DESCRIPTION OF MUD CRABS AND THEIR USE IN AQUACULTURE

Species

There are four species of mud (or mangrove) crabs in the genus Scylla, S. serrata, S. olivacea, S. tranquebarica and S. paramamosain (Keenan, 1999b; Keenan, Davie

FIGURE 1

Juvenile mud crab

and Mann, 1998), all of which support capture fisheries and aquaculture. In most countries where mud crabs are fished or farmed, they are an important source of income from both export and local sales, and are utilized by recreational fishers.

Life cycle

All mud crabs commonly display 6 larval stages; 5 zoeal stages, followed by a megalops larval stage which precedes the first crab stage (Figure 1). Mud crabs typically undergo 14–16 moults prior to reaching their maximum size. Reported daily weight gain for mud crabs varies from 1–4 g per day and varies with species, and sex, with males reportedly growing faster than females (Trino, Millamena and Keenan, 1999b; Christensen, Macintosh and Phuong, 2004). All mud crabs can mature within their first year of life, with S. paramamosain maturing at a size of 102 mm carapace width at around 160 days from settlement (Le Vay, Ut and Walton, 2006; Le Vay, Ut and Walton, 2007), whilst S. serrata have reportedly grown to 750 g within 145 days and shown signs of maturity at day 147 (Field, 2006). They are highly fecund with individual females carrying over 3 million eggs. Apart from spawning migrations where females may travel considerable distances offshore most crabs appear to move little within their local habitat, which is typically mangrove forest (Hill, 1975; Hill, 1976; Le Vay, Ut and Walton, 2006; Le Vay, Ut and Walton, 2007). Mud crabs of different sizes occupy different niches within mangrove forests and the adjacent sub tidal zone (Walton et al., 2006).

Habitat

Mud crabs are a common component of the fauna of mangrove forests, usually burrowing in mud or sandy-muds. They have a diverse diet and are omnivorous in nature, feeding on a wide range of animal and plant resources (Hill, 1976).

Geographical distribution

The distribution of mud crabs extends from South Africa, along the southern coasts of middle-eastern countries, across the Indian Ocean and northerly to the southern tip of Japan, east as far as Micronesia and south to the east coast of Australia. Scylla serrata is the most widely distributed species, whilst Indonesia appears to be the centre of diversity for the genus, where all four species of Scylla are found.

Capture fishery

The mud crab is a targeted species for harvest across its range. Techniques vary from catching by hand to the use of fishing gear including tangle nets, baited traps and lift nets. Fishery trends for the last decade are detailed in Table 1. However it should be noted that figures for Sri Lanka and Australia were missing from the FAO database and not included here, so that these figures represent an underestimate of the production of

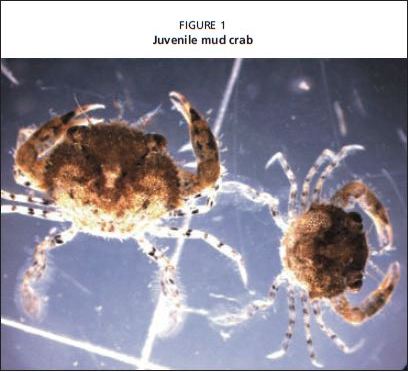

TABLE 1

Capture of Scylla serrata in tonnes

has shown an increasing catch, all other major producers have shown either a decreasing or static catch.

Harvest products

Juvenile crabs or crablets are actively harvested throughout Southeast Asia for use as seed stock for crab farms. Sizes harvested vary from a few centimetres across the carapace to just under harvest size for sale direct to market.

Crabs of close to, or at a marketable size are caught for a range of activities. Crabs which have recently moulted and have not fully grown to fill their new shells are commonly referred to as “empty” crabs. Such crabs may be put into fattening pens, ponds or enclosures and fed until they are “full” and ready for market.

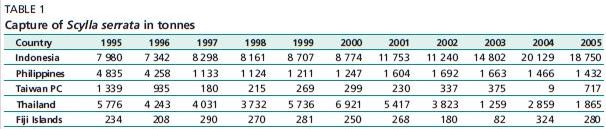

FIGURE 2

Live crabs on sale in Viet Nam

Other crabs of varying sizes will be caught and put into soft shell shedding facilities. Such crabs are commonly placed in individual containers and monitored until they moult. On moulting the crabs will either be chilled and put on ice, or frozen for the soft shell crab market, where all parts of the crab can be consumed as the shell has not been allowed to harden after moulting. Finally, hard-shell crabs of a marketable size are collected, secured to ensure traders and customers are not injured by their powerful claws and sold; most commonly in the live form (Figure 2). The size of crabs marketed varies with species. In the Philippines S. serrata is most commonly harvested at weights over 500 g, whilst for S. olivacea and S. tranquebarica the weight is usually over 350 g.

Whilst mud crabs are usually a targeted species, they may be caught occasionally in various nets which are targeting other mangrove or reef species and are caught as they move across their habitat. Only a very small part of the mud crab harvested is bycatch of other fisheries. Mud crabs adapt very well to a farmed environment. With their omnivorous diet they will eat a wide range of feeds, from trash fish through to pelletised aquaculture feeds.

There are a number of problems encountered by collectors and farmers, involved with using wild harvested crabs in various farming systems. Stock will often consist of a wide variety of sizes, and as mud crabs have a tendency to cannibalism, larger specimens will often predate on smaller crabs, causing significant mortalities amongst farm stock.

Life cycle status

Mud crabs born in captivity have been successfully mated with both wild and other captive stock so that some organizations and companies now use domesticated stock. Almost all hard shell, mature females collected from the wild will have been impregnated and will spawn if held under appropriate conditions. Each mature female will usually be able to spawn 2 or 3 batches of larvae when held under satisfactory conditions following a single copulation.

The use of farm produced seed is now becoming common in Viet Nam and China in particular. In some countries, such as the Philippines, there has been caution in the use of hatchery produced stock to date (Shelley, 2004a). Farmers have reported a range of concerns with crablets produced in hatcheries; will they be as robust as wild stock, will they grow as fast, will they be more prone to disease, and which is the better value for money – wild or farm produced stock?

In some countries where mud crab fisheries are actively managed e.g. Australia, crablets or under-size crabs cannot be legally harvested.

Farming techniques

Considerable efforts have been made over the last few decades to develop effective technology for mud crab aquaculture (Brick, 1974; Angell, 1992; Heasman and Fielder, 1983; Keenan and Blackshaw, 1999a; Anon., 2001; Anon., 2005; Shelley et al., In Press; Wang et al., 2005). A significant body of work on mud crab aquaculture is contained in a number of workshops, conference proceedings and review papers (Angell, 1992; Anon., 2001, 2005; Keenan and Blackshaw, 1999a). The successful development of techniques to support the mass culture of mud crab larvae in hatcheries drove the rapid expansion of mud crab farming in China during the 1990s, and its subsequent expansion, often in polyculture with shrimp, fish and algae (Wang et al., 2005). In China, in 2003, over 34 000 ha of culture area for mud crab produced just over 100 000 tonnes whilst over 79 000 tonnes were taken from the wild, making China the worlds largest producer of mud crabs (N. Zhou, Network of Aquaculture Centres in Asia Pacific, personal communication).

Until recently, larval production of mud crabs had been difficult with low and inconsistent quantities of crablets produced. However in recent years average survival rates have increased (Wang et al., 2005), and production of crablets for farms is now practised at a commercial scale in countries including Viet Nam, China, Philippines and Australia. Maintaining stable water quality conditions, minimising bacteria build

up and providing high quality feeds at appropriate densities have proven to be the key needs for successful larval production of mud crabs (Shelley et al., In Press). There are a range of nursery systems used to grow mud crabs from the late zoeal stages, through megalops to settlement and metamorphosis to crablet. A variety of tanks, ponds and hapa nets within ponds have been successfully used. A complex 3-dimensional habitat within such systems increases the densities which can be carried by any particular system. Suitable habitats include netting, plastic mesh and artificial sea grass. An appropriate temperature and salinity range is required in nursery systems to maximize survival (Ruscoe, Shelley and Williams, 2004).

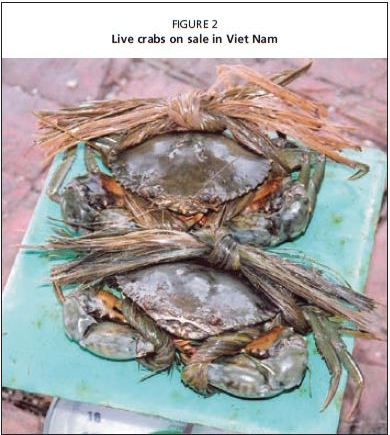

The grow-out of crabs is undertaken in various systems. The two major system types are: a) open; which includes ponds and mangrove enclosures where crabs are maintained at varying densities, and b) closed; where crabs are held in individual containers e.g. soft shell crab (Figures 3 and 4), or restrained in some way e.g. fattening enclosures (Figure 5). In Viet Nam culture techniques have been defined as extensive, intensive and cage culture (Thach, 2003). Crabs were fed on diets including trash fish, molluscs and small crustaceans. In extensive system seed crabs were stocked at 1 crab/5–10 m2 with wild seed, 1 crab/2–5 m2 for smaller hatchery seed, whilst an intensive stocking rate was considered to be 1–1.5 crabs/m2. Cage culture in Viet Nam is a fattening exercise where large crabs (200–400 g) are held in high densities of 35 crabs/m2 and fed until marketable. Lindner (2005) further described systems in Viet Nam, that included a range of low-input systems such as pens in mangrove forests and extensive shallow mangrove silviculture ponds that do not require supplemental feeding. In some areas in Viet Nam rice fields are flooded with brackish water that contains crab and/or shrimp seed, which become an important technique for farmers to supplement their income. More intensive Vietnamese systems that stock ponds at higher densities using purchased crablets commonly use trash fish or shellfish as feed and can produce 1–2.0 tonnes/ha-1/crop (Lindner, 2005).

In open production systems the cannibalistic behaviour of mud crabs is a major impediment to their high density production. Cannibalism can be minimized by using relatively low stocking densities and by utilizing some form of enclosures or shelter to provide refuge. Antagonistic behaviour between crabs can also result in loss of limbs by mud crabs. As a result, a percentage of crabs at harvest will have limbs missing and will fetch a lower price, or need to be kept longer on the farm for limbs to regenerate. To minimize the impact of cannibalism on survival a useful management strategy is to routinely undertake partial harvests of crabs (Say and Ikhwanuddin, 1999) of a commercial size in grow out systems, leaving sub-harvest size crabs to grow to harvest size with a reduced incidence of predation, in more space and with less competition for feed (Christensen, Macintosh and Phuong, 2004).

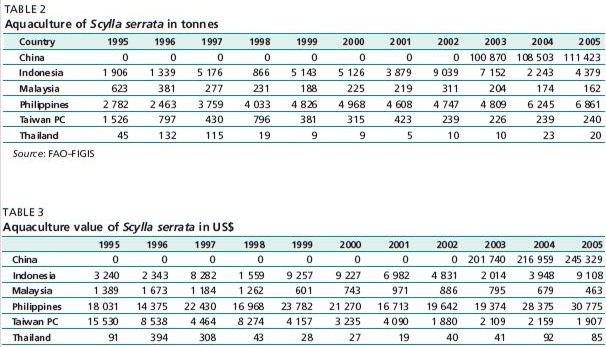

The statistics for aquaculture production of the mud crab (S.serrata) in Tables 2 and 3 indicate that in recent years Chinese production of mud crabs is approximately an order of magnitude greater than that of the next highest producing country

FIGURE 3

Mud crab fattening bamboo box in the Philippines

FIGURE 4

Mud crab individual fattening bamboo boxes in the Philippines

TABLE 2

Aquaculture of Scylla serrata in tonnes

TABLE 3

Aquaculture value of Scylla serrata in US$

(Viet Nam). In the last few years the Vietnamese production of farmed mud crabs has increased significantly, however statistics were not available from FAO for the country. It should also be noted that FAO statistics are nominally for S. serrata, however as three other species of mud crab are farmed in different countries it is believed that these figures are likely to more accurately represent production of the genus Scylla, rather than the species (S. serrata). These figures also demonstrate that the aquaculture production of mud crabs now exceeds that of wild harvest, notably because of the massive growth in the farming of mud crabs in China in recent years.

FIGURE 5

Mud crab fattening pen in Indonesia