Fishery trends - grouper

Groupers are highly prized for the quality of their flesh, and most species fetch high market prices. This has led to overfishing in many areas, with species that are commercially favoured showing signs of declining numbers. A large proportion of the world’s groupers are caught in artisanal fisheries, and even low-level artisanal fisheries can adversely affect stocks.

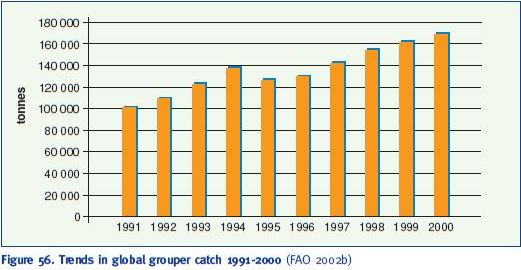

Recreational fishing may also have significant impact on stocks; for example, the recreational fishery of groupers in Florida accounts for between 25% and 35% of the State’s total grouper catch (Morris, Roberts and Hawkins 2000). The global catch of groupers showed a 68% increase from 100 724 tonnes in 1991 to 168 943 in 2000 (Figure 56).

Figure 56. Trends in global grouper catch 1991-2000 (FAO 2002b)

The impact of intensive fishing is worsened by the K-selected life strategies of these genera, their tendencies to form predictable spawning aggregations, and their frequent occurrence on relatively shallow, easily accessible coral reefs, which are severely over-exploited in many parts of the world. For many of these species, spawning aggregations represent the total reproductive activity for a given year, and many species consistently return to the same aggregation area, year after year. Fisheries often target spawning aggregations, since they are consistent in time and space. When fishing pressure removes a high proportion of the fish forming these aggregations, these may quickly decline, and within a few years may cease to form altogether (Johannes et al. 1999, Sadovy and Eklund 1999).

With the rapidly developing economies of China and South-East Asia, the emergence of a wealthy class with substantial disposable incomes has led to an increasing demand for fish in the region (Birkeland 1997). The “live fish trade” of the Indo-Pacific has expanded rapidly in recent years, and now targets many species (Sluka 1997; Johannes and Riepen 1995). Groupers are the most intensively exploited group in the live fish trade, and the high prices paid by exporters to local fishermen mean that target species may be heavily over-fished (Morris, Roberts and Hawkins 2000).

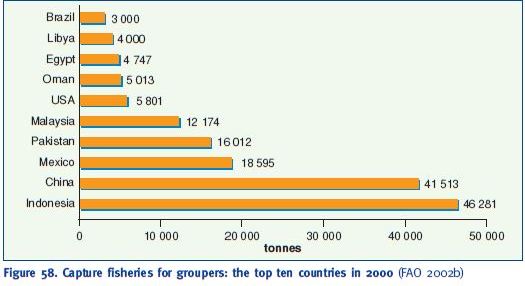

In 2000, most of the grouper catch was reported by developing countries (162 000 tonnes), with only 6 600 tonnes coming from industrialized nations. Asia was the leading continent with 125 100 tonnes, followed by North America (inc. Caribbean and Mexico) with 26 300 tonnes, Africa with 10 400 tonnes, South America with 5 000 tonnes, Oceania with 1 500 tonnes and Europe with 550 tonnes.

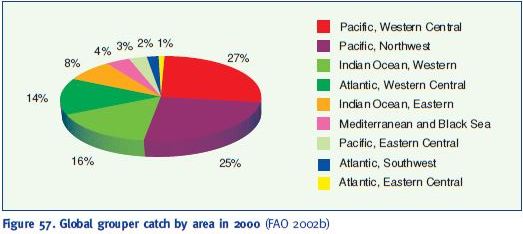

The leading area was the Western Central Pacific (47 000 tonnes), followed by Northwest Pacific (42 000 tonnes), Western Indian Ocean (27 000 tonnes) and Western Central Atlantic (23 000 tonnes) (Figure 57). In the same year, Indonesia was the leading country, followed by China. (Figure 58).

Pacific, Western Central

Figure 57. Global grouper catch by area in 2000 (FAO 2002b)

Trade often follows a pattern of sequential over-exploitation; the most highly sought species are fished-out in country after country, before the less valuable species are targeted and fished intensively (Sluka 1997; Johannes and Riepen 1995).

The incredible prices paid for endangered species in Chinese and South-East Asian markets (in 1997 the red grouper – E. akaara, in Hong Kong fetched US$ 42/kg) (www.spc.org.nc/coastfish/ news/LRF/5/15grouperHK.htm), mean that fishermen will go to great lengths in order to catch every fish, and this has already contributed to regional population crashes of species, including E. akaara and E. striatus (Morris, Roberts and Hawkins 2000; Sadovy 2001).

Figure 58. Capture fisheries for groupers: the top ten countries in 2000 (FAO 2002b)

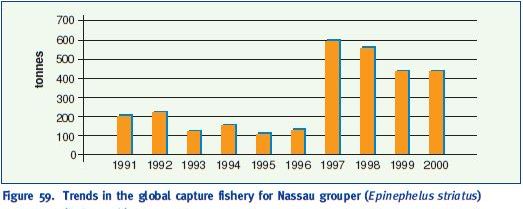

Figure 59 shows the trend in the capture fishery for the Nassau grouper (Epinephelus striatus), for example. This species is caught in North and South America, mainly in the Bahamas (381 tonnes) and Cuba (50 tonnes), – 431 tonnes in 2000 in the entire Western Central Atlantic area. It represents one of the most important commercial groupers in this area and is heavily fished without any consideration being given to its vulnerability through overfishing; this species is considered endangered (Morris, Roberts and Hawkins 2000).

Figure 59. Trends in the global capture fishery for Nassau grouper (Epinephelus striatus) (FAO 2002b)

There is a strong link between fishing activity and the capture-based “seed” used for farming, with declines in premium species from the overfishing of grouper adults. However, the reasons for this decline cannot be evaluated without careful, controlled studies, as falling catches may in fact be due to a combination of different causes: overfishing of the adults which produce the juveniles, habitat degradation and pollution, destructive fishing techniques, high export demand, etc. (Johannes 1997; Sadovy 2000). Grouper fishery trends suggest that a more holistic approach to establish the links between adults and juveniles is necessary.