SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF FARMING

In each Santchou extended fishing family there are an average of five fingerling collectors and two flood pond fish farmers. The collection of juvenile catfish constitutes a marginal occupation; however, 50 percent of fishers have links with fish farmers outside of the valley and derive substantial income from selling fingerlings. Tradition and pleasure were stated as the motivations for being involved in fingerling collection or fish farming.

Besides fishing, farmers engage in other economic activities such as crop production, animal husbandry, trading and teaching. Fingerling collection and fish harvesting are performed during the dry season (November–March) along with cocoa and coffee harvesting and farm land preparation. Fishing and aquaculture activities are thus a secondary occupation after agriculture and land animal husbandry.

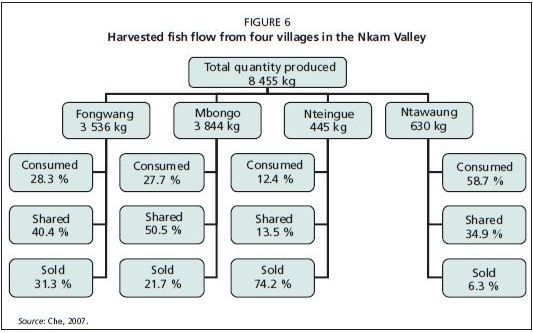

Most fishers are male (>85 percent), literate (>75 percent attended primary school), and married (70 percent), with an average of eight people living in the house. Che (2007) documented catfish production from flood ponds in several villages in the Nkam Valley in 2006. The total quantity harvested was 8 455 kilograms which were used as follows (Figure 6):

• direct consumption by the family (31 percent);

• gifts to relatives and friends (34 percent); and

• sale on the market (35 percent).

According to fishers, fish constitutes a major source of protein for the family. Sharing the catch with relative promotes love and friendship among the farmers. Selling

Capture-based aquaculture of clarias catfish: case study of the santchou fishers in western Cameroon 103

Figure 6

Harvested fish flow from four villages in the Nkam Valley

fish for cash increases household incomes and serves to help satisfy demand from other consumers.

Before the emergence of a market for fingerlings outside of the valley, fish were caught for bait, stocking of flood ponds or for direct human consumption. Fish in excess of what could be immediately consumed were often smoked for later utilization. Juveniles were often sold as human food at an estimated price of US$0.8 per kilogram fresh weight fish. At 25 grams average weight, this is equivalent to US$0.02 per fingerling.

With the competition introduced by outside buyers, the unit price is currently much higher (up to US$0.25 for Clarias gariepinus). Catfish collectors and dealers are being requested to separate the two catfish species (and to select Clarias gariepinus); to grade fish into homogenous sizes; to improve live fish handling and transportation techniques; and to hold fingerlings for sale outside of the wild-capture season. Since the literacy level among fishers is good, most of these challenges are likely to be met.

Traditional annual festivities are organized to pay tribute to the gods of the valley who benevolently provide fishery resources to the Mbo. This special relationship with their gods strongly encourages the Mbo to protect the aquatic environment, limiting catches and designating certain areas within the valley as sacred and not to be fished or farmed.

To address the market demands mentioned above, fishers have gathered into groups and requested technical and financial support from the authorities and from the donor community. One of the activities of the CIP project (see Annex 1) is to train farmers to increase their profitability from the fishing activity. One group of farmer groups (Pecheurs Et Pisciculteurs De Santchou – PEPISA), has recently overseen the training of six fingerling collectors who are now capable of sorting fish into species and sizes classes.

The case study of four villages illustrates the social issues and income generated from the Clarias fishery in the Nkam Valley (Che, 2007):

i) One of the objectives of the fish farmers in these villages is to have good quality fresh fish for home consumption. The fish consumed by an average fish farmer is almost 10 times the maximum quantity consumed by rural fish farmers in Yaounde (8.3 kg) (Brummett, 2005; Brummett, Pouomogne and Gokowsky, 2007). The total annual fish consumed in the villages has been estimated at >30 percent of the total quantity of fish produced.

Figure 7

Sale of fresh catfish at home (left) or ready for smoking (right)

ii) An important part of the fish produced is donated as gifts (34 percent). Fishers explain that sharing strengthens relationships between friends and family members. In Santchou, the fish are shared either fresh (10 percent) or smoked (90 percent).

iii) The selling of fish immediately after harvest is either at the fish farmer’s house (>57 percent) (Figure 7), along the road (24 percent) or at the market. Information concerning the harvest and selling of fish is usually communicated verbally to friends and neighbours and to more distant households by sending children with fish to circulate in the area so that people will see and ask where they can buy more. Some of these buyers place their orders before the farmer harvests the fish. In case the fish destined for sale is not all purchased, the remaining fish are prepared for preservation through smoking. The buyers of the fish are restaurant owners, mostly women, retailers and housewives.

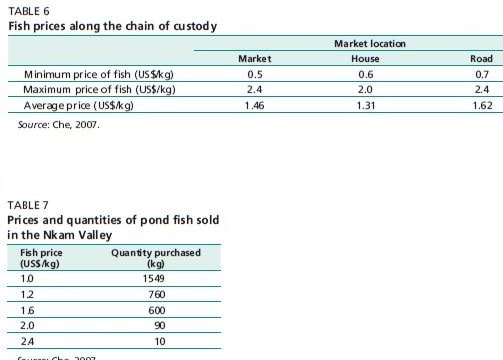

Over 28 percent of fish farmers sell fish on a weighing scale, while most sell the fish in heaps or strung on ropes. The prices of fish currently vary between US$1.00 and US$2.4 per kilogram (Table 6).

TABLE 6

Fish prices along the chain of custody

TABLE 7

Prices and quantities of pond fish sold in the Nkam Valley

Source: Che, 2007.

The price for pond fish ranges from US$1.0 to 1.6 per kilogram, with most purchased at the lower end of the scale (Table 7). Demand is thus relatively inelastic as fish are perceived as an inferior good, which is mainly consumed in low income households. The average price of fish is higher when it is sold along the road in comparison to those sold in the farmer’s house or at the market.

Over the four month season, an individual fingerling collector distributes an average of 11 700 juveniles for a total revenue of US$1 630.

Although fish collection is a seasonal and secondary activity, after agriculture and animal

Capture-based aquaculture of clarias catfish: case study of the santchou fishers in western Cameroon 105

husbandry, it can be economically attractive compared to other activities if sustainability managed. Expectations of the farmers are high particularly if they receive training on how best to keep juvenile Clarias alive to supply buyers outside the fishing season.