DESCRIPTION OF CLARIAS SPP. AND ITS USE IN AQUACULTURE

Taxonomy and life cycle

There are 58 species in the genus Clarias (Siluroidei, Clariidae) recognized in FishBase (2007), all living in freshwater, but able to tolerate salinities up to 2.2 ppt (Clay, 1977). Two species are the focus in the present study, namely Clarias gariepinus, and Clarias jaensis (Figure 1). Both are catfishes from the Clariidae family, which distinguish themselves from the other genera of the family by the presence of a single, long dorsal fin that extend nearly to the caudal fin base, among other distinguishing features.

The naked mucus-covered body is elongate, eel-like, the head is flattened, and eyes are small. Clarias gariepinus grows bigger (maximum size recorded 1.7 m total length, in comparison to 0.5 m for Clarias jaensis) (Pauguy, Leveque and Teugels, 2003). The skin of Clarias gariepinus is thicker than that of Clarias jaensis. The cephalic bones of the latter are almost visible throughout the relatively shorter and smoother under-surface of the head.

Clarias jaensis is the easier to handle of the two and shows a quieter behaviour in the rearing environment. Clarias gariepinus is usually dark spotted greyish coloured; Clarias jaensis is more dark yellowish. After cooking, Clarias jaensis’ bones soften so that the whole fish can be consumed. According to the fishers in the Nkam Valley, Clarias gariepinus is the desirable and preferred aquaculture candidate, while Clarias jaensis is fovoured in traditional dishes and for marriages and other customary celebrations.

Figure 2

Distribution of Clarias catfish in Africa (after De Graaf and Janssen, 1996)

Clarias gariepinus, generally considered to be the most important clariid species for aquaculture, has almost pan-African distribution, ranging from the Nile to West Africa and from Algeria to South Africa. Clarias jaensis’ distribution is less known. In Cameroon, this species is found in the Wouri and the Sanaga river basins, usually sympatric with the introduced Clarias gariepinus. The broad adaptive capabilities of Clarias species allowed their introduction to Europe, the Middle East and Asia (Figure 2).

These clariid species are found in lakes, streams, rivers, swamps and floodplains, many of which are subject to seasonal drying. The most common habitats of these species are floodplain swamps and pools where the catfish can survive during the dry seasons due to their accessory air breathing organs (De Graaf and Janssen, 1996).

Gonadal maturation in Clarias gariepinus is usually associated with the rainy season. In Cameroon, reproduction begins in late March-early April with the start of the rainy season. Heavy flooding in the Nkam Valley is observed by October–November, and fingerling collection takes place a month later when the water recedes back to the river bed. Flood ponds are harvested from January to March, with production varying from 200 to 800 kilogram/100 m? pond. The average individual fish weight is 167 grams.

Fishery exploitation of Clarias catfish

Total freshwater fish production of catfish from the genus Clarias is estimated at 75 000 tonnes and is second only to Tilapia among the freshwater fish species captured in Cameroon (Ngok, Njamen and Dongmo, 2005).

In the Sanaga and Wouri River basins, total capture fisheries production is estimated at 15 000 and 4 000 tonnes, respectively. From this, catfish can be reasonably estimated to contribute approximately one third of the catch, i.e. 6 000 tonnes. The total national production of Clarias catfish may be close to 20 000 tonnes.

The collection of wild Clarias fingerlings for aquaculture is less important than fishing for direct human consumption. In Cameroon the collection of catfish juveniles for aquaculture is specific to the Nkam River basin while it remains a marginal activity in other rivers where Clarias spp. are fished.

Wild Clarias fingerlings

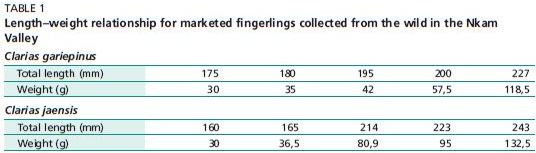

The weight of fingerlings collected for aquaculture ranges between 20–120 grams. Table 1 shows the length-weight relationships for the most commonly marketed fingerlings in the Nkam Valley.

Clarias are relatively robust fish and tolerant of low dissolved oxygen water levels. Clarias jaensis demonstrates a quieter behaviour, and is thus easier to handle compared to Clarias gariepinus. Nevertheless, the holding and feeding of fingerlings is problematic in Cameroon. The most common error is stocking with different sizes in the same container. As larger fish cannibalize smaller individuals, survival rates of less than 10 percent are common and can occur in less than 5 days of stocking. Another problem is artificial feeding. Uneaten feed rapidly deteriorates water quality, causing high mortalities among smaller fish and swollen bellies in larger specimens.

TABLE 1

Length–weight relationship for marketed fingerlings collected from the wild in the Nkam Valley

Source: Pouomogne and Mikolasek, 2007.

Tilapia-Clarias polyculture

Nile tilapia is the most commonly farmed fish in Cameroon. In mixed-sex culture, this species produces large numbers of unwanted juveniles. Overcrowding is controlled by using predator fish. Clarias gariepinus is the most commonly utilized species for this. Large fingerlings of 15 grams are stocked with Nile tilapia at a 1:1 ratio and reared for 9 to 11 months. Unfortunately, catfish fry production from existing hatcheries in Cameroon is poorly organized and managed, and unit prices may vary from US$0.1 to 0.25. A recent economic analysis showed that at the current fish seed price of US$0.2 per 5 gram fingerling most rural farmers are losing money, as farm profitability is possible only with a fingerling unit price of US$0.1 or less (Brummett, 2005; Sulem et al., 2007). When wild seed are available, prices of Clarias gariepinus fingerlings are generally lower than US$0.1.

Clarias fingerling production and the benefits of wild-caught juveniles African catfish reproduce in response to environmental stimuli such as a rise in water level and inundation of low-lying areas. These events do not occur in captivity and several techniques have been developed to induce artificial spawning on fish farms.

In Bamenda, located in the western highlands of Cameroon, ponds of about 300 m? are filled with ±20 cm of water and stocked with 4 mature couple of Clarias gariepinus (250–450 g weight) for 2–4 days in April (i.e. early rainy season). Water level is then increased up to 60 cm (artificial flooding) by early afternoon and spawning usually occurs at night. The number of fingerlings harvested 4–6 weeks later per kilogram female brooder is <400 and average weight is 5 grams. This is a rather poor outcome.

In one hatchery at Foreke, 10 kilometres from Santchou, hormone treatment is employed to ensure large-scale production of catfish fingerlings. Hormones used include Deoxycorticosterone Acetate (DOCA), Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (HCG), Luteinizing Hormon Releasing Hormone Analogue (LHRH-A) or pituitary glands from a catfish brooder, common carp, Nile tilapia and even frogs following specific technical procedures (De Graaf and Janssen, 1996; Pouomogne, Nana and Pouomogne, 1998). These procedures include hormone preparation, injection and stripping of the eggs from females following a precise time interval. Protecting the pond from predators is a key parameter in the survival of the fingerlings. In a well managed pond, over 20 000 fingerlings can be produced, with an average weight of 5 g per kilogram/female brooder. Although the procedures are being simplified, only a few farmers have been exposed to them. However, with the support of the WorldFish Center and the Institut de Recherche Agricole pour le Developpement (IRAD), a larger number of farmers are being trained in these techniques (Nguenga and Pouomogne, 2006; Sulem et al., 2007).

For fish farming to develop sustainably in Cameroon, catfish fingerlings need to be available at less than US$0.1/unit compared to the current US$0.15–0.25 price. The seasonal availability of natural fingerlings in the Nkam Valley is certainly an economically viable source of fingerlings; however such resource needs to be sustainably managed.

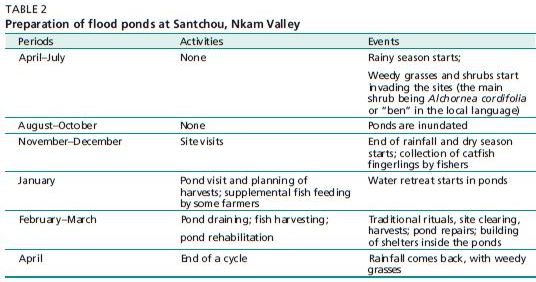

For the flood ponds in the Nkam Valley, pond preparation is performed just after harvesting in January–March at the end of the dry season, with the extraction of the bottom mud and rehabilitation of the fish shelters (Hem and Avit, 1994). Sunshine stimulates natural productivity before the start of the next rainy season in early April (Table 2). In normal years, flooding of the Nkam River and its tributaries occurs in July–October. Flood ponds are inundated at that time and fish recruit naturally to find the necessary food and shelter. Depending upon the severity of drying between rainy seasons, pond productivity may rise for 1 to 3 years before the pond is actually harvested.

TABLE 2

Preparation of flood ponds at Santchou, Nkam Valley

Source: Translated from Mfossa, 2007.

The collection of catfish fingerlings from fishing grounds (as opposed to flood ponds) begins in early December with the start of water retreat. The majority of the fish caught are sold for non flood pond stocking in the highlands or for consumption; some fishers may however add fingerlings to their flood ponds periodically. In this case, farmers provide supplemental feeding with table scraps. Average pond size and depth in Santchou valley are 40 m? (475 ponds, range 2–240 m?) and 1.7 m (range 0.5 to 3 m), respectively. Stocking occurs via natural recruitment during the annual pond flooding. Most ponds are harvested after a one-year rearing cycle (52 percent) or after 2 years (45 percent). Exceptionally high productions is sometimes recorded at up to 860 kg per 100 m? flood pond per year.