DESCRIPTION OF CAPTURE FISHERIES

General fisheries

Most of the Pangasiid catfishes are important species in capture fisheries of the Mekong basin, generally as elements of a diverse range of multi-species fisheries throughout the basin.

Pangasianodon hypophthalmus is particularly important in the fisheries of the Tonle Sap River and the Great Lake of Cambodia, for instance in the bagnet, or dai fisheries in the Tonle Sap River targeting a range of migratory fishes at the beginning of the dry season. They are also important in floodplain fisheries of the lower basin, in southern Cambodia and the Mekong delta in Viet Nam.

Larger specimens are caught sporadically in the Mekong mainstream and in the Sesan-Srepok-Sekong river systems in northern Cambodia. In the spectacular Khone Falls fisheries, targeting migratory species crossing the falls, the species is rarely encountered and is only caught extremely infrequently above the falls in Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Thailand.

Pangasius bocourti are captured throughout the lower Mekong basin. In Cambodia and Viet Nam, it is much less frequently caught than Pangasianodon hypophthalmus. However, upstream in Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Thailand, it is caught in large numbers in gillnet fisheries on the Mekong mainstream and larger tributaries, particularly during their upstream migrations at the beginning of the monsoon season.

During the same period, significant numbers of Pangasius bocourti are also captured at the Khone Falls trap fisheries on the border between Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Cambodia, when the species take part in spectacular, multispecies migrations through the falls (e.g. Baird, 1998).

Both snakehead species are extremely important in capture fisheries throughout the basin. Channa striata is one of the most important species in the Mekong and is mainly captured in floodplain and rice field habitats. Channa micropeltes is most commonly captured in sections of the river basins with maintained, natural floodplain habitats, such as the Tonle Sap River and Great Lake ecosystem and the Songkhram River in Thailand.

Capture of juvenile Pangasiid catfishes

Large numbers of river catfish larvae (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus) were, until recently, caught in the upper Mekong delta near the border between Viet Nam and Cambodia. The fishery was concentrated in Chao Doc and Tan Chau districts of An Giang Provinces in Viet Nam, and in Kandal province of Cambodia.

The fishery occurs over 2–3 months at the beginning of the monsoon season (May–July) when the larvae drift downstream in the Mekong mainstream towards

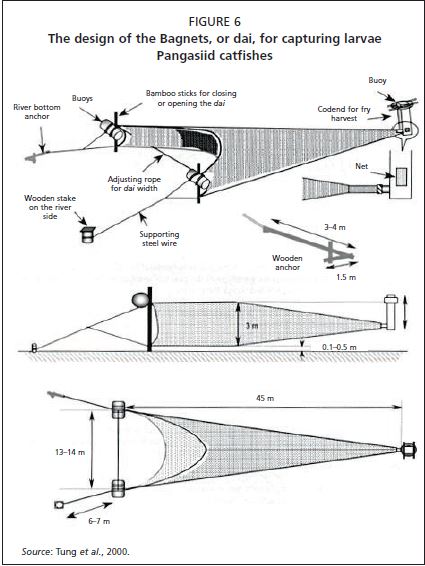

Figure 6

The design of the Bagnets, or dai, for capturing larvae Pangasiid catfishes

tiny, fragile fish larvae (Figure 6). The dais are typically harvested 3 times daily.

Limited quantitative data are available on this fishery. Estimates from 1977 suggest that 200 to 800 million fry, 0.9–1.7 cm in length, were caught annually (based on data from An Giang Department of Agriculture, cited in Trong, Hao and Griffiths, 2002). A small amount of other Pangasiid larvae are caught in this fishery and used for grow-out, particularly Pangasius bocourti, Pangasius conchophilus and Pangasius larnaudiei.

In 1977, Dong Thap and An Giang province had a total of 1 974 stationary dais for the collection of river catfish larvae, of which 204 were state owned, while 1 770 were owned by private individuals. The mean daily yield from each stationary dai was 13 100 larvae, with a total estimate of 763 million river catfish larvae being harvested in 1977 (Huy and Liem, 1977). Tung et al. (2000) reported a total production of 200 million river catfish larvae in 1996.

From the 1950–1980s, approximately 2 000 farmers in Hong Ngu, and Tan Chau districts of An Giang province and Chau Doc district of Dong Thap province raised wild river catfish larvae to fingerlings. The annual production of river catfish fingerlings was 50–100 million.

In the wild fishery, non-Pangasiid catfishes were either thrown back or used as fish feed (Bun 1999; Van Zalinge et al., 2002). Only an estimated 5–15 percent of the larvae harvest was river catfish and an estimated 5–10 kilogram of other fish species were killed for each kilogram of river catfish fry caught (Phuong, 1998). Bycatch of non-target larvae was higher in Viet Nam than Cambodia probably because there were lower numbers of larvae within Vietnamese waters (Van Zalinge et al., 2002).

Pangasius bocourti larvae that were 10–20 days old were also taken as a bycatch by the stationary dai fishery for river catfish. There is also a small, but specific hook and line fishery for Pangasius bocourti fingerlings of 12–15 cm length in Viet Nam between August–October. These fingerlings typically sell for VND 3 000–4 000 (approximately US$0.19–0.25) each for use as cage aquaculture seed.

The dai fishery for catfish larvae was banned in both An Giang and Dong Thap provinces in March 2000, due to its perceived negative impacts on the wild stock of both target and non-target species (Ish and Doctor, 2005). Before the ban, the provincial authorities auctioned the fishery annually to the highest bidder.

Table 1

Estimated numbers of Pangasianodon hypophthalmus caught in the An Giang province dai fishery, Viet Nam

Year Number of fry caught

(million) References

1977 200–800 Khanh, 1996

1994 62 Tung et al., 2001b

1995 60 Tung et al., 2001b

1996 56 Tung et al., 2001b

1997 48 Tung et al., 2001b

1998 36 Tung et al., 2001b

1999 27 Tung et al., 2001b

2000 0.4 Tung et al., 2001b

2006 0.11 Phuong (Personal communication) 1 Mainly in Dong Thap province

The fishery for juveniles in Cambodia was outlawed in 1994 but collection was still reported in 1998 (Edwards, Tuan and Allen, 2004). So and Haing (2006) estimated that in 2004, a total of 20 million fingerlings from a range of different species were caught from rivers for aquaculture purposes. Approximately 18 percent of these were Pangasiid catfishes, including Pangasianodon hypophthalmus (1.1 million), Pangasius conchophilus (900 000), Pangasius bocourti (600 000) and Pangasius larnaudiei (400 000) (Data based on official statistics of the Department of Fisheries, Cambodia, published in So and Haing, 2006).

Table 1 shows that there has been a massive decrease of wild-caught Pangasiid fry in An Giang province since 1977 to almost zero today following enforcement of the ban.

Unlike Pangasianodon hypophthalmus, Pangasius bocourti larvae cannot be caught in significant numbers in larvae dai nets. Larger juveniles are instead caught by specialised hooks, particularly in Cambodia.

Capture of juvenile snakehead

The spawning habits of snakeheads make them relatively easy targets for fishers, who can visually identify parents guarding their offspring in the shallows of rice fields and floodplains, and then simply “scoop up” the fry with small nets. This is the main method for obtaining snakehead fry from the wild throughout the lower Mekong.

However, juvenile snakeheads are also caught in a variety of fisheries during the monsoon season. Examples include:

• River dai fisheries in Viet Nam and Cambodia;

• Floodplain fisheries using various traps, cast-nets and lift-nets in Viet Nam and Cambodia;

• Large lift-nets (operated from boats) in upper tributaries such as the Songkhram River, Thailand, and Nam Ngum, Lao People’s Democratic Republic;

• Great Lake fisheries, including various traps, seine nets, cast-nets (mainly for Channa micropeltes); and

• Rice field fisheries throughout the lower basin (mainly for Channa striata). These are all multispecies fisheries that do not target any single species. The catches are sorted immediately after capture and snakehead juveniles kept and sold to cage culture operators (often through middlemen). Other large and high-value species are also taken for retail marketing, whereas the bulk of the catch of low-value fish is used for processing (e.g. fish sauce), livestock or aquaculture feed (including for snakehead culture).

In Cambodia, snakehead fingerlings are the most common species in juvenile fisheries. According to the 2004 official statistics from the Department of Fisheries (DOF), more than 15 million fingerlings of Channa micropeltes were caught in

Cambodian waters, constituting 77 percent of all captured fingerlings (So and Haing, 2006). By comparison, the number of captured Channa striata was insignificant (approximately 18 000).

In Thailand and Lao People’s Democratic Republic, snakehead farming is also important, but no quantitative data are available on the capture of wild seed. Channa striata is produced in hatcheries, whereas Channa micropeltes is captured from wild stocks on a seasonal basis (Simon Funge-Smith, personal communication).