11.2 Generalities on coastal lagoons

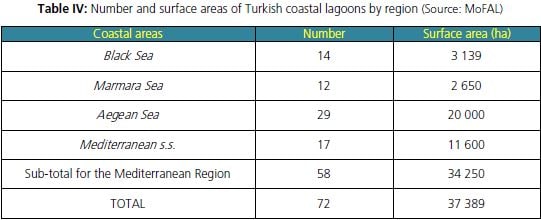

There are 72 lagoons with a total 37 389 ha surface area in Turkey, which are present along all the four coastal areas (Deniz, 2010), the Marmara Sea, the Aegean Sea and the Mediterranean Sea sensu strictu (all included in the Mediterranean Region according to the GFCM) and the Black Sea (Table IV).

Table IV: Number and surface areas of Turkish coastal lagoons by region (Source: MoFAL) Coastal areas Number Surface area (ha)

Black Sea 14 3 139

Marmara Sea 12 2 650

Aegean Sea 29 20 000

Mediterranean s.s. 17 11 600

Sub-total for the Mediterranean Region 58 34 250 TOTAL 72 37 389

Black Sea lagoons

The Black Sea is a semi-enclosed basin whose inshore waters present estuarine characteristics, significant pollution loads and high hydro dynamism. Along its southern border, salinity ranges between 16 and 18 ppt, rarely exceeding 21 ppt. Surface water temperatures show a winter minimum of around 7°C and a maximum of around 25°C in summer. Surface waters are very dynamic, with main currents flowing from west to east.

According to the nutrient levels, its waters are classified as mesotrophic. The major sources of nutrients are the disposal of Istanbul's sewage and the Danube delta, which also provide the highest loads of pollutants. Other sources of pollution are the coastal towns, whose effluents are usually pumped into the sea untreated.

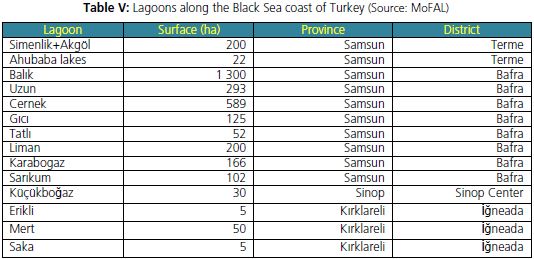

Fourteen lagoons covering a total surface of 3 139 ha are found along the Turkish side of the Black Sea (Table V). Their annual fish production is about 131 tonnes, which is almost entirely given by the lagoon complex of Bafra, where production is about 56 kg/ha.

Table V: Lagoons along the Black Sea coast of Turkey (Source: MoFAL)

Lagoon Surface (ha) Province District Simenlik+Akgol 200 Samsun Terme Ahubaba lakes 22 Samsun Terme Bal?k 1 300 Samsun Bafra Uzun 293 Samsun Bafra Cernek 589 Samsun Bafra G?c? 125 Samsun Bafra Tatl? 52 Samsun Bafra Liman 200 Samsun Bafra Karabogaz 166 Samsun Bafra Sar?kum 102 Samsun Bafra Kucukbogaz 30 Sinop Sinop Center Erikli 5 K?rklareli Igneada Mert 50 K?rklareli Igneada Saka 5 K?rklareli Igneada

The lagoons along the Black Sea coast are mainly concentrated at the large delta of the Kizilirmak River – the Bafra lagoon complex – which hosts a large wetland area that is also exploited for fishing. At present, the remaining lagoons are either abandoned or not exploited, with a fishing output resulting as negligible in the overall picture (Hollis and Thompson, 1992)

Moving from east to west, the first lagoons are the ones dotting the Yesilirmak river delta, the second and last delta of this region. Simenlik and Akgol are two interconnected stretches of water on the eastern side of the river, whereas the tiny Ahubaba lagoon complex is found on its western side. All lakes are affected by sedimentation, growing submersed vegetation cover and a lack of maintenance. Fishing management has been progressively abandoned and catches have declined greatly with respect to their importance of only relatively few years ago.

Sar?kum lagoon in the

Black Sea coast, photo

©H. Deniz

Only two lagoons of the Bafra lagoon complex still exist today: Liman and Karabogaz. The former is an isolated lake at the northernmost tip of the delta where no fishing is practised at present. The implementation of the Bafra Plain Irrigation Scheme by DSI will provide the lagoon with three sources of clean freshwater, diverting the present discharge of drainage waters from the lake to the sea. This could improve the environmental conditions of this lagoon, which is currently in danger from excessive vegetation and agrochemical inputs. Its difficult accessibility hampers a fishing exploitation and makes it a prime candidate for a wildlife sanctuary.

Karabogaz is the only lagoon along the western side of the delta. The cooperative renting it decided to ban fishing in it for three years due to the sharp decline of its catches. Its limited size and the reported absence of pressure by local inhabitants to exploit it to make a living, make it suitable for conversion into a wildlife refuge and the provision of protected-area status. The Sarikum lagoon has been a Nature Conservation Area since 1987 and the large amount of wildlife it hosts confirms that this is its most appropriate use. The remaining enclosed water areas along the coast are small lakes whose importance is restricted to recreational activities. Erikli, Saka and Mert should be included within the Wildlife Protected Area of the Demirkoy Forest, which they border.

Marmara Sea lagoons

The Sea of Marmara is a small enclosed basin linking the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea. Salinity is less than 30 ppt due to the Black Sea waters flowing from east to west. During the summer, pure seawater enters through the Dardanelles Strait.

Surface temperatures range from approximately 6°C in winter to around 24°C in summer.

Pollution and nutrients levels are increasing at an alarming rate due to the huge conurbation of Istanbul, the industrial zone of Izmit and the large holiday housing settlements along its northern and south-western coasts, together with other minor industrial centres in Bandirma, Tekirdag and Marmara.

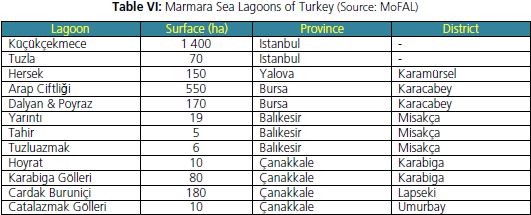

The 12 lagoons of the smallest Turkish sea add up to a water surface of about 2 650 ha (Table VI), with a negligible yearly fish catch of less than 13 tonnes, mostly produced by the lagoons of Kucukcekmece, Dalyan and Poyraz. In the latter two, the unit production is about 43 kg/ha (STM and MARA, 1997).

Table VI: Marmara Sea Lagoons of Turkey (Source: MoFAL)

Lagoon Surface (ha) Province District Kucukcekmece 1 400 Istanbul -

Tuzla 70 Istanbul -

Hersek 150 Yalova Karamursel Arap Ciftligi 550 Bursa Karacabey Dalyan & Poyraz 170 Bursa Karacabey

Yar?nt? 19 Bal?kesir Misakca Tahir 5 Bal?kesir Misakca Tuzluazmak 6 Bal?kesir Misakca Hoyrat 10 Canakkale Karabiga

Karabiga Golleri 80 Canakkale Karabiga Cardak Burunici 180 Canakkale Lapseki Catalazmak Golleri 10 Canakkale Umurbay

Once very productive and renowned for the taste of their fish, most of them are now in a critical state due to pollution and neglect (Velioglu et al., 2008).

Kucukcekmece is the largest lagoon of the Marmara but its environment is in a critical status due to the heavy pollution discharged into it by the large human settlements and the industrial areas of its catchment area.

Bucurmene lagoon in the Marmara Sea coast, photo ©H. Deniz

A group of medium-size lagoons - Tuzla, Hersek and Arapcifligi - that were once highly productive are now abandoned and being gradually filled with sediment since their connection to the sea is completely silted up.

Cardak Burunici is a coastal lagoon with full marine conditions, which could host a diversified aquaculture activity.

The other water bodies investigated are remainders of oxbow lakes (in Turkish: azmak). Their small dimensions, the difficult access and the surrounding tourist settlements that are mushrooming along the Marmara coast barely warrant the kind of rehabilitation works proposed for larger lagoons aimed at the environment and at fish production.

The feasibility plan therefore foresees the following interventions for the family-scale fishing model with limited restoration interventions could be applied only in the most favourable azmak, such as Tuzluazmak.

Aegean Sea lagoons

The Aegean coast stretches from the border with Greece southward to the Dalaman peninsula, which is conventionally used to delineate the border with the Mediterranean Sea (STM & MARA, 1997). It is an oligotrophic full strength saline sea with a complex coastline profile dotted with many islands that create complex current patterns. Salinity is typically around 38 ppt.

Due to their limited number, major rivers that flow into the Aegean have only local effects in reducing salinity in the estuarine areas.

On average, surface temperatures are higher than in the Black and Marmara Seas and increase from North to South, from around 110C in winter to around 240C in summer. Pollution and high nutrient levels occur in a limited number of places, the industrial zones of Izmir and Dalaman in particular.

Sewage inputs come from the major tourist centres and harbours and from the large holiday housing settlements.

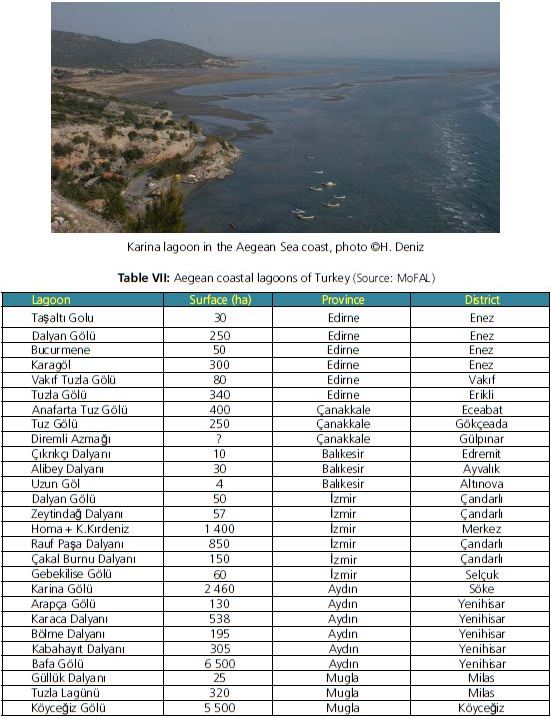

The Aegean coastline is the richest in terms of lagoon number (29), area (20 000 ha) and fish production (562 tonnes). However, two lagoons (Bafa and Koycegiz) account for 60 percent of the total area, whilst their fish production stands at 22 and 350 tonnes respectively. The latter accounts for about 40 percent of the total Turkish lagoon catch (Deniz, 2002). Both were marine gulfs during the Roman age, the huge amount of sediments caused by deforestation and subsequent erosion of the Anatolian Plain caused them to evolve into landlocked lakes. Table VII shows the Aegean lagoons (see the three photos below).

Karina lagoon in the Aegean Sea coast, photo ©H. Deniz

Table VII: Aegean coastal lagoons of Turkey (Source: MoFAL)

Lagoon Surface (ha) Province District Tasalt? Golu 30 Edirne Enez Dalyan Golu 250 Edirne Enez Bucurmene 50 Edirne Enez Karagol 300 Edirne Enez Vak?f Tuzla Golu 80 Edirne Vak?f Tuzla Golu 340 Edirne Erikli

Anafarta Tuz Golu 400 Canakkale Eceabat Tuz Golu 250 Canakkale Gokceada Diremli Azmag? ? Canakkale Gulp?nar C?kr?kc? Dalyan? 10 Bal?kesir Edremit

Alibey Dalyan? 30 Bal?kesir Ayval?k Uzun Gol 4 Bal?kesir Alt?nova Dalyan Golu 50 Izmir Candarl? Zeytindag Dalyan? 57 Izmir Candarl? Homa + K.K?rdeniz 1 400 Izmir Merkez Rauf Pasa Dalyan? 850 Izmir Candarl? Cakal Burnu Dalyan? 150 Izmir Candarl? Gebekilise Golu 60 Izmir Selcuk

Karina Golu 2 460 Ayd?n Soke Arapca Golu 130 Ayd?n Yenihisar Karaca Dalyan? 538 Ayd?n Yenihisar Bolme Dalyan? 195 Ayd?n Yenihisar Kabahay?t Dalyan? 305 Ayd?n Yenihisar Bafa Golu 6 500 Ayd?n Yenihisar Gulluk Dalyan? 25 Mugla Milas Tuzla Lagunu 320 Mugla Milas Koycegiz Golu 5 500 Mugla Koycegiz

From the national border with Greece, delineated by the River Merit, southward to Izmir, the most important is the Enez lagoon complex (Tatli, Dalyan and Bucurmene lagoons). At present, the remaining lagoons along this stretch of coastline receive little interest for exploitation for fishing and aquaculture. Most of them are abandoned and are used only for some sport fishing during the tourist season.

The lack of environmental management is rapidly isolating these environments from the sea, making them prone to sedimentation. The only exception is Anafarta Tuz lagoon, on the Gallipoli peninsula, where a Turkish company has started a project of intensive fish farming and lagoon management employing Italian expertise.

Tuzla has quite a large surface area but its output of only 4 tonnes in 1995 clearly reveals the presence of severe constraints to proper exploitation. Alibey Dalyan? is a shallow bay separated from the sea by an artificial barrier. A project for its development as a fish farm is under way. Zeytindag Dalyani, in the province of Izmir, had the same structure of embayment enclosed by fences, but it is now abandoned.

Dalyan lagoon could be an interesting – although modest-sized – lagoon environment. Unfortunately a dirt road, built right across the lagoon to reach the coastal area where very large tourist settlements are mushrooming, isolates the lagoon from any water exchange with the sea. Homa lagoon and its smaller twin Kucukkirdeniz lagoon represent a large and once productive lagoon system, which is now affected by the absence of freshwater sources.

Koycegiz lagoon on the Aegean Sea coast, photo ©H. Deniz

Rauf Pala lagoon represents an interesting example of “artificial lagoon”, which is actually a portion of the Izmir Gulf close to its northern coast and separated by an embankment equipped with fish barriers and gates. Little can be done, however, to balance the progressive impoverishment and degradation of the gulf waters, which are heavily polluted by the nearby town.

The lagoons along the delta of the Great Menderes represent one of the most interesting wetlands of Turkey. They were included in 1993 in the National Park of the Dilek peninsula under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Forestry, which is preparing a master plan for the entire area. Due to the area’s importance for fishing and wildlife and the problems that affect the whole delta, guidelines for its rehabilitation and fishing enhancement will be developed.

The Bafa lake is a brackish landlocked lake that was once an open gulf and which gave rich catches up until recently (445 tonnes in 1987). Its current very low production (22 tonnes in 1995) is directly linked to the troubled connection with the sea via the Ancient Menderes River. Since it is currently managed to avoid saltwater inflow into the plain's irrigation network, it hampers a proper stocking of the lake with adequate numbers of seed fish from the sea. The change in ownership from private hands to the government, and the ensuing new management, is reportedly a second major cause of this dramatic fall in the fishing output.

The three southernmost lagoons of the Aegean coast – Gulluk, Tuzla and Koycegiz – are all managed by fisher's co-operatives and equipped with traditional fishing installations. Koycegiz is the Turkish lagoon with the largest landings: its 350 tonnes in 1995 account for about 40 percent of total lagoon catches. Its unit production of about 64 kg/ha is also good when compared with its large surface area. The production values reported for the small Gulluk lagoon appear clearly too high to be reliable and probably represent the total landings of the cooperative, including the sea catches.

Mediterranean southern coast lagoons

The Mediterranean Sea along the Turkish coasts presents a fairly stable salinity of 39 ppt and the highest surface temperatures found in the whole Mediterranean Basin. Summer temperature is around 28°C, whereas in winter it is around 18°C. There is a small increase in the temperature averages along the coast from west to east. Like the Aegean, it is a true oligotrophic sea with the lowest productivity among the Turkish marine areas

There is a small increase in the temperature averages along the coast from west to east. Like the Aegean, it is a true oligotrophic sea with the lowest productivity among the Turkish marine areas. Industrial pollution shows a peak in the Iskenderun Bay, Icel and, to a lesser extent, Antalya, due to the discharges of their industrialized areas. Other sewage inflows also come from the major tourist centres and the proliferation of large holiday housing settlements.

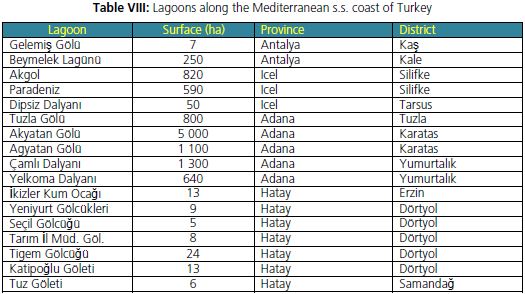

There are 17 lagoons (Table VIII), making up an area of approximately 11 600 ha, with an overall production of 183 tonnes in the Mediterranean southern coast.

Table VIII: Lagoons along the Mediterranean s.s. coast of Turkey

Lagoon Surface (ha) Province District

Gelemis Golu 7 Antalya Kas

Beymelek Lagunu 250 Antalya Kale

Akgol 820 Icel Silifke Paradeniz 590 Icel Silifke Dipsiz Dalyan? 50 Icel Tarsus Tuzla Golu 800 Adana Tuzla

Akyatan Golu 5 000 Adana Karatas Agyatan Golu 1 100 Adana Karatas Caml? Dalyan? 1 300 Adana Yumurtal?k Yelkoma Dalyan? 640 Adana Yumurtal?k Ikizler Kum Ocag? 13 Hatay Erzin

Yeniyurt Golcukleri 9 Hatay Dortyol Secil Golcugu 5 Hatay Dortyol Tar?m Il Mud. Gol. 8 Hatay Dortyol Tigem Golcugu 24 Hatay Dortyol Katipoglu Goleti 13 Hatay Dortyol Tuz Goleti 6 Hatay Samandag

The Mediterranean lagoons are mainly found in the delta areas of the only three major fluvial systems along this coastline: the Meric River, near Silifke, and the Rivers Seyhan and Ceyhan in the Cilician Plain (Deniz, 2004).

The delta of the Seyhan and Ceyhan Rivers is the last lagoon area before the national border with Syria.

The lagoons of this area stand out as among the most important of Turkey by their size, fish production potential and naturalistic interest (STM and MARA, 1997).

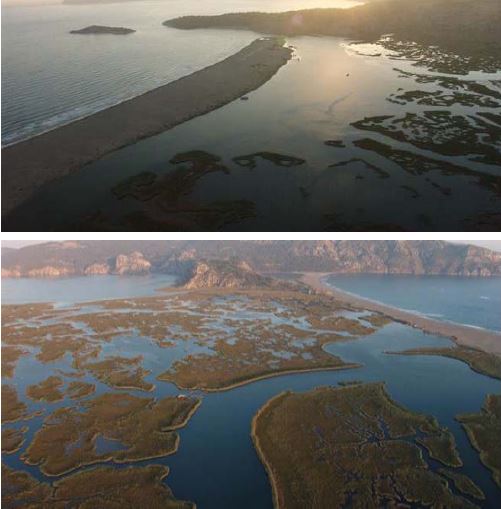

Beymelek lagoon in the Mediterranean Sea coast, photo ©H. Deniz

Main typologies

The application of the management models outlined below does not include the creation of the rehabilitation works recommended to restore or protect the lagoon environment. Their implementation is largely independent of the vocational exploitation of the lagoon and is based mainly on considerations concerning its existence, both present and future (Miller et al., 1990). The vocational management models for the Turkish lagoons are as follows:

a. environmental conservation;

b. environmental conservation plus traditional fishery ;

c. traditional fishing;

d. adapted valliculture (extensive and semi-intensive lagoon farming);

e. adapted integrated valliculture (extensive, semi-intensive and intensive aquaculture); f. recreation;

g. research;

h. education; and

i. research and education.

The lagoons of Turkey have been arranged according to their potential suitability to the above mentioned models.

Environmental conservation

This model applies to lagoons where the protection of their rich wild fauna is a priority and local inhabitants do not claim the need to exploit the environment for fishing or other uses. The waterbody is therefore managed as a wildlife reserve where the only human activities allowed should be surveillance, scientific research and education. The opportunity of giving space to ecological tourism along watched nature trails should be encouraged, provided that wildlife is not disturbed, particularly during the breeding seasons.

Environmental conservation and traditional fishery

This model applies to those lagoons where the protection of their rich wild fauna remains a priority, while at the same time there is a well-established local fishing activity that causes negligible disturbance to wildlife.

Water management should give priority to the preservation of favourable habitats for migrating and nesting birds, as well as the associated fauna and flora. The control of water level and quality of freshwater inflow requires the greatest attention to prevent alterations that would hamper the particular characteristics of these environments (Miller et al., 1990).

The traditional fishing activities practiced in these lagoon systems should be maintained and upgraded by means of low impact technologies, such as increased stocking of target fish and more selective fishing equipment. Rehabilitation interventions, if necessary, should be aimed at creating or preserving favorable environmental conditions for both the target fishing species and the natural components. The lagoons that may enter this category of management model are many water bodies to which some protection status is already granted.

Traditional fishery

Where wildlife and other natural characteristics do not endorse priority and where more sophisticated fishing management forms cannot be applied for economic reasons, traditional fishing becomes the eligible choice. Generally speaking, the creation or maintenance of a lagoon environment favourable to fish also helps the conservation of its wildlife – in some well

known cases even to excess – for instance the fish-eating birds increase with the increase in the fish population. Average production figures remain in the lower limit of the production range for lagoon environments.

The present practice could be upgraded by improving the fixed capture devices and the fish juveniles stocking management. More selective fishing practices that prevent the killing of undersize fish should be adopted. The model is a sort of simplified valliculture, mainly because a proper water management system, one of the most typical features of valliculture, cannot be implemented. The greater the control over the environment, the better the final output. Specific training is also recommended for the local fishers.

Adapted valliculture

The most advanced management of Mediterranean lagoons takes its name from the Italian word valli, which means embanked portions of a usually brackish-water lagoon.

Since the valliculture model foresees a closer control on fish and the environment than in the case of the traditional lagoon fishing, its application requires the fulfillment of more specifications that can be summarized as follows:

• The introduction of systems for a complete management of water supply and circulation by means of sluice gates, and as a consequence the modification of certain water quality parameters;

• The close control of fish migratory movements by means of hydraulic control and the operation of the fishing installation;

• The selective fishing of sizes and species by means of the fishing installations; • The stocking of live fish to overcome dangerous climatic conditions;

• The temporary stocking of seed fish of selected species under controlled environmental conditions; and

• The introduction of live organisms as integration to the natural diet of selected species.

The main diverging points from the “original” model, under the prevailing conditions in Turkish lagoons are:

• The control of seawater by means of sluice gates, since they are hardly economically justified;

• The control of freshwater by means of sluice gates, due the conflict involved with agriculture and their hard economic justification; and

• The optimization of lagoon water circulation by means of an internal network of ditches, since they are hardly economically justified.

The adoption of this tailored valliculture model requires first of all the modification of the applicable fishing legislation.

Integrated aquaculture

The rising running costs together with the decline of production have forced the extensive aquaculturists to look for alternative solutions aimed at increasing their landings.

The actions undertaken to complement extensive aquaculture (valliculture) production can be summarized as follows:

• Give priority to the farming of valuable species, mainly bass for climatic reasons, but also bream and eels, according to the practice of intensive farming in either concrete tanks or earth ponds placed in separate sectors;

• Introduce only hatchery-reared seed fish of selected species;

• Enhance the lagoon's natural productivity by discharging the effluent of the intensive sector into the waterbody;

• Introduce pre-grown fingerlings and yearlings of bream to avoid the risk of their wintering since they reach a marketable size already at the end of the first rearing season;

• Culture of new species for aquaculture, in particular extensive and semi-intensive shrimp farming in earth ponds, intensive fattening of salmon and sea trout, the latter two take place only during the cold season and use the facilities of the intensive sector that are not used at that time for bass and bream (which are wintering in dedicated facilities);

• Work the pond bottom by means of appropriate machinery to aerate and oxidize it and to release the nutrients trapped in the sediments;

• Improve the wintering facilities so that even the extreme climatic conditions that may take place – however rarely – can be faced; and

• Create semi-intensive ponds for a polyculture of selected species, usually breams and mullets.

These innovative practices could raise the production by well over 200 kg/ha, depending on the size of the intensive sector and that of the semi-intensive ponds.

Legal framework and constraints

The rich wildlife, with many species of animals and plants occurring either exclusively in Turkey or in extraordinarily high numbers, requires recognition as an important heritage of humankind deserving adequate protection. The Government of Turkey has signed several treaties by which the obligation to conserve the country's internationally important treasures of nature is confirmed. Among those international treaties that directly refer to the protection of lagoon systems, there are three particularly important ones:

• The Barcelona Convention for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea against pollution was signed by the Turkish Government in 1976. This convention includes a protocol on the establishment of SPAs, which was also signed by Turkey. The government subsequently established several protected areas, one of which is the Goksu delta.

• The Bern Convention for the Protection of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats was signed by the Turkish Government in 1984. The signatories assumed the obligation to develop national policies and appropriate plans as well as to provide the necessary training and education for the protection of those plant and animal species that are in danger of extinction. The convention compiles lists of threatened plants and animals and with the signature of the convention, Turkey agreed to protect these species and their habitats.

• The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of international importance, especially as waterfowl habitats, aims to prevent actions that could lead to the loss of wetlands. Wetlands contribute significantly to the balance of the water regime, provide shelter for plants and animals, especially for water birds, and constitute a substantial economic, cultural, scientific and recreational resource. Turkey became a party to this convention in 1994 and subsequently designated five areas to be covered by the convention. These areas include the Goksu delta.

The Turkish Government has not only expressed its will to conserve nature by signing the above conventions, it also implements them on a national level and takes actively part in the international discussion process. In addition, the Turkish Government furthers conservation issues on other international levels, e.g. by being a party to the World Heritage Convention of Unesco. However, its signature is still lacking under the Convention on Biological Diversity, which emphasises the need for protection and utilisation of biological diversity and the equitable sharing of profits made by its utilisation.

There are six types of protection status concerning lagoons in Turkey.

National parks

• Dilek peninsula and Menderes delta national park. Park since 1966, in 1993 it includes the Menderes delta area. Main lagoons: Karina Golu, Mavi Golu, Kara Gol

• Gelibolu peninsula national park. One lagoon: Anafarta Golu

Specially protected areas

• Goksu delta. It includes the lagoons of Akgol and Paradeniz; total area 4 350 ha; declared on 2/3/1990; incorporated in the list of Ramsar Treaty on l7 May 1994.

• Koycegiz lake and lagoon. It includes the lagoon of Gelemis Golu; total area 19 000 ha; declared on 18 January 1990.

Natural parks

• Bafa lagoon; declared on 8 July 1994.

Nature conservation areas

• Yumurtal?k Golu: declared on 8 July 1994; total protected area: 16 430 ha. • Sar?kum Golu: declared 30 July 1987; total protected area: 785 ha.

Wildlife conservation areas

• K?z?l?rmak delta (Samsun): declared Site for the Preservation and Reproduction of Waterfowl on 1979; it includes Cernek Golu; protected area: 13 125 ha.

• Simenlik lagoon (Terme): declared Site for the Preservation and Reproduction of Waterfowl on 1975; protected area: 16 043 ha.

• Homa lagoon (Izmir): declared Site for the Preservation and Reproduction of Waterfowl on 1980; it comprises Homa lagoon and Camalt? Salt Marshes (Camalt? Tuzlas?); protected area: 8 000 ha.

• Akyatan lagoon (Adana): declared Site for the Preservation and Reproduction of Waterfowl on 1987; protected area: 7 500 ha.

• Gokceada (Canakkale): declared on 1988; protected area: 28 204 ha.

224

• Seyhan River and Tuz lagoon (Adana): declared Site for the Preservation and Reproduction of Waterfowl on 28 December 1995; protected area: 5 796 ha.

Site Areas of the Regional Councils for the Protection and Control of Natural and Cultural Heritage

• K?z?l?rmak delta (Samsun): decision No.1908/21 April 1994

• Sar?kum lagoon (Sinop): decision No. 1198/21 November 1991

• Dalyan, Is?k and Tasalt? lagoons, (Edirne, Enez): decision No.2232/17 March 1995 • Karagol lagoon (Edirne, Enez), decision No.1908/7 February 1992

• Tuzla lagoon (Edirne, Kesan): decision No.1733/10 February 1994

• Poyrazlar lagoon (Sakarya, Adapazar?): decision No.2916/16 January1993 • Hoyrat Golu (Canakkale, Biga): decision No.2211/13 January 1995

• Cardak lagoon (Canakkale, Cardak): decision No.2441/27 May 1995

• Candarl?, Dalyan lagoon (Izmir, Dikli): decision No.4274/10 March 1993 • Dalyan (Mugla, Koycegiz): decisions No.3722/27 March 1990; 2342/15 November 1994

• Gelemis lagoon (Antalya, Kas): decision No.719/20 June 1987; 1273/14 April 1990 and 4933/17 June 1995

• Yumurtal?k lagoon (Adana, Yumurtal?k): decision No.1609/19 November 1993