11.5 Lagoon exploitation

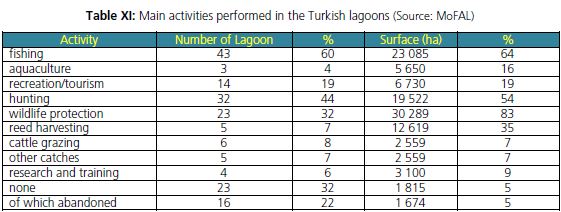

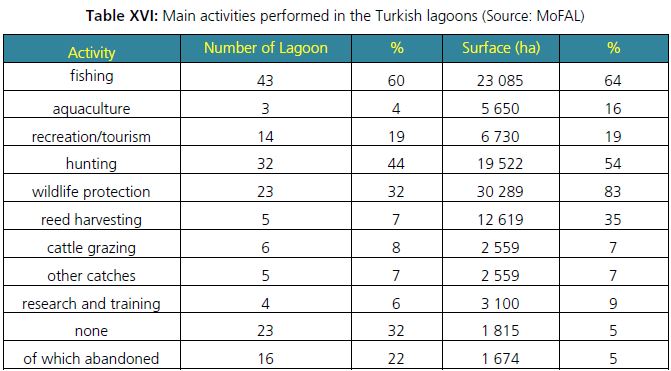

Turkish lagoons are used for many purposes and the following criteria were established for classification by MoFAL (1997): fishing, aquaculture, recreational, tourism, hunting, wildlife protection, reed harvesting, cattle grazing, leech collection, research and training, none, previously exploited, and “but currently abandoned” (Table XI).

Table XI: Main activities performed in the Turkish lagoons (Source: MoFAL)

Activity Number of Lagoon % Surface (ha) % fishing 43 60 23 085 64 aquaculture 3 4 5 650 16 recreation/tourism 14 19 6 730 19 hunting 32 44 19 522 54 wildlife protection 23 32 30 289 83 reed harvesting 5 7 12 619 35 cattle grazing 6 8 2 559 7 other catches 5 7 2 559 7

research and training 4 6 3 100 9 none 23 32 1 815 5 of which abandoned 16 22 1 674 5

The main activity is traditional fishing, which is carried out in 43 lagoons, representing 64 percent of the total surface. Different types of nature and wildlife protection have been declared for an outstanding 83 percent of the lagoon surface, amounting to 23 water bodies. However, the ban on this activity in protected areas is not fully enforced.

11.5.1 Aquaculture and capture fisheries

Facilities

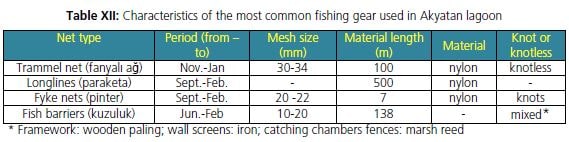

Fishing gear: The most common fishing gear is trammel net, longlines, fyke nets, knots and fish barriers. In Table XII are given the most common fishing gear used in the Akyatan lagoon.

Table XII: Characteristics of the most common fishing gear used in Akyatan lagoon

Net type Period (from – to)

Mesh size (mm)

Material length

(m) Material Knot or knotless

Trammel net (fanyal? ag) Nov.-Jan 30-34 100 nylon knotless Longlines (paraketa) Sept.-Feb. - 500 nylon - Fyke nets (pinter) Sept.-Feb. 20 -22 7 nylon knots Fish barriers (kuzuluk) Jun.-Feb 10-20 138 - mixed* * Framework: wooden paling; wall screens: iron; catching chambers fences: marsh reed

Boats: Boats in Turkish lagoons are mainly fiberglass-lined wooden barges. No engines are allowed during the fish catch, but sometimes motor-boats are used to tow the barges to the fishing areas when they are too far from the landing site. Distribution of boats is done according to the gear on board: the “kucuk mavna” are used for all kind of fishery into the lagoon whilst the “buyuk mavna” are used only for fish collection from the fish barrier and its transport to the landing site.

Other facilities: There is only one hatchery in the Beymelek lagoon, operated by the Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Livestock.

Work force, establishments and institution

Fishers come from the villages surrounding the lagoon.

In addition to fishery co-operatives, fishery cooperative associations, the Central Associations of Fishery Cooperatives (SUR-KOOP) and Central and Regional Fishery Advisory Committees have an important role to play as representative stakeholder organizations. Currently there are 490 fisheries cooperatives as recognised under the Fisheries Cooperative Law 1163, with a total membership of 24 920; note that a coop can be established as long as there are at least seven signatories to the memorandum of incorporation.

A minimum of seven or more cooperatives that have the same objectives can establish a central union. There are 13 regional unions of fisheries cooperatives within Turkey, comprised of reportedly 482 cooperatives and one central union in Ankara.

Lagoons are mainly operated by cooperatives, except in a few lagoons. The Turkish Fisheries Law gives priority to fisheries cooperatives in lagoons.

Aquaculture and capture fisheries management

The same model of traditional fishery management is currently adopted by almost all Turkish lagoons where this activity is still present. The only notable exceptions are the lagoons of the Kizilirmak delta, where the need to keep their freshwater characteristics does not allow the adoption of permanent passes and the use of a fixed fishing trap (STM and MARA, 1997). Lagoon fisheries are usually managed as follows: from June to January, the fishers trap the fish inside the lagoon by dosing the fishing barrier – a fixed trap usually made of a paling framework and marsh reed and fences placed at the lagoon mouths to the sea. The fishers do this when they believe that enough fish have entered the lagoon, then catching the fish trapped in commences immediately after the closure of the barrier.

Fish barrier in the Koycegiz lagoon, photo ©H. Deniz

Beside the fishing barrier, different kinds of stationary or moving nets may also be employed to make catching quicker and more complete. Inside the lagoon, fishers mainly use stationary gear such as trammel nets, longlines and fyke nets.

From an ecological point of view, the lagoon fish stock is an exclusive function of the following factors: natural recruitment and the lagoon's natural capacity to entrain and retain the colonizing stages that immigrate.

To summarize, this management scheme exploits the lagoon as a mere fishing trap, representing merely a basic level of lagoon exploitation for fishing purposes. By definition and for the considerations given below, this practice involves several constraints to the optimal use of the lagoon environment and its fish resources.

The traditional structure has several limits hampering its present functionality. As it stands, it will not be able to meet any increased fish production resulting from possible improvement measures (STM and MARA, 1997):

• The structure as a whole is poorly selective, allowing the capture of undersized fish;

• Its maintenance costs are high in terms of workforce and materials, which should be replaced every year;

• The total fish holding capacity of the standard fishing chamber is less than 10 m2 since the largest part of it is taken up by a deep V-shaped slide entrance for fish, which frequently forces the fishers to fish in overcrowded conditions;

• The reed fences are not a suitable barrier against the blue crabs, which enter the capture chamber and eat the fish trapped inside, which cannot escape attack;

• Its home-made construction does not make the “kuzuluk” a suitable tool for catching eels due to their ability to escape loose barriers; and

• The walls of the capture chambers are made of reed fences and rusty iron grids with rough surfaces which may damage fish skin after prolonged stocking, thereby reducing their commercial value.

Moreover, current regulations on the use of the fishing installation do not really engender a strict control of fish flows into and out of the lagoon, for the following main reasons:

• When the barrier is open, juveniles can enter the lagoon and adult fish can return to the sea;

• There are no special side entrances to allow fingerlings to move towards the lagoon; and

• There are no enclosures for the temporary stocking of undersized fish that become trapped in the fishing installation that are not suitable for the market.

Artificial propagation

The hatchery in the Beymelek lagoon operated by the Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Livestock has a 20 million fry production capacity. The main species are seabass and seabream.

No other actions to enhance productivity (pre-fattening, artificial nursery areas, restocking, intensive aquaculture, predator control, selective fishery, wintering strategies and seaweeds control) are present in Turkish lagoons.

Productions from Turkish coastal lagoons

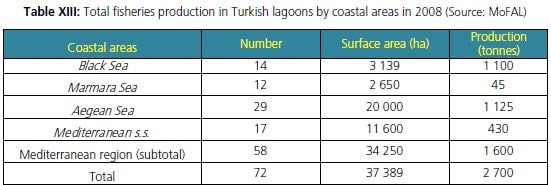

The total 2008 fisheries productions for Turkish coastal lagoons added up to 1 600 tonnes for the Mediterranean Sea and to 1 100 tonnes for the Black Sea (Table XIII). Single annual productions are available for Akyatan lagoon (1986–2008) and for Koycegiz lagoon (1978– 2008).

Table XIII: Total fisheries production in Turkish lagoons by coastal areas in 2008 (Source: MoFAL) Coastal areas Number Surface area (ha)

Production

(tonnes)

Black Sea 14 3 139 1 100 Marmara Sea 12 2 650 45 Aegean Sea 29 20 000 1 125

Mediterranean s.s. 17 11 600 430 Mediterranean region (subtotal) 58 34 250 1 600 Total 72 37 389 2 700

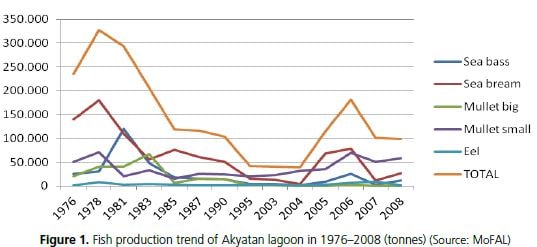

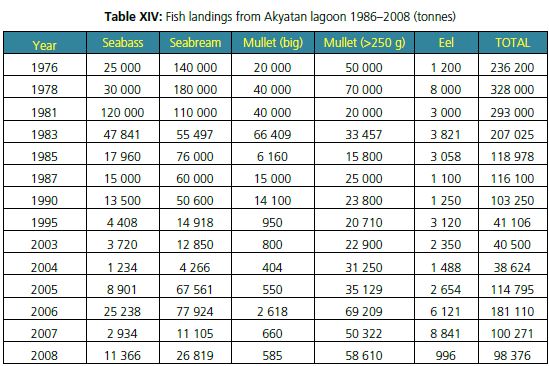

Akyatan lagoon: According to the catch figures made available by the tenant, total catches of all species have decreased since 1978, with the exception of 2008. The blue crab, once a relatively valuable product of the lagoon, is at present of no value. A blue crab canning factory close to Karatas closed its business activities, which are otherwise highly successful, because of the excessive rent costs requested by the municipality.

Fish catches have been dominated by seabream and seabass over the past 20 years. Seabream increased its relative catch by more than 15 percent from 1978 to 1995, whilst declining in overall weight from 180 to 15 tonnes. Seabass showed a similar trend, increasing from 9 percent of the catch in 1978 to 19 percent in 2008. Eel catches have increased more than fivefold in relative importance in the same years, but total figures decreased from 8 tonnes in 1978 to 3 tonnes Akyatan lagoon: According to the catch figures made available by the tenant, total catches of all species have decreased since 1978, with the exception of 2008. The blue crab, once a relatively valuable product of the lagoon, is at present of no value. A blue crab canning factory close to Karatas closed its business activities, which are otherwise highly successful, because of the excessive rent costs requested by the municipality.

Mullet are commonly separated into two size groups: large grey mullet (M. cephalus, local name “kefal”) and mullet lighter than 250 g (local name: “tubara”). In the latter, all the mullet species common in the area are included. The overall mullet catch plummeted from 110 tonnes in 1978 to 31 tonnes in 2008 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Fish production trend of Akyatan lagoon in 1976–2008 (tonnes) (Source: MoFAL)

To evaluate the lagoon's productivity, calculations have been made considering a permanent water-covered area of 5 000 ha. Productivity was highest in 1978 with 65 kg/ha, whilst current productivity is only 4.6 kg/ha.

Table XIV: Fish landings from Akyatan lagoon 1986–2008 (tonnes)

Year Seabass Seabream Mullet (big) Mullet (>250 g) Eel TOTAL 1976 25 000 140 000 20 000 50 000 1 200 236 200 1978 30 000 180 000 40 000 70 000 8 000 328 000 1981 120 000 110 000 40 000 20 000 3 000 293 000 1983 47 841 55 497 66 409 33 457 3 821 207 025 1985 17 960 76 000 6 160 15 800 3 058 118 978 1987 15 000 60 000 15 000 25 000 1 100 116 100 1990 13 500 50 600 14 100 23 800 1 250 103 250 1995 4 408 14 918 950 20 710 3 120 41 106

2003 3 720 12 850 800 22 900 2 350 40 500 2004 1 234 4 266 404 31 250 1 488 38 624 2005 8 901 67 561 550 35 129 2 654 114 795 2006 25 238 77 924 2 618 69 209 6 121 181 110 2007 2 934 11 105 660 50 322 8 841 100 271 2008 11 366 26 819 585 58 610 996 98 376

Total production has progressively decreased and shows an evident negative trend since 1978, with the only exception being the year 2008. Some figures of previous years given by the renter cast even more evidence on the fishery decline when compared with the period 1986–2008 (Table XIV).

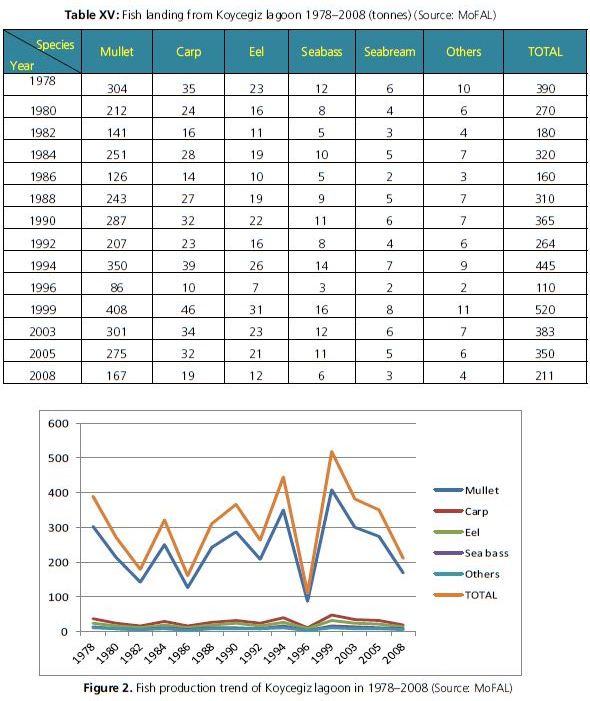

Koycegiz lagoon: According to the catch figures made available by the tenant, total catches of all species have decreased since 1978, with the exception of 2008. Fish catches have been dominated by mullet, eel and seabass over the past 20 years. Mullet is in the front rank with 209 tonnes (78.4 percent) and carp with 23 tonnes (8.8 percent), eel with 15 tonnes (5.9 percent ), seabass with 8 tonnes (3 percent) and seabream with 4 tonnes (1.6 percent) are fallow mullet in Koycegiz lagoon complex. Production of other fish amounts to 4 tonnes (2.2 percent). The biggest portion of mullet belongs to Mugil cephalus with market value and egg roe.

The Koycegiz lagoon Complex has an integrated management system. There are 34 fish barriers and five fish traps with eight inner courts which are used for fishing activities. Fish production changed from 109 tonnes in the last two decades to 520 tonnes in 2008. Average production is 265 tonnes in the last 20 years. Average fish production per ha was 48 kg (20–81 kg) in the past decade (Table XV, Fig. 2).

Table XV: Fish landing from Koycegiz lagoon 1978–2008 (tonnes) (Source: MoFAL)

Figure 2. Fish production trend of Koycegiz lagoon in 1978–2008 (Source: MoFAL) 234

11.5.2 Other uses

Recreational activities

In addition to fishing activities, there are also other activities such as recreation, hunting, wildlife protection, reed harvesting etc. (Table XVI).

Table XVI: Main activities performed in the Turkish lagoons (Source: MoFAL)

Activity Number of Lagoon % Surface (ha) % fishing 43 60 23 085 64 aquaculture 3 4 5 650 16 recreation/tourism 14 19 6 730 19 hunting 32 44 19 522 54 wildlife protection 23 32 30 289 83 reed harvesting 5 7 12 619 35 cattle grazing 6 8 2 559 7

other catches 5 7 2 559 7 research and training 4 6 3 100 9 none 23 32 1 815 5 of which abandoned 16 22 1 674 5