Fishery trends eels

Anguilla spp. are found in marine, brackish and fresh waters all around the world, where they are fished constantly because of their accessibility and market demand. The catch (FAO 2002b) is comprized of European eels (Anguilla anguilla) in Europe; Japanese eels (A. japonica) and “river eels” in general in Asia; European eels in Africa; American eels (A. rostrata) in North America; and “river” and short-fin eels (A. australis) in Oceania. EIFAC/ICES (2001) term “river eels” as all glass eel and elvers caught for export.

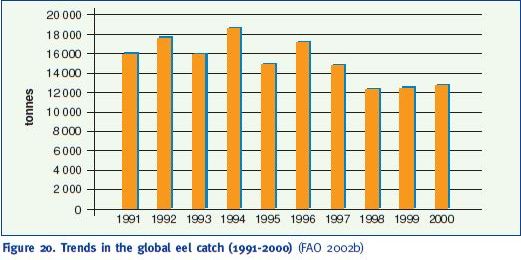

Since 1994 (Figure 20) there has been a global decline in eel catches, from a peak of 18 600 tonnes in 1994 to 12 700 tonnes in 2000. A portion of these figures are glass eels and elvers, so they do not accurately reflect the actual catch.

Figure 20. Trends in the global eel catch (1991-2000) (FAO 2002b)

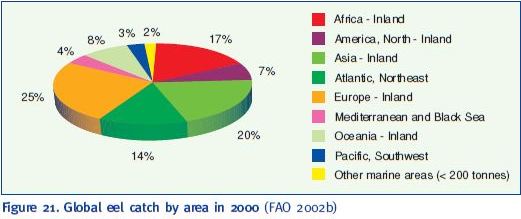

In 1998, the International Council for Exploration of the Sea (ICES) declared the eel spawning stock to be beyond safe biological limits (FAO/ICES/ACFM 1998). In 2000, the global capture totalled 12 700 tonnes, with Europe the leading continent with 5 300 tonnes, followed by Asia (2 400 tonnes), Africa (2 300 tonnes), Oceania (1 600 tonnes) and North America (1 100 tonnes). 77 percent of the catch is from inland waters, with Europe, followed by Africa and Asia, the major areas. The major marine areas where eels are caught are the Northeast Atlantic and the Mediterranean and Black Seas (Figure 21). In 2000 Egypt was the leading country where eels were caught, followed by Indonesia and New Zealand (Figure 22).

Figure 21. Global eel catch by area in 2000 (FAO 2002b)

In New Zealand, there is a sizeable fishery for both A. australis and A. dieffenbachii. Although total landings for the decade have averaged around 1 300 tonnes annually, they have declined to an average of about 1 100 tonnes since 1996. The New Zealand fishery has had a quota since 2000 and now the maximum harvest is essentially determined (S. Tibbetts, pers. comm., 2002).

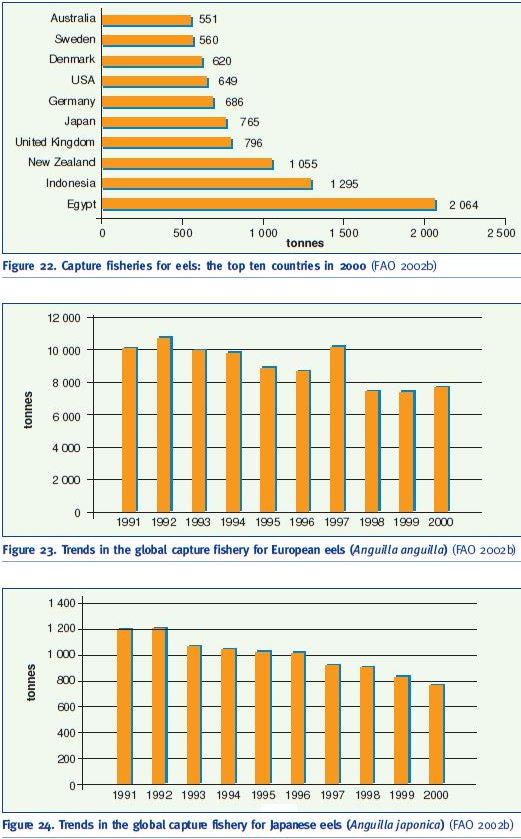

The data from 1991 to 2000 for the European eel (Anguilla anguilla) show a marked decline from peak of over 10 000 tonnes; for the last three years of the decade the catch was less than 8 000 tonnes (Figure 23). The European eel catch was spread throughout western Europe and North Africa in 2000 (Table 7). The catch of Anguilla anguilla in inland waters totalled over 5 400 tonnes in 2000, with the bulk caught in Europe (57 percent) and Africa (40 percent) (FAO 2002b).

Figure 22. Capture fisheries for eels: the top ten countries in 2000 (FAO 2002b)

Figure 23. Trends in the global capture fishery for European eels (Anguilla anguilla) (FAO 2002b)

Figure 24. Trends in the global capture fishery for Japanese eels (Anguilla japonica) (FAO 2002b)

Table 7. Catch data for European eels (Anguilla anguilla) by country in 2000 (FAO 2002b)

Country European eel catch (tonnes)

Egypt 2 064

United Kingdom 796

Germany 686

Denmark 620

Sweden 560

Italy 549

Poland 429

Netherlands 351

Norway 281

Ireland 250

The global catch of Anguilla japonica shows (Figure 24) a similar trend to figures from Europe. In 1990 the total for this species was 1 280 tonnes, distributed between Japan, Korea, Taiwan Province of China and Guam, while in 2000 the total had fallen to 765 tonnes, caught only in Japan.

The American eel is caught only in North America (1 100 tonnes); the catch is mainly from inland waters and in the Northwest Atlantic, with 650 tonnes in the United States and 450 tonnes in Canada. The 2000 catch in Canada was the lowest for 49 years (EIFAC/ICES 2001). In the USA, the American eel fishery area extends from Maine to the Gulf of Mexico. In Canada the fishery areas are in Ontario and Quebec but, in the last two decades, Newfoundland, New Brunswick and Scotia-Fundy have also become important. This species is also captured in Mexico and the Dominican Republic.

The dramatic fall in numbers and volumes over the last decade indicates that all species of eel are under pressure, either from fishing activities or from environmental degradation.