SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF EEL FARMING

Social impacts

From fisherman to consumer

In France, approximately 1 300 professional fishers are directly involved in glass eel harvesting in marine and continental waters (Castelnaud et al., 2005). A leisure fishery also exists, but the sale of the eels is forbidden. Illegal fishing is an important problem on some estuaries, e.g. the Gironde and Loire. Illegal catches are difficult to estimate, but could be of the same order as the legal catch on some rivers.

In England, the glass eel harvest requires a licence that costs ?63 (approximately US$126) and in 2005 805 fishers held a licence (Pawson et al., 2005). Fishing is only allowed using handheld dipnets. In Spain, around 682 fishers harvest glass eels in the Basque country (Diaz and Castellanos, 2005). These fishers are not considered professional, but are authorized to sell their catch. In Asturias, on the Nalon River, there are about 50 eel boats licences for boat fishing and between 150 and 200 fishing licences for land-based operations. On the Esva River, there is also a professional land

based fishery, but the number of fishers is not recorded (Garcia-Florez, Herrero and de la Hoz Reguls, 2005). Eel fishing exists also in the Guadalquivir (Sobrinho et al., 2005) in Andalucia, but the fishing effort and the catch have not been quantified. On the Mediterranean coast, a small fishery also exists on the estuary of the Ebro River in Catalonia (Spain).

In Portugal, glass eel harvest was banned in 2000, except in the Minho River on the boarder between Spain and Portugal (Coimbra et al., 2005). However, the activity still continues to some degree as “Portuguese glass eels” are often available on the market. In Italy the number of licences is difficult to assess because there is no central registration (Ciccotti, 2005). There are possibly around 10 companies fishing glass eels in marine waters.

In Morocco the eels are collected using large traps that stretch across the river. There are 200 to 300 fishers collecting glass eel, and the activity supports the livelihoods of at least double this number. The total quantity of eels collected per season is around 3 tonnes, but due to poor conditions and materials used, only 1/3 usually survive following collection. All the fish are exported despite a national regulation stipulating that 75 percent of the glass eel harvested in Morocco are to be farmed locally.

The total number of eel fishers in Europe is estimated to be between 3 000–3 500, mainly in France, United Kingdom and Spain. The European eel fishers sell their catch to middlemen, of which there are around 80–100. Wholesalers purchase the fish from the middlemen and then place glass eel batches of 80–500 kilograms on the market as buyers are not interested in batches <80 kilograms.

In order to deliver glass eels to the European farmers and to the Asian importers, the suppliers need to run a fleet of transport trucks, have skilled workers and funds to purchase the glass eels. Only larger companies are able to assemble these means. There are 8 wholesalers in Spain, 9 in France and 2 in the United Kingdom. Wholesalers employ between 2–15 persons, and are often family-based companies. Some companies only work with glass eels, while others also trade in all sorts of seafood. The glass eel fishery alone engages around 3 300–3 900 people, not including those working in the aquaculture sector.

There are approximately 50 eel farms in Europe (26 in the Netherlands, 8 in Denmark, 3 in Germany, 4 in Spain, 2 in the United Kingdom, 2 in Sweden and 2–3 in Eastern Europe) and around 1 000 farms in Asia raising the European eel. In Europe, most farms sell their product to eel traders, mainly from the Netherlands as the size of the eels (i.e. 130/150 g) best match the Dutch market. Smaller farms sell all or part of their production directly to customers, as live, fresh and gutted, or as smoked, and obtain a better price for their product. The traders buy several tonnes from the farmers, grade the fish, sell the larger ones to Denmark or Germany, and the rest is smoked for the Dutch customers and sold as whole smoked eels or filleted smoked eel. In China, the domestic demand for the end product is growing but currently only a small fraction of the production is sold locally. Most eels are exported, with Japan importing almost 80 percent of the production. The eels are exported live, gutted and frozen or prepared as kabayaki in China-based processing plants. The eels shipped to Japan undergo a severe health and quality inspection for possible contaminants and prohibited products before being allowed to enter the country.

The eel fishers are nearly all men, usually assisted by their wives or other family members. In France, they need to hold a “Capacity Certificate”, be 18 years old and have acquired at least 12 months work experience on board of a fishing boat. French glass eel fishers make a good living and generate almost 90 percent of their annual income. The eel wholesalers in France are mostly based in the Basque country where most of the eel are traditionally sold to Spain. The number of companies trading eel is decreasing as the market is very competitive and many small family-size companies are unable to cater for the Chinese market.

Aquaculture impact on the eel market

Until 1985, glass eels were either used for direct human consumption or for restocking programmes. Supplies were so plentiful that in the early twentieth century the eel fry were fed to poultry and used to produce glue. Whole train wagons of glass eels destined for Spain were typically loaded in Nantes, France, with 50 kilogram jute bags of eels. The main source of glass eels was France and the fish were caught and collected around the main estuaries of the Atlantic coast and transported by trucks to holding stations along the French/Spanish border. When conditions were favourable, the trucks were reloaded to deliver the fish to processing facilities mainly located in the village of Aginaga in Spain.

From 1985 to 1993, European eel farmers purchased about 10 percent of the glass eels collected without affecting the overall market price of the commodity. The average price during this period was €40/kg (approximately US$63/kg) although adverse climatic events and festivities such as Christmas, New Year and San Sebastian day affect the price of the glass eels. Only few people or suppliers were interested in the aquaculture market for glass eel and supplied the European farmers during this period.

In 1993 China started to purchase the European glass eel (Anguilla anguilla) because the supply of the local Anguilla japonica was insufficient and prices had risen considerably. From 1993 to 2006 the average price was €300/kg (approximately US$474), with peaks of €1 150/kg (approximately US$1 816). The European glass eel traders could no longer ignore the demand generated by the aquaculture sector which was ready to pay much higher prices. The cooked eel market could not afford such prices and was only supplied with poor quality eel or the dead eel.

In the early 1990s the overall eel market for human consumption became very weak, and many eel farms in Europe and Asia were forced to shut down. A further crisis occurred in the 1998/1999 season when large quantities of farmed Chinese eels, following the imports of 200 tonnes of glass eels in 1996, flooded the market causing the eel price to drop by 50 percent. This resulted in the closure of additional eel farms throughout the producing nations. In the 2003/2004 season the Chinese industry somewhat recovered due to the lack of both Anguilla anguilla and Anguilla japonica, and importers paid prices of up to €1 150/kilogram (approximately US$1 816) of glass eels.

Eel aquaculture has sustained a fishing industry that would probably have ceased to exist if it continued to be based only on the consumption market. With the pre 1985 prices of less than €40/kg (approximately US$63) and current quantities of approximately 150 tonnes per season, the glass eel fishery would not be economically viable. Price levels created by aquaculture demand maintain the fishery. The companies involved in the cooked eel industry have had to reduce their staff, or simply close down, while others started the production of glass eel surimi products.

The impact of farmed eels on wild-caught eels arises because Dutch traders pay a higher price for farmed eels than wild eels. The farmed eels are in fact more suitable for the smoking industry due to the higher fat content, standard sizes, year-round availability, regular supplies and do not have the typical “muddy” taste which is often the case in wild fish. Furthermore, wild eels are also more susceptible to stress, often damaged following fishing (tail damage, mouth damage, etc.) and may experience high mortalities during transportation, grading or storage.

Employment and skill issues

Eel farming has generated new employment opportunities in Europe, but on a limited scale, as the farming technology used does not require a large team of workers and technicians. In the European smoked fish processing sector the farmed eel replaced the wild eel and therefore no major employment changes occurred. On the other hand eel farming in Asia has created significant employment in both the farming and processing sectors (Figure 11).

The transition of the fishing industry to eel aquaculture did not much affect the fishers as the final market destination of the glass eels simply changed, with buyers mainly from the farms rather than the processing plants. However, the shortage of glass eels brought about the banning of non-professional harvesters (e.g. in France) and forced many out of the fishery.

With aquaculture now so critical to this industry, the quality of the glass eels harvested and a reduction of eel mortality is of utmost importance. In spite of this, only few of the French fishers have really made an effort to supply better quality fish to the riverbank middlemen. Most of them are only concerned by the quantity of fish collected, rather than quality. If there was a real price difference between dead and live fish, or even between good and bad quality, the fishers would quickly react to this. The laws regulating the fishery including the net size and boat engine permitted are not adequately enforced.

Economic issues

Market evolution

Eel fishers can be considered as the main beneficiaries of the development of eel aquaculture activity. Without this evolution, the glass eel fishery would have become uneconomical and would

FIGURE 11

Workers in a Kabayaki factory gutting and preparing the eels

probably have ended. The fishery is in fact sustainable only if the price per kilogram of eel is higher than €200 (approximately US$316). As the price per kilogram increased considerably due to the demand from the aquaculture sector most of the estuarine and fluvial fishers are making a decent living. Out of the approximately 15 major wholesalers before aquaculture took over the market, 7 have completely stopped trading glass eel or do not exist any longer, 5 have lost market share, and 3 are performing well. Three new companies have started exclusively based on supplying the aquaculture market.

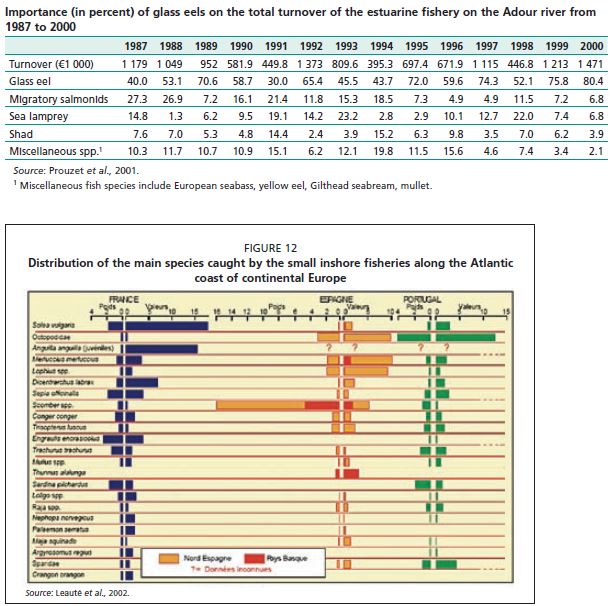

TABLE 5

Importance (in percent) of glass eels on the total turnover of the estuarine fishery on the Adour river from 1987 to 2000

Source: Prouzet et al., 2001.

1 Miscellaneous fish species include European seabass, yellow eel, Gilthead seabream, mullet.

FIGURE 12

Distribution of the main species caught by the small inshore fisheries along the Atlantic coast of continental Europe

Source: Leaute et al., 2002.

Economic dependence of the small-scale fisheries

The eel fishing activity is conducted by different groups of fishers generally carrying out also other fishery-related activities such as oyster farming or sea fishing. Nevertheless, the small-scale glass eel fishery constitutes a major economic activity for most of the fishers involved as demonstrated by the Adour River (Table 5). On a larger scale, the EU project on the “Caracteristiques des petites peches cotieres et estuariennes de la cote atlantique du sud de l’Europe” (Peches Cotieres et Estuariennes du Sud de l’Europe – PECOSUDE) was undertaken to assess the economic impact of inshore and estuarine fisheries from the Loire estuary (France) all the way to the south of Portugal (Leaute, 2002). Among the 200 identified species or group of species landed along the investigated area, 7 species represented almost 53 percent of the total value in 1999. Of these, the European eel (especially the glass eel stage) ranked second in value along the French coast (Figure 12).