National and regional fishery management

According to the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (FAO 1995), conservation and management measures, whether at local, national, sub-regional, or regional levels, should be based on the best scientific evidence available and designed to ensure the long-term sustainability of fishery resources. The measures used should promote a rational exploitation, possibly below MSY, while maintaining the availability of the resource base for present and future generations.

Within fisheries under national jurisdiction, States should identify the relevant domestic parties having a legitimate interest in the use and management of fisheries resources and seek their cooperation in achieving responsible fisheries.

For stocks exploited by two or more States (either transboundary, straddling or highly migratory fish stocks) there needs to be cooperation to ensure effective conservation of the resources and management of the fisheries. This should be achieved by the setting up of bilateral, sub-regional or regional fisheries organizations or arrangements. A sub-regional or regional fisheries management organization or arrangement should possibly include States under whose jurisdiction the resources occur, as well as States which have a real interest in the fisheries even though the resources are outside their national jurisdiction. States and sub-regional or regional fisheries management organizations and arrangements should ensure that the laws, regulations and other rules governing their implementation are accepted by all parties (FAO 1995).

Many regional fishery bodies foresee a two-tiered structure; in this concept a scientific entity, either a subsidiary or an independent body, provide scientific advice to the regional fisheries management organization. Indeed, there are two different approaches to developing scientific advice. One approach is based upon a “science secretariat”, with has its own independent staff. The Oceanic Fisheries Programme (OFP), the IATTC (Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission), the NAFO (Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization) and others utilize this system. However, the majority of the Regional Fisheries Management Organizations rely on a “multinational approach”, where scientists from different national institutes of the Member States meet regularly to develop and agree on scientific advice as instructed by the management body.

The source and availability of staff is the key feature that distinguishes science secretariats (independent staff) from multinational approaches (national scientists) and that may influence the nature of the advice, because compromises are most likely to occur at an early stage in the second approach. The ICCAT (International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas), the GFCM (General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean), CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) are examples of such “multinational” scientific approach that are widely utilized. This approach tends to predominate, because Member States prefer an approach that has low up-front costs and secures their individual, immediate and direct involvement in the fishery’s scientific research and subsequent input to management (Ward, Kearney and Tsirbas 2000).

In both cases, the monitoring and state of the resources can be compromized where important fishing nations are not parties to the Regional Fisheries Management Organization or arrangement. Difficulties may also occur where fishing activities outside the jurisdiction of an authority take targeted or incidental catches of species that are under the responsibility of the administration, as is the case of some highly migratory stocks, e.g. bluefin tuna in the Mediterranean and North Atlantic.

Bluefin tuna management – an example for capture-based aquaculture

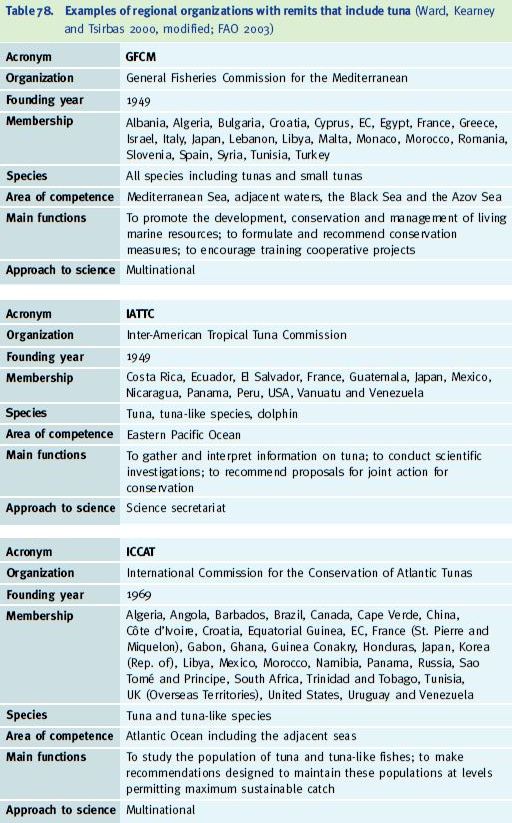

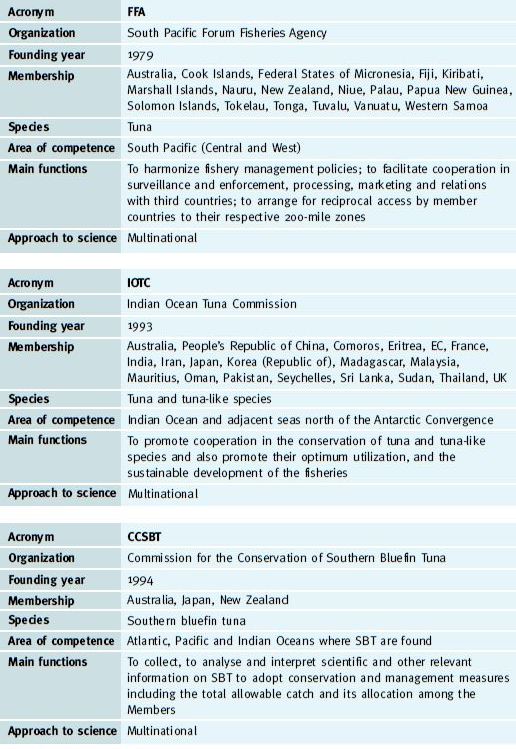

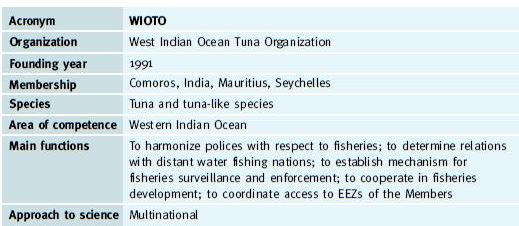

Two examples of the regional management of capture-based aquaculture, both of tuna, are provided in this section of the report; regional organizations with a remit that includes tuna are listed in Table 78.

The southern bluefin tuna and the CCSBT

The first example is provided by the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT), which has the responsibility for the management of the stock. Since 1985, Australia, Japan and New Zealand have met to negotiate annual global quotas for southern bluefin tuna (Figure 144). Since 1994, these negotiations have been under the auspices of the CCSBT (1994) and involve the setting of an annual TAC and the negotiation of national allocations (quotas) within that TAC. Each year, discussions on allocation are preceded by a scientific meeting involving scientists from the three Member countries, who exchange scientific data and provide an assessment on the state of the stock. Increased scientific effort has been warranted, given the massive decline in catch but it took several years to reach agreement. Since 1990 there has been a strict annual quota of 11 750 tonnes (Haward and Bergin 2001) of which each Member has been allocated a constant share (Japan: 6 065 tonnes; Australia: 5 265 tonnes; New Zealand: 420 tonnes). The Republic of Korea and Taiwan Province of China became active in the CCSBT in 2001 and 2002 respectively; for the 2003-4 season they were each allotted catch limits of 1 140 tonnes, while the limits for the other countries remained the same. This compares with the peak output of the southern bluefin tuna fishery of 81 000 tonnes in 1961, before stringent quota reductions were applied to prevent stock collapse. The southern bluefin tuna population today is thought to be so severely depleted that the Convention for International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES) has listed the species as “critically endangered” in its “Red List” of endangered species.

Figure 144. Southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) (Photo: L. Mittiga)

CCSBT has also introduced a trade information scheme to track the point of origin of southern bluefin tuna. This proposal had been mooted for several years, following the introduction of a similar scheme by ICCAT. In addition, a southern bluefin Statistical Document Programme (SDP) was launched in June 2000 (Haward and Bergin 2001). It includes the principle that “there is no waiver” of the requirement that all imports of southern bluefin tuna into the territory of a

Member of the CCSBT shall be accompanied by a CCSBT Southern Bluefin Statistical Document. The scheme is also based on the principle that the programme will conform to “relevant international obligations”. One of the interesting elements where information is required is for capture-based farmed tuna, thus taking into account the significance of farmed southern bluefin tuna in Australia. As in other schemes, an official of the each vessel’s flag State, or its “delegated entity”, endorses the Southern Bluefin Statistical Document that accompanies the landing of the fish. Data obtained from the programme is then forwarded to all Members twice a year. Members then check export statistics against the data provided to them from the CCSBT Secretariat.

It should be noted that, following the explosion of tuna capture-based aquaculture, the quota of one Member (Australia) was year by year completely utilized by the farming industry until the CCSBT imposed a cap on the maximum amount of juvenile catch to be taken for this purpose. The southern bluefin tuna collected by the fishery and transferred to the capture-based aquaculture system are monitored by the Federal Fishery Management Authority (that administers the wild fishery), which estimates the total live tuna collected for farming by each operator and deducts it from its TAC.

The northern bluefin tuna and the ICCAT

The second example is provided by the Atlantic and Mediterranean1 large pelagic fisheries that are under the competence of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), which was established in 1969 with the aim of coordinating international research and management of highly migratory tunas and billfish in the Atlantic and adjacent waters. ICCAT is currently composed of 32 members and is endowed with a Standing Committee on Research and Statistics (SCRS) that provides scientific advice to the Commission, The SCRS conducts stock assessments of Atlantic tunas and billfish and coordinates multinational research activities related to these species. The stock assessments, upon which the Commission bases its decisions, change from year to year in response to improved methodologies and revised statistics.

ICCAT’s primary stated bluefin management goal is to maintain Atlantic bluefin tuna populations at levels that will allow the Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY). The MSY is an estimate of the greatest average catch that can be removed from fish stocks year after year, without reducing the stock’s ability to sustain these maximum catches in subsequent years (Buck 1995). In an effort to achieve this aim, ICCAT recommended a number of management measures for the Western Atlantic bluefin fishery, which included harvest quotas, per trip catch limits, and a minimum size limit (currently 6.4 kg).

In 1981, ICCAT decided to manage the Eastern and Western Atlantic bluefin tuna stocks as discrete populations, setting a conventional boundary at 45°W. This two-stock hypothesis is supported by the presence of small to large specimens on both sides of the Atlantic, the occurrence of spawning in the Gulf of Mexico and the Mediterranean at different times of the year, and morphometric differences between fish from different areas. Analysis of conventional tagging data, which show a low fish-mixing rate with most tags recaptured in the area of release, also gives support to the existence of two separate groups of bluefin tuna in the North Atlantic (Arnold et al. 2003). Several electronic tagging programmes have been initiated recently; these include experiments with “pop-up” satellite-detected tags carried out in Europe between 1998 and 2000 (Arnold et al. 2003) and in Canada and New England since 1997 (Lutcavage et al. 2003). Additional research is needed for a better understanding of tuna biology, including the

1 In the Mediterranean, large pelagic fisheries are also under the competence of the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM). GFCM and ICCAT have established a Joint Working Party to monitor the status of tuna and tuna-like species.

movements of reproductive habitat and spawning site fidelity. There is also a need for a genetic survey of the bluefin tuna and its Mediterranean and Atlantic distribution to understand if mixing occurs between the two stocks; some results are already available, and various studies are currently in progress (Magoulas 2002; Pla 2002).

In 1981, ICCAT initiated a stock recovery plan for the Western Atlantic bluefin population. The Commission recommended that the scientific monitoring quota should be as low as possible for the Western Atlantic and this was set at 1 160 tonnes for the 1982 fishing season in the Western Atlantic but was increased to 2 660 tonnes for 1983 (Buck 1995) and remained at this level until 1992. Between 1993 and 2001 the quota, which is revised at two-yearly intervals, ranged between 1 995-2 500 tonnes. Current catches from the western stock are modest, but the stock is still considered as over exploited (Tudela 2002b). ICCAT also developed a management regime for the eastern stock and the MSY was set at 29 500 tonnes for the Eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean, with quotas (TACs) allocated on a State by State basis. The 1998 stock assessment for the Eastern Atlantic bluefin tuna, as analysed by the SCRS, showed that breeding population levels had declined alarmingly.

Capture-based tuna farming now complicates the stock assessment in the Mediterranean area, due to the transhipments of tuna “at sea”. In the Mediterranean, owing to the absence of EEZs, the stock has the potential for much greater common ownership, and this gives rise to conflicting data. The main problem is that it necessary to know the characteristics of the fish when they are first caught (size, location, fleet/gear used, and the amount of fishing effort spent in capturing them) (ICCAT 2003). Biological sampling is necessary to understand the age and structure of the populations. Today it is more difficult to know the precize biological composition of a catch, since tuna are not landed to local buyers but are transferred live at sea. There, the counting of the fish is often done by divers equipped with underwater cameras to estimate fish length and the size composition of the catch (giving total weight). However, the results are still crudely estimated.

Capture-based tuna farming has raised other issues, due to the lack of information on growth and conversion rates in cages, data that is required for the BTSD to back-calculate weight at catch. The challenge is to ensure that the tuna catches sold to tuna farmers are reported for both stock assessment and quota purposes. The difficulties related to collating the data received from most of the Mediterranean tuna farms and national authorities in 2001 has led ICCAT to estimate that tuna gain an average of 25% of their body weight during the farming period. This has led to a conversion factor of 0.8 that is applied to farmed products imported by Japan, which is used to back-calculate the weight of the catches before the capture-based aquaculture period.

ICCAT introduced a Bluefin Tuna Statistical Document (BTSD) programme for frozen bluefin in 1993 and for fresh bluefin in 1994. The aim of the programme was to increase the accuracy of bluefin statistics and track unreported fish caught. The programme requires that all contracting parties must report all imported bluefin tuna, and that these records are accompanied by an ICCAT BTSD detailing the weight and type of products by flag of the fishing vessels and area of fishing operations (Miyake et al. 2003).

There is general agreement that capture-based aquaculture should be developed within a Best Management Practice framework. For this purpose GFCM and ICCAT established a Joint ad-hoc Working Group on Sustainable Tuna Farming Practices in the Mediterranean in 2002. The Working Group is composed of scientists from the GFCM Scientific Advisory Committee and the GFCM Committee on Aquaculture, and of scientists from the ICCAT SCRS.

Table 78. Examples of regional organizations with remits that include tuna (Ward, Kearney and Tsirbas 2000, modified; FAO 2003)

The southern and northern bluefin tuna populations are examples of capture-based aquaculture target pelagic species. They are highly migratory and, being a shared resource, responsible management requires common rules, which need to be adopted and properly enforced in all the distribution areas of each species. ICCAT, GFCM and CCSBT face many complexities and difficulties in order to improve their management, and specific new rules have to be implemented to deal with the tuna capture-based aquaculture issue. The high economic value of the species and market interests will inevitably make solutions challenging.