SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF GROUPER FARMING

Despite the growing importance of grouper aquaculture as both an alternative to wild caught grouper for the LRFT, and as an alternative livelihood for fishers engaged in destructive fishing practices, relatively little is known about the social and economic impacts of grouper farming, and the broader socio-economic context in which it takes place. Studies have focused on the trade of live reef fish which fuels the fishery for grouper and provides an incentive for grouper aquaculture.

The trade in live reef fish

The trade in live reef fish, whereby fish are transported live from the capture location to restaurants and supermarkets, began in China in the 1960s when a few marine species were to be found in the live fish markets of China Hong Kong SAR, and has expanded rapidly since the early 1990s. The preference for keeping fish alive until minutes before cooking and consumption has been popular for centuries in Chinese culture, and until recently this demand for live fish was supplied by locally caught species. A preferred species for consumption was the red grouper, Epinephalus akaara, until overfishing of both adults and later fingerlings for culture in China Hong Kong SAR waters led to severe depletion of local stocks, forcing fishermen and the LRFT industry further afield to seek out supplies to meet local demand for market size fish. In the mid-1970s fishing boats began to exploit Philippine waters, and later the islands of Indonesia, before moving on to the Pacific Islands (e.g. Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands), Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, and the Maldives (Johannes and Riepen, 1995). Thailand is now also an important contributor to the LRFT. The trade supplies a luxury, niche market. Live reef fish are described as being “high-value-to-volume” and can fetch US$5 to US$180 per kilogram, considerably more than dead reef fish (Sadovy et al., 2003). Highly valued species such as Cheilinus undulatus, or humphead wrasse, can fetch a price of up to US$200 per kilogram (Lau and Parry-Jones, 1999).

China Hong Kong SAR is the hub of the live reef fish trade, and the destination for much of the wild-caught and cultured grouper in the region. Approximately 60 percent of internationally traded live reef fish are exported to China Hong Kong SAR (Sadovy and Vincent, 2002), representing approximately 15 000 to 20 000 tonnes per year at a value of US$350 million (Muldoon and MacGilvray, 2004). Accurate volumes of trade for individual species are difficult to estimate, as exports are not disaggregated at the species level and much of the trade goes unreported (Sadovy et al., 2003).

The market network linking farmers to consumers is relatively long and complex, frequently crossing international boundaries, with ownership changing repeatedly. Grouper farmers obtain fry fish from their own fish catch, purchase from local fry fishers, private or government hatcheries. It is common for fry fishers who do culture grouper to sell their catch to a middleman, who may support a group of ten to thirty fishers. The fry are then either sold locally to farmers for on-growing or transported directly to export centres for shipping to other countries in the region. Grouper from grow-out operations are also predominantly destined for the export market, although there is also a growing domestic market in many countries where grouper are becoming increasingly popular on the menus of local seafood restaurants throughout Southeast Asia.

Social impact of grouper fry fishing

The number of fishers exploiting the grouper fry resource is unknown, but estimates suggest that fry fishers in the Philippines may number in the tens of thousands (Sadovy, 2000). For these fishers, fry fishing represents one activity in a broader portfolio of activities on which they depend. Fry fishing is seasonal in nature and both fishers and non-fishers alike enter the fry fishery if market signals indicate a lucrative opportunity. Fishers may be engaged in the fishery on a full- or part-time basis, whilst also engaging in other fishing activities for the capture of food fish or fish for the aquarium trade (Sadovy, 2000). The capture of wild grouper fry is reported to make a significant economic contribution to the lives of coastal fishers (Sadovy, 2000). However, despite this apparent significance, few studies have attempted to assess the role of these wild fry fisheries in the livelihoods of coastal fishers. There is, therefore, a critical gap in our understanding of the precise nature of the contribution made by wild fry fisheries to coastal households, the economic and gender profile of fishers, and the way in which coastal fishers may be affected by developments in the grouper industry.

Some studies in the region do indicate that the capture of grouper fry may contribute substantially to household incomes. In Sulawesi, Indonesia, for example, fishers may catch in the region of 1 000–2 000 2.5 cm fry per fisher on daily basis during the peak season using scoop nets, with a value of US$300–600 (Haylor et al., 2003). In Viet Nam, income from grouper fry/fingerling harvest was reported to earn fishers as much as US$3 080 per year (Sadovy, 2000).

Grouper fry fishers do not represent a homogenous group in terms of social status. Fishing households, like most rural households, engage in a diverse range of activities of which fishing may be only one component. Similarly, fishing activities are also diverse with fishers using a variety of gears to target different species according to seasonality and the tides. Dependence upon fry fishing is therefore rare, if it exists at all, although the extent to which the income from fry capture contributes to the total household income will vary from household to household. The relatively high value of grouper fry compared to the rest of the fish catch may, therefore, represent an important income source. As one fisher in Viet Nam indicated, catching 5–10 grouper fry per day can equal the income from all the other fish harvested (Sadovy, 2000). Findings from a survey in Thailand suggest that, for the majority of households, fry fishing is a supplementary activity, often opportunistic, with fishers entering and leaving the fishery according to fry abundance and market signals. Fry fishing in southern Thailand complements the regular fishing activities of coastal fishers, whose principal target species, including shrimp, small pelagic species, are caught at different times of the lunar calendar. Fry fishing therefore allows fishers to supplement their fishing activities at a time when fishing would otherwise not be possible (Sheriff, 2004).

Social impacts of grouper aquaculture

Important synergies exist between grouper aquaculture and fry fishing, which blur the distinction between fry fishers and grouper farmers, and give added significance to the role of grouper fry in coastal livelihoods. In the absence of a reliable source of hatchery fry, and the preference of many farmers for wild caught fry even where hatchery fry is available, most grouper farmers rely upon wild-caught fry to stock their culture systems. Where adequate supplies of grouper fry are still available in the wild, many farmers fish for their own seed inputs which, as they are not purchased and require no cash outlay, are considered a “free” resource. This has important implications for the ability of resource poor households, with little access to financial capital, to take up grouper aquaculture.

Grouper aquaculture has been identified as an activity which can generate a relatively high return in comparison to many of activities available to coastal households (Hambrey, Tuan and Thuong, 2001). Many activities which generate a comparable return, including trading, ownership of plantations and shrimp culture are inaccessible to the majority of households due to the high levels of investment required to take up these activities. Grouper aquaculture can therefore be an important addition to household livelihoods, providing a means of savings to supplement the daily income generated by regular fishing activities (Sheriff, 2004).

As a solution to the problem of destructive fishing, aquaculture may not present the ideal alternative to fishing, as is frequently suggested. There is an assumption that aquaculture is an activity that is easily interchangeable with fishing as a livelihood activity, and that fishers are willing and able to give up fishing to take up a new and markedly different occupation. Studies suggest that fishing is deeply rooted in the lives and traditions of “fishing” communities and the identity of fishers. McGoodwin (2001) reports that fishing is regarded “not merely as a means of ensuring their livelihoods, but as an intrinsically rewarding activity in its own right – as a desirable and meaningful way of spending one’s life…prompting many fishers to tenaciously adhere to the occupation and to continue fishing even after it has become economically unrewarding.” In a study conducted by Pollnac, Pomeroy and Harkes (2001) in the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia, it was found that, in all three countries, fishers like their occupation and only a minority would change to another occupation, with a similar income, if it were available. In the Philippines, 95 percent of fishers surveyed reported that they would choose to become fishers again if they had to live their life over again. They also cited pleasurable aspects of the job as reasons for staying in the fishery, including the beauty of the sea and not having to work for a boss. Fishers in the three countries who would choose to leave the fishery were characterized by a higher level of education and a lower income from fishing. The results do not support the view that fishers are the poorest of the poor, as fishers cite income as one of the reasons for choosing not to change their occupation. The level of satisfaction with fishing as an occupation suggests that fishers will not necessarily change to an alternative occupation and leave the fishery (Pollnac, Pomeroy and Harkes, 2001). Furthermore, the role of fishing in households livelihoods differs markedly from the contribution made by aquaculture. Fishing provides a source of daily income which pays for the daily needs of the household. In contrast, fish culture has been identified as being of importance to the households ability to save money and thus to accumulate assets. Proposals to encourage fishers to leave the fishery by offering fish culture as an alternative, may therefore fail, as fish culture cannot meet the daily needs of the household. Aquaculture can, however, provide an important supplementary activity to support livelihood diversification in coastal communities, where few alternatives may exist (Sheriff, 2004).

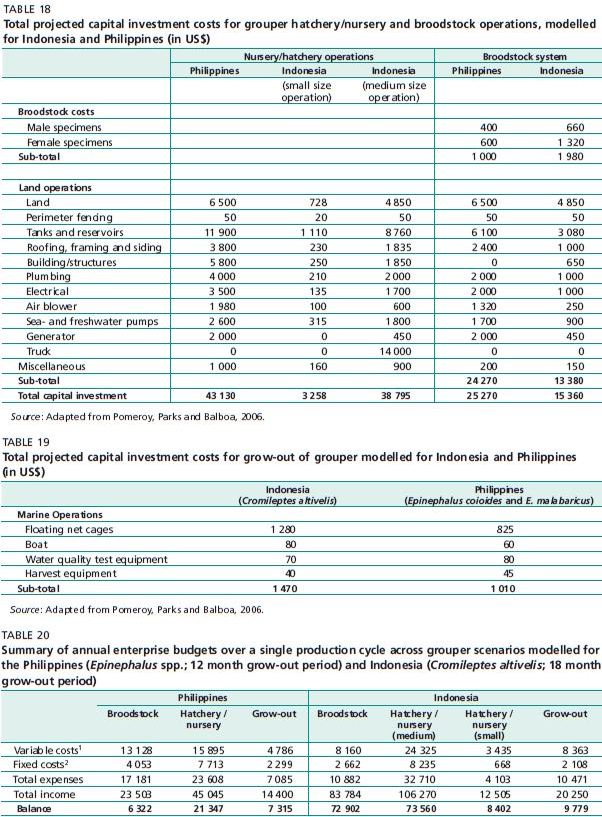

As a contributor to rural livelihoods, particularly those of coastal fishers, grouper aquaculture can generate potentially large financial benefits. The high-value of grouper on the export market ensures that farmers are able to generate a profit even when stocks suffer heavy mortalities. High initial investment cost is frequently cited as the principal constraint to the uptake of grouper aquaculture. Approximate investment costs for a small-scale farm are in the region of US$1 470 in the Philippines and US$1 010 in Indonesia (Pomeroy, Parks and Balboa, 2006), US$516 in Viet Nam (Hambrey, Tuan and Thuong, 2001) and US$237 in Thailand (Sheriff, 2004). Financial analyses of grouper aquaculture have indicated that grouper rearing is financially feasible, although Pomeroy, Parks and Balboa (2006) found that the capital requirements of some aquaculture systems in the Philippines and Indonesia may be beyond the financial means of many small producers, specifically broodstock and nursery/hatchery systems (Table 18). However, capital costs for grow-out are substantially lower than the broodstock or nursery systems, and are within the financial means of many small producers (Pomeroy, Parks and Balboa, 2006) (Table 19). This figure excludes holding tanks, and therefore more accurately reflects reality. Fish are most frequently kept in holding tanks of a local fish trader within the community, and therefore represent a cost which will not often be incurred at the farm level. The total production costs per market size fish from grow-out, US$3.01 in the Philippines and US$3.18 in Indonesia for a 600 g fish, were found to be well below the average selling price at the time of the Pomeroy, Parks and Balboa (2006) study, which was US$6 in 2002. With the sale of market size fish able to generate this level of profit, it is not surprising to find that the annual enterprise budget show in Table 20 suggests that the cost of investment can be recouped relatively quickly. Pomeroy, Parks and Balboa (2006) conclude from their analysis that loans or other incentives to cover start-up costs could be repaid within the first or second year of production.

Despite these apparently high costs studies have shown that, with appropriate support, even the poorest can benefit from grouper culture, with implications for both household well-being and community development. For example, one study in Thailand found that grouper culture was taken up by households from all wealth groups within a community in Satun province (Sheriff et al., in press). Support from the Thai Department of Fisheries in the form of materials for cage construction and seabass seed allowed households to establish a small farm of two cages with which to initiate grouper culture. Grouper fry were supplied in small quantities from the farmers fish catch, and a share of the profits returned to a centralized revolving fund for the benefit of all households in the community.

TABLE 18

Total projected capital investment costs for grouper hatchery/nursery and broodstock operations, modelled for Indonesia and Philippines (in US$)

Source: Adapted from Pomeroy, Parks and Balboa, 2006.

TABLE 19

Total projected capital investment costs for grow-out of grouper modelled for Indonesia and Philippines (in US$)

Source: Adapted from Pomeroy, Parks and Balboa, 2006.

TABLE 20

Summary of annual enterprise budgets over a single production cycle across grouper scenarios modelled for the Philippines (Epinephalus spp.; 12 month grow-out period) and Indonesia (Cromileptes altivelis; 18 month grow-out period)

Philippines Indonesia

Source: Adapted from Pomeroy, Parks and Balboa, 2006.

1 Eggs, fingerlings, feed, vitamins/medication, chemicals, electricity, labour and consultants, fuel and oil, marketing/packing/ harvesting, supplies, repairs.

2 Depreciation of fixed assets, interest payments.

The absence of large-scale production of grouper fry has ensured that production is kept primarily in the hands of small-scale, individual family owned operations (Hambrey et al., 2001; Sadovy, 2000; Sheriff, 2004), however some systems involve a large number of cages and off-shore systems are being tested in countries including Malaysia and Viet Nam (Kongkeo and Philipps, 2001). On-going research efforts are focusing on the hatchery production of the most vulnerable and commercially important grouper species in an attempt to reduce pressure on wild stocks. Yet there may be significant socio-economic impacts if hatchery production becomes commercially viable on a large-scale, and may threaten the livelihoods of both fry fishers and small scale grouper farmers. Taiwan Province of China is one of few countries to have a successful hatchery industry and may provide some insight into the potential impacts of hatchery produced grouper, where production has led to a marked effect on demand for grouper fry and a subsequent decline in seed prices. A reduction in the value of grouper is anticipated by exporters and importers as a result of increased production (Sadovy, 2001a). However, small-scale hatchery production of grouper has been found to be a viable livelihood option providing employment opportunities and rural livelihood diversification (Siar, Johnston and Sim, 2002). In Bali, where many such hatcheries have been established, milkfish fry production has provided the basis for diversification into grouper fry, and therefore provides a particularly relevant model for transfer to countries like the Philippines. However, uncertainties remain as to the acceptability of hatchery produced grouper fry to grouper farmers and the likely livelihood impact of hatchery production on fry fishers and the value of cultured grouper.

Gender roles in the grouper fry fishery and aquaculture

The specific role of women within the grouper fry capture fishery and trade network is little understood. Within the fisheries sector, women often play an important role in post-harvest activities, which are absent from the live fish trade. However, women frequently take responsibility for trade and financial matters, and in countries such as Thailand, it is not unusual to find that the main fish and fry trader within the community is female, although fish trading beyond the community is more frequently the domain of men (Sheriff, personal communication). Grouper culture can provide perhaps the most significant opportunities for women, who are often responsible for maintaining aquaculture operations on a daily basis (Haylor et al., 2003). The requirement for trash fish is high in grouper culture, and the preparation of trash fish for feeding is frequently done by women (Sheriff, 2004). Experience in Indonesia has shown that women may also find employment in the small-scale hatchery industry, providing labour as temporary workers for the counting and packaging of milkfish fry (earning in the region of US$0.33 per 5 000 fry counted), or as brokers in the fry marketing chain (Siar, Johnston and Sim, 2002). Similar work in a grouper hatchery grading grouper fry may earn women US$6.66 per day. The work is however, extremely hard, according to one hatchery owner (Siar, Johnston and Sim, 2002).