3.4. Identification of general issues and opportunities

It is advisable to identify social, economic, environmental, and governance issues and opportunities. In most cases, environmental, social and economic issues have a root cause that needs to be overcome, such as governance and institutional factors, lack of adequate knowledge, lack of training, inappropriate legislation, lack of enforcement, problems with user rights, and so on.

It is important that these root causes are investigated, and mitigation or remedial actions proposed. These are not factors that can always be overcome instantaneously and may require investment of time and financial resources.

External forcing factors should also be considered to include, for example, catastrophic events, climate change impacts, sudden changes in international markets, and the effects of other users of aquatic ecosystems on aquaculture such as agriculture and urban pollution of aquatic environments that may negatively affect aquaculture.

A large number of issues can be identified, but their importance varies greatly. Consequently, it is necessary to have some way of prioritizing them so that those that require immediate management decisions receive more attention within a plan of action. Examples and more details of issue identification and priorization can be found in FAO (2010), FAO (2003) and APFIC (2009).

The identification of issues also represents an opportunity for the implementation of a spatial planning process under an ecosystem approach to aquaculture, which ensures coordinated, orderly development and promotes sustainability. As an example, if one of the issues is fish disease and the lack of effective biosecurity (e.g. when farms are too close to each other leading to quick infection and reinfection), there is an opportunity to minimize fish disease risks and better respond to outbreaks through good spatial planning.

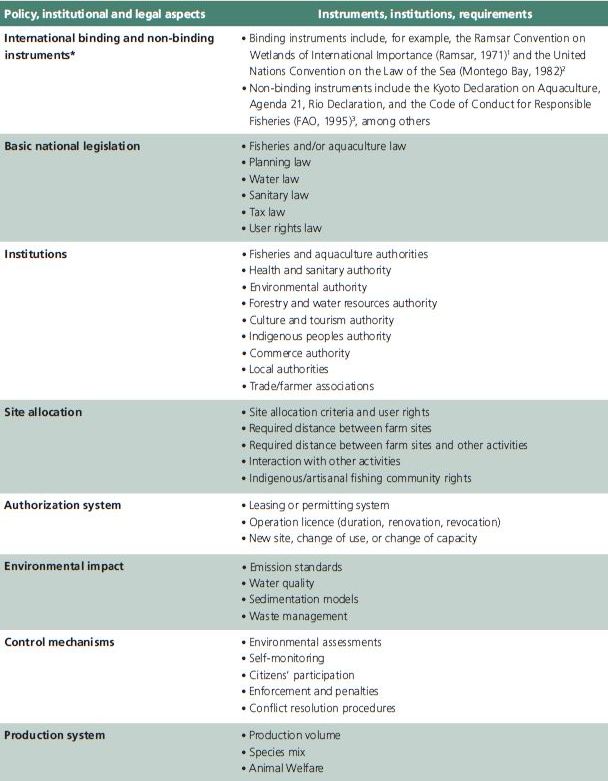

TABLE 5. Policy, institutional and legal aspects involved in sustainable aquaculture planning and management

*For more details on binding and non-binding agreements, see Annex 1.

1 United Nations. 1976. Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat. United Nations Treaty Series, Vol. 996, I-I- 1583. Entered into force 21 December 1975. (also available at https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%20996/volume-996-I-14583-English.pdf).

2 United Nations. 1994. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. 10 December 1982, Montego Bay, Jamaica. United Nations Treaty Series, Vol. 1833, 1-31363. Entered into force 16 November 1994. (also available at https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%201833/volume-1833-A-31363-English.pdf).

3 FAO. 1995. Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. Rome, FAO. 41 pp. (also available at www.fao.org/docrep/005/v9878e/v9878e00.htm).

Note:

Brugère et al.(2010) provide practical guidance on policy formulation and processes. It starts by reviewing governance concepts and international policy agendas relevant to aquaculture development and proceeds by defining “policy”, “strategy” and “plan” while explaining common planning terminology. See Brugère, C., Ridler, N., Haylor, G., Macfadyen, G. & Hishamunda, N. 2010. Aquaculture planning: policy formulation and implementation for sustainable development. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper. No. 542. Rome, FAO. 70 pp. (also available at www.fao.org/docrep/012/ i1601e/i1601e00.pdf).