FISHERIES FOR JUVENILE GROUPER

Collection of grouper seed

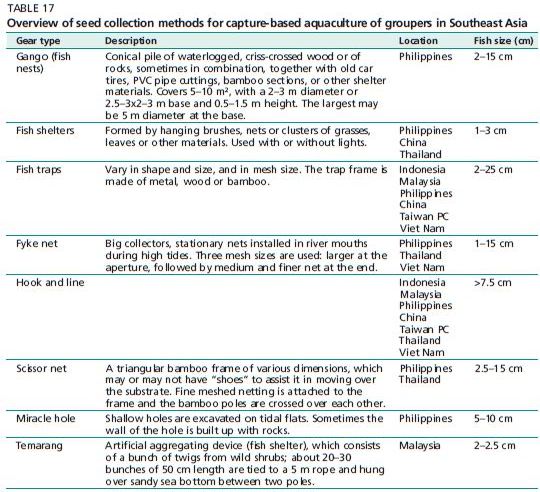

Grouper seed is collected using several different methods, depending on location (Table 17). Capture methods are generally artisanal and the fishermen employ a variety of artificial habitats. Moreover, different fishing gears are used at different times of the year: the gear change follows the growth of the seed and their movement to deeper waters as the season progresses. Gears used to take grouper seed can be divided into 8 different categories: large fixed nets (e.g. fyke nets), traps and shelters, hook and line, scoop and push nets, artificial reefs, fish attractors, tidal pools and chemicals.

The sizes of grouper seed caught and traded vary between 1 and 25 cm, i.e. from the moment of settlement to fish that are over one year old. However, most of the catch focuses on fish up to about 15 cm (Sadovy, 2000).

Some grouper seed collection methods are more damaging than others. Clearly destructive methods include those that result in high mortality, involve high levels of

TABLE 17

Overview of seed collection methods for capture-based aquaculture of groupers in Southeast Asia Gear type Description Location Fish size (cm)

bycatch, cause damage to the fish habitat and/or result in monopolization of the local fishery by a few individuals. Destructive methods include scissor nets and fyke nets, which are already banned in some areas. Lift nets are also destructive, particularly in terms of bycatch. Gangos, miracle holes and other types of artificial shelters and seed aggregation devices do not possess the above drawbacks. Methods that target postlarvae seem less likely to deplete wild stocks because of the high natural mortality that probably characterizes this stage in the wild (Johannes and Ogburn, 1999; Sadovy, 2000).

Mortality rates from catching to stocking

Seed quality depends on the type of fishing gears used, and there are significant differences in seed mortality rates. Mortality rates associated with fish traps are usually low. For example, the use of “Bubu” (fish traps used in Malaysia) cause a 5 percent mortality rate, while artificial aggregators such as Temarang (also used in Malaysia) cause 3 percent mortality. Other catching methods, like scissor nets and fyke nets, can generate a high mortality. “Pompang” (fyke net) and “Wunron” (push/scissor net), which are used in Thailand, are reported to cause 20–30 percent and 80 percent mortality rates, respectively (Sadovy, 2000). It is likely that subsequent mortalities during transport and stocking will also be high, as many of the seed fish will also have been damaged, and are therefore susceptible to stress and disease.

The problems that arise during seed transport to the net cages or to the middleman/ farmer/exporter, depend on seed size, quality, fitness and the locality. For transport over short distances, in Thailand, for example, “seeds” are placed in styrofoam boxes or buckets, with or without aeration (often provided by middlemen), or with holes in the bottom for water exchange.

Transport time is typically from about 10 minutes up to two hours. Post-harvest mortality is low. For longer transit periods, fish are packed in 23–25°C seawater with aeration. Transport densities are about fifty 7.5 cm fish per bag, or one hundred 1 cm fish/l, or two to three hundred 3–7.5 cm fish per bucket. For a 7-hour journey, ice can be used to keep the water cool. Some exporters use an anaesthetic, either quinaldine or MS222, but consider the latter to be rather expensive. The use of anaesthetic is considered important to reduce the likelihood of spines piercing the plastic transport bag. For export, fish are packed into styrofoam boxes of various sizes; each shipment has about 20 000 fish in 30 boxes (Sadovy, 2000).

In the Philippines, approximately 10 percent of the seed caught is used domestically, while the remainder is exported. There can be significant mortalities during local transportation. The movement of seed from the catchers to the middlemen or the farmers is carried out by keeping fish in plastic containers or basins with holes for water circulation. Mortality rates are quite low under such circumstances. If destined for trade, the fish may be maintained for short periods by the middleman, prior to packing and shipping, either domestically or internationally. In some cases, they may be transferred temporarily (for a few days) to an “aquarium box” to await buyers who come to collect fish and who are responsible for the export of the fry. Mortality rates can reach 10–20 percent at this stage, i.e. prior to selling to buyers for export or domestic trade (Sadovy, 2000). Mortality rates are low if the transit time is less than an hour. However, for longer periods, if there is no aeration or frequent water changes, mortality increases and oxygen may have to be added. Buyers pack fry in double plastic bags with pre-cooled water using ice (18–22°C) and a salinity of 15–18 ppt. 2.5 cm “seeds” are packed 400–500 per box and 7.5–10 cm “seeds” are packed 20–40 per box (Sadovy, 2000).

The mortality rates that follow capture and transport are not exactly known; estimates for over the first 2 months after catching are quite variable (30–70 percent), depending on the quality of fry, the level of transport stress, and the presence of disease and cannibalism (Pudadera, Hamid and Yusof, 2002). According to a report from the Secretariat of the Pacific Community (www.spc.org.nc/coastfish/ News/LRF/5/15GrouperHK.htm), the survival rate for imported fry is low, at 10–20 percent.