Trends in aquaculture production - eel

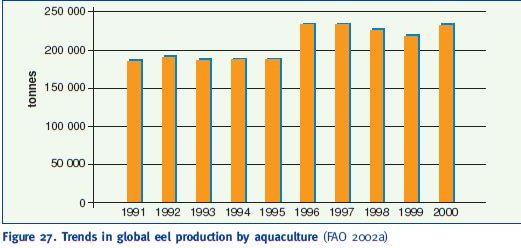

Global eel aquaculture has shown an increasing trend from 1991 to 2000; rising from about 185 000 tonnes in 1991 to levels of about 230 000 tonnes since 1996 (Figure 27). Global demand for eels is estimated at about 200 000 tonnes/year (Frost et al. 2000).

Production is predominantly based on the culture of the European eel (Anguilla anguilla) in Europe, Japan and China, and the Japanese eel (A. japonica) in China, Taiwan Province of China and Japan. Most of the global increase in production has been seen in China, which is now the major producer. This has been due to the increasing intensification of farming systems and the diversification from A. japonica to A. anguilla. There are a number of reasons for this shift. Firstly, Japanese glass eels have been undersupplied. Secondly, European glass eels have a price advantage. Thirdly, Chinese eel farmers have gradually developed better farming methods for European eels, which make it possible to raise them on a larger scale. In 1998, China was reported to have produced 50 000 tonnes of European eels (Frost et al. 2000) but this is not specifically recorded in FAO statistics (FAO 2002a); the whole of Chinese production is recorded as A. japonica. Recently there has also been some culture of Anguilla rostrata in Asia. It is estimated that production is between 3 000 and 5 000 tonnes (www.glasseel.com).

There has also been an increase in the production of A. anguilla by farms in the Netherlands and Denmark, which appears to have occurred as a result of increased marked demand from Japan and the introduction of more intensive production techniques, including the use of commercially available re-circulating aquaculture systems. However, the production of short-fin eels (A. australis) is still small in Australia and New Zealand.

The combined effect of the introduction of new species to traditional eel culture locations and systems intensification has substantially increased the production and value of the global eel aquaculture industry over the last decade.

Figure 27. Trends in global eel production by aquaculture (FAO 2002a)

Asia was the major continental producer in 2000, with 222 000 tonnes, accounting for 95 percent of total eel production. Europe followed with 10 600 tonnes, Africa (73 tonnes) and Oceania (26 tonnes) were minor producers. 220 000 tonnes of Japanese eel (A. japonica) and 2 000 tonnes of “river eel” were produced in Asia, while European and African production consisted entirely of the European eel (A. anguilla). In Oceania, the data refers to short-fin eels (A. australis). FAO statistics are regarded as underestimates, since they do not include the production of European eels in China: in 1998, China produced 50 000 tonnes of European eels (Frost et al. 2000).

Global production in freshwater reached 228 000 tonnes in 2000, consisting of 217 709 tonnes of Japanese eels and 326 tonnes of river eels in Asia, followed by nearly 9 986 tonnes in Europe (all European eels) and 20 tonnes in Africa. In brackish waters, production was nearly 4 500 tonnes: about 4 064 in Asia (57 percent Japanese eels), 321 tonnes in Europe, 53 tonnes in Africa and 26 tonnes in Oceania. Maricultured eel production is present only in Europe (310 tonnes).

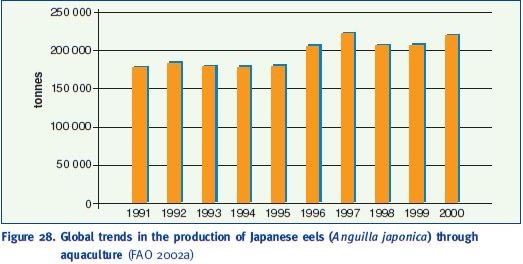

Single species data shows that Japanese eel production rose from 178 000 tonnes in 1991 to peaks of 223 000 tonnes in 1997 and 220 000 tonnes in 2000 (Figure 28). This species is produced only in Asia, both in brackish and freshwaters, where the production was 2 300 tonnes and 217 700 tonnes, respectively.

Figure 28. Global trends in the production of Japanese eels (Anguilla japonica) through aquaculture (FAO 2002a)

Table 11 shows the main producing countries for Japanese eels. Japan is also an important eel market, consuming more than 100 000 tonnes in 1996 (www.ecoscope.com/ eelbase).

Table 11. Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica) production by country (2000) (FAO 2002a)

Country (tonnes)

China 160 740

Taiwan Province of China 30 480

Japan 24 118

Korea, Republic of 2 725

Malaysia 1 980

TOTAL 220 043

In Japan, eel farms are located mainly in Aichi, Kagoshima and Shizuoka, followed by other prefectures such as Miyazaki, Kochi, Tokushima and Mie. There has been a significant decline in the number of eel farmers, due to several reasons: aging of farmers and a shortage of successors, a dramatic decline in wild eel numbers, competition from imports, and rising costs for elvers and farm production. The number of eel farmers in Japan peaked in 1973 (3 250), but fell by 80 percent to 651 households in 1997. Total yield in Japan, including both wild and farmed eels, peaked at 41 094 tonnes in 1985. Yields over the past five years are shown in Table 12 (www.wtco.osakawtc.or.jp/e/market/item/eels.html). In 1998, 96 percent of the eels produced in Japan were farmed.

Table 12. Total yield of wild and farmed eels in Japan

Yield (tonnes)

1994 29 431

1995 29 131

1996 28 616

1997 25 031

1998 22 845

In Thailand, Thai Unagi Co Ltd started an eel farm in Chacheongsao in 2000 which is expected to raise an annual total of 10 000 glass eels (Anguilla japonica) imported from Taiwan Province of China. Domestic consumption of eels in Thailand totals about 300 tonnes/year, of which the company supplies 20 tonnes, with the rest imported as roasted eels (“kabayaki”) from Taiwan Province of China and Japan.

China imports glass eels from Europe. The quantity required by China is falling to a more manageable level, and there were some significant problems for eel farmers in 2002 (www.glasseel.com). Firstly, there was an European ban on imports of Chinese agricultural products of animal origin because of the presence of medicinal residues. Secondly, Japan, the main consumer of eels, was also becoming conscious of the residue problem. In 2002 six

“kabayaki” processing factories in Fujian are unable to export to Japan. New testing protocols for live imports into Japan are causing considerable delays, making it virtually impossible to export live eels from China to that country.

These events stimulated the demand for eels from Taiwan Province of China, where residue testing for veterinary medicines has been practized for a number of years. In spite of all these problems, ex-farm prices of eels in China in 2002 for size 3 pieces increased from € 1.54/kg in January to € 5.50/kg at the start of April, peaking at € 6.80/kg - the breakeven production price is € 4.80/kg. These prices could reflect a market situation where there is an overall shortage of eel stocks in China. For a short time in May 2002, Anguilla japonica eels (250-500 g) reached

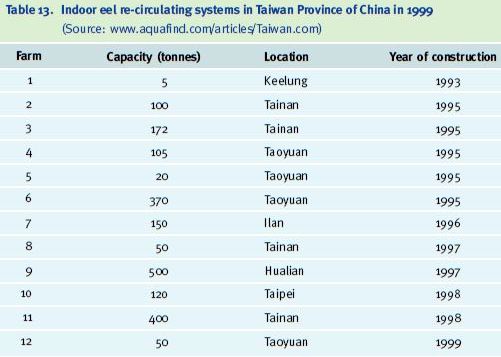

€ 18.8 each (www.glasseel.com). There were 12 indoor re-circulating water production systems for eels In Taiwan Province of China, in 1999 (Table 13).

Table 13. Indoor eel re-circulating systems in Taiwan Province of China in 1999 (Source: www.aquafind.com/articles/Taiwan.com)

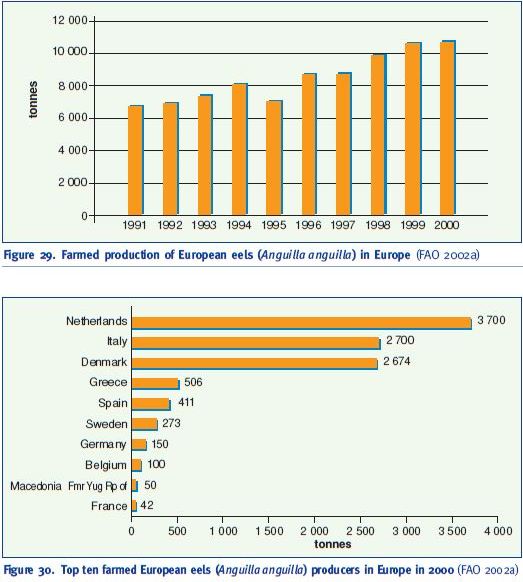

European eel production also increased in the decade to 2000. 6 700 tonnes were produced in 1991 and 10 700 tonnes in 2000 (Figure 29) in Europe. FAO data refers only to European production and does not include production in China; China produced 50 000 tonnes of European eels in 1998 (live weight), corresponding to 30 000 tonnes of “kabayaki” (Frost et al. 2000). European eels are cultured in Europe, Asia, and marginally in Africa, in all environments (brackish water, mariculture, freshwater). The bulk of production in 2000 came from inland waters in Europe, together with about 300 tonnes each from the Northeast Atlantic and the Mediterranean and Black Sea. The leading producer (Figure 30) was the Netherlands (3 700 tonnes), followed by Italy and Denmark (each around 2 700 tonnes).

The capture-based aquaculture of eels is an expanding activity, particularly in the Netherlands and Denmark. Production depends on the availability of glass eels imported from France, Spain and England. In Denmark, it has been calculated that from of a single metric ton of glass eels an eel farm can produce about 200 tonnes (Frost et al. 2000).

Figure 29. Farmed production of European eels (Anguilla anguilla) in Europe (FAO 2002a)

Figure 30. Top ten farmed European eels (Anguilla anguilla) producers in Europe in 2000 (FAO 2002a)

There were 11 eel farms in operation in Greece in 2000, with an annual production of 500 tonnes. Lack of processing facilities, disorganized marketing and, mainly, the lack of quality glass eels or elvers for on-growing have led to relatively low levels of production. The eel farms are small units producing on average 50 tonnes per year with only four farms operating re-circulated water systems.

There is one large company in Valencia, Spain that produces about 300 tonnes/year in re circulation systems. In the Delta del Ebro region there are two producers in open systems (one of them produces 60 tonnes/year), and another in the Basque country using a re-circulation system (60 tonnes/year) (L.P. Igualada, pers. comm. 2002).

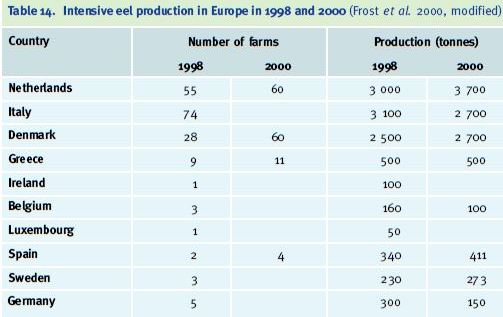

Total production of European eels from brackish waters in 2000 was 374 tonnes, with Italy as leading country (250 tonnes), followed by Greece (56 tonnes) and Morocco (35 tonnes). In mariculture, Spain was the main producer (302 tonnes). The only other producer was Greece (8 tonnes). In freshwater the Netherlands was the leader (3 700 tonnes), followed by Denmark and Italy (2 674 and 2 450 tonnes respectively). Intensive eel production in Europe is shown in table 14.

Table 14. Intensive eel production in Europe in 1998 and 2000 (Frost et al. 2000, modified)

Total production of A. australis in Australia is presently in the order of 500-700 tonnes/year, worth A$ 4.0-7.5 million (www.fisheries.nsw.gov.au/aquaculture/freshwater/eels.htm), the vast majority of which comes from capture fisheries, which historically have been from stock enhanced wild fisheries (also referred to by the industry as “cultured eels”). Further expansion of the industry is presently constrained by the limited application of intensive production techniques and limited access to local glass eel supplies. While a significant commercial fishery exists (both from dams/impoundments and estuaries), and huge export markets are available, the eel farming industry in New South Wales (NSW) is still small. There are over 20 licensed eel farms there but the total production was only 2.4 tonnes for both short-fin and long-fin eel species for the 1999/2000 production year.

In New Zealand, there are no eel farms that operate on a commercial scale. It is illegal to exploit (for commercial purposes) any eel smaller than 220 g (which excludes glass eels). Most of the experimental work is aimed at increasing weight and fat content of yellow eels (200 g grown to 300-400 g) in about 5 farms, while another 5 companies and research organizations are looking at the possibilities of growing on glass eels (0.2 g each), but there will be legal problems in expanding this to a commercial scale (S. Tibbetts and D. Jellyman, pers. comm. 2002).