CASE STUDY 4. TOWARDS A STOCK-WIDE ASSESSMENT OF THE EUROPEAN EEL: STATUS OF THE ADVICE AND OF THE MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK IN EUROPE, AND EVIDENCE FOR THE NEED OF A CONTRIBUTION FROM THE MEDITERRANEAN AREA

E. Ciccotti*, R. Poole**

*Universita Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy

**Marine Institute, Newport, Ireland

Introduction

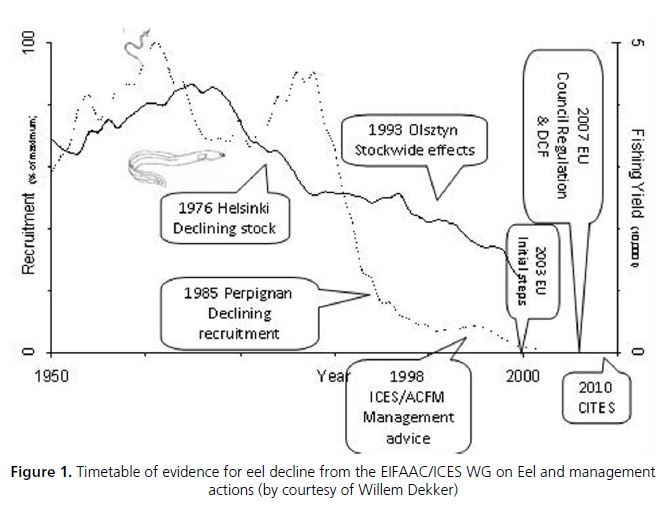

Concern about the conservation of the European eel, Anguilla anguilla, has been growing in the course of the last two decades, and the need for conservation and management measures was clearly identified by scientists, managers, and even by the public opinion. For this species in fact major problems exist, in relation to a continent-wide decline in recruitment observed since the late 1980s, and to a contraction in adult eel capture fisheries (ICES, 2001; Dekker, 2002). If compared with other shared species or to other migratory fish, the eel shows some peculiar features. Eel exploitation occurs exclusively within national boundaries, in continental waters, without any interaction between economic zones, typical eel fisheries being mainly small-scale. The spawning process takes place in international waters, and all oceanic life stages are unexploited. Finally, the population is panmictic and the species is a shared resource by practically all European and Mediterranean countries.

The unique status of the eel was defined in 1976, when a joint International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES)/EIFAC Working Party on Eels was established, which has met in alternate years since then. Within the WP, a coordinated monitoring for eel recruitment was set up, that allowed to document and follow the decline of supply following the abundance of the 1970s (Moriarty, 1990; 1996). The EC, in 1997, requested ICES to provide information about the status of the eel, in order to ensure a sustainable development of eel fisheries within the European Union, and in 1998, having acknowledged that eel stocks were outside safe biological limits, has requested to provide escapement targets and other biological reference points. The general concern by fishers, fish culturists and scientists alike on the decline in recruitment and fishery yields of the eel led to a strong debate and numerous consultations.

With specific reference to the Mediterranean, in 2002 a STECF Subgroup on Mediterranean included the eel within the species for which a scientific evaluation and critical review of the background information were performed, in consideration of the fact that this resource is shared among the majority of Mediterranean countries. Eel, in fact, is included among the shared stocks in the Community Action Plan for the conservation and sustainable exploitation of fisheries resources in the Mediterranean Sea under the Common Fisheries Policy (COM(2002)535).

In October 2002, the ICES pointed out the urgent need for a recovery plan for European eel that should include measures to reduce exploitation of all life stages and restore habitats.

Management actions

The strong need for urgent management actions has since been acknowledged, also supported by the precautionary principle, which suggests that high-risk situations need urgent protective measures. After a long process, which foresaw consultations at many levels with all stakeholders, in 2007 Regulation 1100 has been issued by the EU, aimed at the recovery of the European eel stock. In conservation terms, the main objective of eel management actions is identified in allowing an adequate escapement of silver eels. A specific level of escapement has been indicated in the Regulation, corresponding to 40 percent of the pristine escapement level. This is, therefore, the target that each EU Member State has to consider. In taking into account the possible management measures and the rebuilding plan targets, the overall approach of the document is centred on ICES advice. In many areas, the quickest and most effective measure to increase the survival of eel will prove to be a reduction in fishing, whereas environmental improvements may take some years to show results. A number of actions are identified, which are intended to develop a comprehensive basis for rebuilding eel stocks, based on locally appropriate actions and targets. Another important step for eel protection has been the inclusion in 2008 of eel in Annex IV of CITES, which regulates its trade.

In 2008, all EU Member States submitted eel management plans (EMPs), and in 2009 all plans were evaluated by the ICES, modified accordingly and approved. At present, EMPs are being implemented in all participating countries, and a first report to the EU is foreseen in 2012. The 2012 reports shall provide ICES with the tools to proceed to a stock-wide assessment for eel, to which new actions shall follow depending on the outcomes of the assessment. In fact, the Commission should present to the European Parliament and Council, not later than 31 December 2013, a report with a statistical and scientific evaluation of the outcome of the implementation of the eel management plans.

Figure 1. Timetable of evidence for eel decline from the EIFAAC/ICES WG on Eel and management actions (by courtesy of Willem Dekker)

Role of the European Inland Fisheries and Aquaculture Advisory Commission (EIFAAC)/ICES Working Group on Eels

The EIFAAC/ICES Working Group on Eels since 1975 has had an important role in providing scientific and technical background information on eel.

The WG evolved in time from a group organising symposia on eel biology to a technical working group dealing with data collection and evaluation, assessing trends, dealing with methodological issues, stock-wide dimension, quality issues, effects of anthropogenic impacts and global changes, suggestions for a recovery plan. The Eel Working Group is now the expert group providing background for advice, and a series of thematic Workshops are taking place to evaluate data and methods that will feed into the stockwide assessment of the European eel.

In order to assess whether the measures being applied under the Regulation are adequate to halt the decline and create a recovery, it is in fact necessary to have a complete assessment of the stock over the whole geographic range.

CITES regulates the import/export of eels from EU territory and from individual non-EU countries, by means of a requirement for a so-called “non-detriment finding” (NDF). Minimal conditions for a NDF are that the import/export is “not detrimental to the survival of the species” and “that species is maintained throughout its range at a level consistent with its role in the ecosystems in which it occurs”. Due to the panmixia of the eel (i.e. local silver eel production contributes an unknown fraction to the entire European eel spawning stock, which in turn generates new glass eel recruitment), the efficacy of local protective actions (e.g. single EMPs, national export regulation) cannot be post-evaluated without considering the overall efficacy of all protective measures taken throughout the distribution range.

All this requires an international post-evaluation. There are two different approaches for this, a centralised assessment, or a regional stock assessment and post hoc summing up of indicators for total stock assessment. The second appears to be more pragmatic and to relate more directly to the approach taken in the EU Eel Regulation and CITES procedures. For quality control, however, even a regionalised assessment will require that data are made available.

The stock-wide assessment

Among the actions propedeutical to the stock-wide evaluation of the European eel foreseen in 2012, a specific study group intended to design, test, analyse and report on a method of scientific ex-post evaluation at the stock-wide level of applied management measure for eel restoration was set up (ICES Study Group on International Post evaluation on Eels, SGIPEE).

The objective of eel stock assessment is to quantify the biomass of silver eel escaping, in order to assess compliance with the EU target of 40 percent of pristine biomass without anthropogenic mortality. Given that it will be impractical to directly assess silver eel biomass and mortality in many rivers, yellow eel stock assessment will also be required.

Scientific reference points have not been previously set for eel. The EU Regulation sets a long term escapement objective for the biomass of silver eel escaping from each management area at 40 percent of the pristine biomass (B0) or Blim. However, no explicit limit on anthropogenic impacts Alim was specified, even though current biomass is (far) below B0 and Blim. The biomass reference point of Blim = 40 percent of B0 corresponds to a lifetime mortality limit of ?Alim = 0.92, unless strong density-dependence applies. As an initial option, it has been recommended to set BMSY-trigger (value that should trigger a mortality reduction) at Blim, and to reduce the mortality target below BMSY-trigger correspondingly. Allowing for natural variation in B0 and for uncertainty in the estimates of status indicators and reference points, the resulting reference points (Blim, BMSY-trigger and Alim) should be considered as somewhat optimistic or unsafe. Noting the relationship between biomass stock reference points Bcurrent, BMSY-trigger and mortality reference point ?Alim, the actual value for ?Alim below BMSY-trigger must be determined on a country (or Eel Management Unit) basis.

On the basis of these considerations, the minimum data requirements for the post-evaluation are therefore B0, Bbest, Bpost and ?A (“3Bs&A”). All those countries that implemented EMPs in the 2009–2011 reviewed these estimates in 2012 and reported these reviews to the European Commission. Ideally for the post-evaluation of the Regulation, therefore, these B and A estimates should be provided in these reviews, and reported either at the country level and/or disaggregated at the EMU or catchment level. Furthermore, there are some countries in the EU who have not implemented EMPs, and there are a number of countries outside the EU that have an eel production but are not subject to the Eel Regulation. The potential implications of this scenario should be considered. On the whole, 38 countries are comprised within the eel distribution area including Europe, Africa and Asia and have presently (or have had in the past) eel capture fisheries production according to FAO Fishstat (2011). Of these, only 19 countries are in the EU and have produced EMPs (SGIPEE, 2011).

The European Eel Regulation recognises that cooperation between countries within and outside EU is desired, especially where management measures taken in one country might interact with measures taken in other countries. This has brought attention to the fact that the “missing” countries that are most relevant to the production assessment are the Mediterranean countries. The Mediterranean area has been neglected up to now regarding its role in the stock-wide assessment. A distinctive contribution regarding potential and actual escapement for Mediterranean areas might be envisaged, on the basis of specific growth patterns, silvering rates and sex-ratios (Bevacqua et al., 2006).

The need to involve Mediterranean countries

The need for a contribution of the Mediterranean area appears therefore suitable and urgent, because a stock-wide evaluation needs to be comprehensively addressed to the whole eel distribution area. Some distinctive features of exploitation, in particular with regards to Mediterranean coastal lagoons, provide a key to the setting up of a relevant geographical management unit (Ciccotti, 2005). In this sense, the example of the Baltic area can be of interest, where a specific group has been organised to deal with this shared resource, aiming at carrying out a joint analysis and an efficient assessment of the local stock, also quantifying interactions.

The first approach is therefore to enhance knowledge and participation of Mediterranean countries, also increasing coordination and communication. An initial step was represented by the “Transversal expert meeting on European Eel” that was held in Sfax, Tunisia, September 23– 24, 2010, within the GFCM meetings. This meeting dealt with the involvement of some northern African countries in eel, particularly Tunisia. The interest and urgency to be strongly involved in the restoration of resources of this species and the need to establish a regional coordination was clear.

A possible strategy could be to organise a thematic workshop by 2013. This workshops could address: a) initial planning, data inventory, data collation (eel and its habitat in the Mediterranean), assessments and initial analysis, b) recruitment, yellow eels stocks, silver eel, fisheries and other impacts (e.g. hydropower, aquaculture, cormorants), stock surveys and data collection, c) stock assessment, the ICES framework of 3Bs&A (as worded in the EU reporting template), the overlap and interactions between countries, d) dissemination and communication of the results to the managers and stakeholders, placing the results out at a local level and also in the wider stock context. This will allow for a broader group of countries to participate and collaborate with WGEEL, an important step to allow the GFCM area to participate actively to the recovery of the eel stocks

References

Bevacqua, D., Melia, P., Crivelli, A., De Leo, G. & Gatto, M. 2006. Timing and rate of sexual maturation of European eel in brackish and freshwater environments. Journal of Fish Biology, 69: 200–208.

Ciccotti, E. 2005. Interactions between capture fisheries and aquaculture: the case of the eel (Anguilla anguilla L., 1758) in the Mediterranean. In S. Cataudella, F. Massa & D. Crosetti, eds. Interactions between Capture Fisheries and Aquaculture: a methodological perspective”, pp. 190–203. Studies and Reviews. General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean No. 78. Rome, FAO.

Commission of the European Communities. 2002. Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament laying down a Community Action Plan for the conservation and sustainable exploitation of fisheries resources in the Mediterranean sea under the Common Fisheries Policy. COM 535 Final. 37 pp.

Dekker, W. 2002. Status of the European eel stock and fisheries. Proceedings of the International Symposium Advances in Eel Biology. Tokyo, Japan, 28–30 September 2001.

ICES. 2001. Report of the ICES/EIFAC Working Group on Eels. ICES C.M. 2002/ACFM:03.

Moriarty, C. 1990. European catches of elver of 1928–1988. Internationale Revue der gesamten Hydrobiologie 75:701–706.

Moriarty, C. 1996. The European eel fishery in 1993 and 1994. First report of a working group funded by the Europea Union Concerted Action AIR A94-1939. Fisheries Bulletin (Dublin), 14, 52 pp.

Study Group on International Post-evaluation on Eels (SGIPEE). 2011. Report of the Study Group on International Post-evaluation on Eels. London, UK, 24–27 May 2011. ICES CM 2011/SSGEF:13. 39 pp.