the lagoon is being used for experimentation. The whole lagoon capture production decreased from 665 tonnes in 1995 to 410.5 in 2009, i.e. 245 tonnes less (minus 38 percent in 15 years) if we do not take into account the Tunis lagoon production in 2009, for which no data are available.

Ecologically speaking, the three most interesting lagoons are Ichkeul, Bizerte and El Bibane. The first one hosts, adding to its importance for capture fisheries, a large bird population that winters inside the lagoon and in the surrounding marshes thanks to the important availability of feed. This lagoon, with a special hydrologic regime, is included within a national park that benefits of protection/conservation measures. Its environmental importance and specificity allowed classifying the park as a MAB/Unesco site, as a Ramsar wetland and as a national park by the Tunisian authorities.

The Bizerte lagoon is of interest for aquaculture, particularly shellfish (mussel and oyster) culture. Five farms are already settled on the lagoon within a limited zone of a few hectares, but larger opportunities of development exist, including for fish culture. The lagoon is potentially interesting when considering the large decontamination project that is on the way to be run, and which will allow expanding aquaculture activities

The El Bibane lagoon is interesting on account of more than one aspect since it represents the largest lagoon in the country (it yielded a fish production of about 600 tonnes/year in the past). The absence of a management plan and of relevant conservation/development measures led to the current bad situation with an average production of 250 tonnes/year. The lagoon is classified as a Ramsar site since 2007 and requires more attention.

No hatcheries exist around any of the lagoons for the moment; the activities inside the lagoons are focusing on capture fisheries, except in the Bizerte lagoon, which hosts five shellfish culture farms that are importing their fry from outside the country. There are no intensive culture ponds around the lagoons.

Restocking

The fish juveniles, especially of mullet species, are collected from the wild and restocked in the inland water bodies (dams’ reservoirs).

Selective fishery

The conservation measures are those in force for artisanal fisheries management (mesh size, number of authorized nets, minimum fish capture size, fishing zones and seasons, etc.)

Raft culture (shellfish)

In the Bizerte lagoon, mussels (on suspended ropes) and oysters are cultured. 205

Other actions to enhance productivity

Inside the Tunis lake, Ulva lactuca is regularly and mechanically removed in order to combat the proliferation of macro flora, to limit phytoplankton blooms and to improve water oxygenation. The sediment of this lagoon includes high amounts of organic matter, phosphorus and nitrogen components accumulated during many years before the restoration works.

Productions from coastal lagoons (tonnes)

The production statistics data are made available by the General Directorate of Fisheries and Aquaculture (Record books of production statistics), which is collecting those data through its representatives at the regional level. The fishery districts are acting in the global framework of the CRDA. The lagoon production data are not available in the case of the Tunis lagoon for 2009. Except the case of the El Bibane lagoon, for which time series exist from 1984, all the data are available from 1995. No processed products are reported. All the fish products are sold in fresh, except for eels, which are essentially handled alive.

The whole lagoon production decreased from 1995 to 2009, even when the estimated production of the Tunis lake (180 tonnes) is considered (Table IV and Fig. 4).

Table IV: Evolution of the lagoons fish production between 1995 and 2009

Figure 4. Lagoons fish production in 1995 and 2009

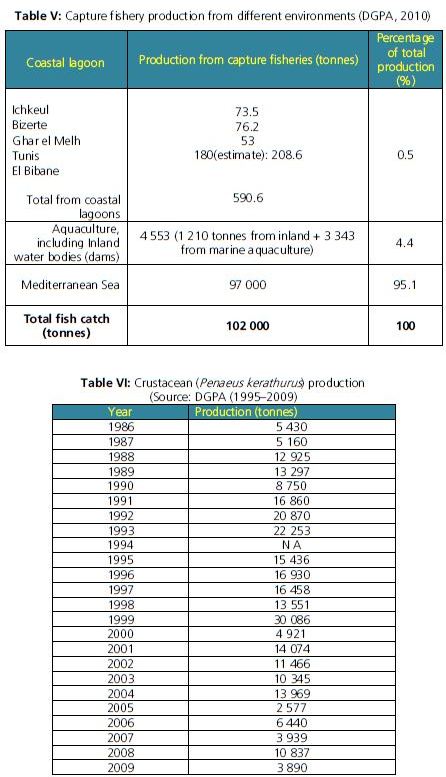

Table V: Capture fishery production from different environments (DGPA, 2010) Percentage

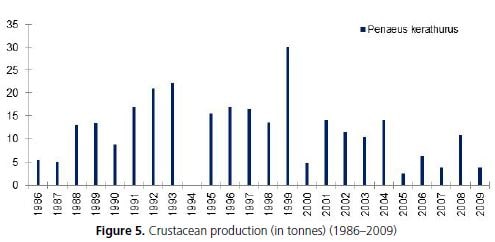

Table VI: Crustacean (Penaeus kerathurus) production

(Source: DGPA (1995–2009)

Figure 5. Crustacean production (in tonnes) (1986–2009)

The El Bibane lagoon is the main productive lagoon for shrimp, in which this crustacean is fished with fixed trammel nets. Its production is decreasing in time (Fig. 5). No culture exists for this species since the introduction of alien species is not allowed for the moment and Penaeus kerathurus (the local species) is not adapted for culture purposes, as shown by several trials.

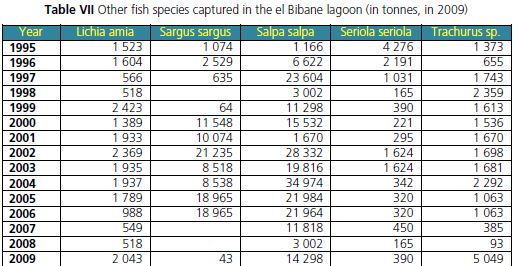

Table VII Other fish species captured in the el Bibane lagoon (in tonnes, in 2009)

Production of other species

It is strongly deemed that Ascidium-like species were harvested in the El Bibane lagoon for many years but no accurate related data are available at the relevant fisheries authority.