6.2. Establishing an area management entity involving

local communities as appropriate In any specific farm, it is imperative that the farmer operates to the highest standards in managing the site. It may not, however, be possible to influence everything that happens in the wider area, especially when other farms are in operation. Added to this, the impacts of disease and environmental loading to a waterbody or watershed are the result of all farms operating in that waterbody or watershed; and control cannot be managed by any single farm working alone, and collective activity becomes important in these circumstances.

Where possible, all operating farms within an AMA should be members of a farmers’ or producers’ association as a means to allow representation in an area management entity, and which can set and enforce among members the norms of responsible behaviour, including, for example, the development of codes of conduct.

There is more than one way to develop an entity for an AMA, given that the legal, regulatory and institutional framework will vary at the national, regional and local levels. While the main impetus for the establishment of a farmers’ or producers’ association must come from the farmers themselves, there is nonetheless a significant role for the government as a convening body and, ultimately, the government has specific responsibility as the regulator and can place a high degree of impetus on the farmers to coordinate.

The government could help by providing basic services (e.g. veterinary, environmental impact monitoring, conflict resolution) through the farmers’ association, which will encourage cooperation by all farmers.

Importantly, the government may also need to create a formal structure through which it engages with the farmers’ associations that develop.

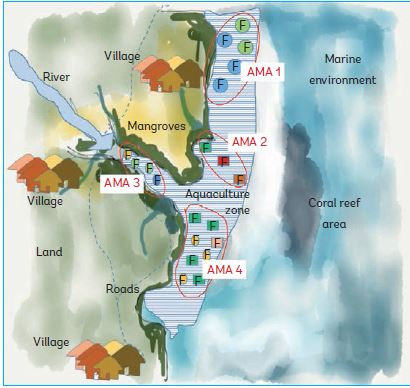

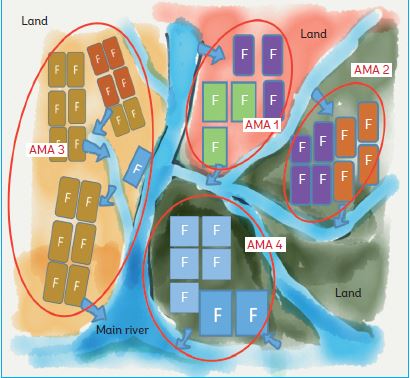

FIGURE 5a and 5b. Conceptual arrangement of aquaculture farming sites clustered within management areas designated within aquaculture zones

a. Coastal and marine aquaculture

Note:

Schematic figure of a designated aquaculture zone (hatched area in blue colour) representing an estuary and the adjacent coastal marine area.

Individual farms/sites (F), owned by different farmers, are presented in different colours and can incorporate different species and farming systems.

Four clusters of farms illustrate examples of AMAs, grouped according to a set of criteria that include risks and opportunities and that account for tides and water movement.

b. Inland aquaculture

Note:

Schematic figure of an existing aquaculture zone (the whole depicted area) representing individual land-based farms (F), e.g. catfish ponds and/or

other species, that may be owned by different farmers (presented in different colours). In this example, there are four AMAs. The commonality in the

AMA is the water sources and water flow (arrows) as the priority criteria (e.g. addressing fish health and environmental risks) used to set boundaries

of the AMAs.

The number of individual farmers to be included in an AMA should be carefully planned and discussed to make the AMA operational. Some good examples of farmer associations include those in Chile, Hainan Island (China), India and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

In Chile, there are approximately 17 corporate entities in the main producer’s association, Salmon Chile, and when a significant disease outbreak occurred, aquaculture area management was used to overcome and manage the outbreak, with Salmon Chile developing and implementing some of the response measures.

The Scottish Salmon Producers Organisation (SSPO) incorporates 10 commercial decision-making entities, all of whom adhere to common principles of behaviour, adopt best practices, and share important disease and market information for the benefit of all members. In Scotland, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, AMAs were also developed out of a need to contain a disease outbreak, infectious salmon anemia (ISA), and which included control measures to eliminate transfer of stock between AMAs.

The Sustainable Fisheries Partnership (SFP) organizes farmers’ associations into groups of approximately 20 on Hainan Island (China) and continues to support the Hainan Tilapia Sustainability Alliance. It is driven by a group of leading local companies who support the associations with seed, feed, technical support, farming and processing, and increasingly involving more of the local industry.

Cluster management, used to implement appropriate better management practices in Andhra Pradesh, India, can be an effective tool for improving aquaculture governance and management in the small-scale farming sector, enabling farmers to work together, improve production, develop sufficient economies of scale and knowledge to participate in modern market chains, increase their ability to join certification schemes, improve their reliability of production, and reduce risks such as disease (Kassam, Subasinghe and Phillips, 2011).

The structure of the AMA entity will vary depending on whether parties are the same size. AMA entities should be inclusive, as appropriate, for identification of issues, and stakeholder participation is essential.

Under these circumstances, undue dominance by To be effective, it is important that all or nearly all of the farmers are part of the management plan, so as to avoid cheating on best practices that can lead to disaster for all. The SSPO in Scotland, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and Salmon Chile in Chile represent ~90 percent of production in their respective management areas, and have been successful in coordinating and expanding production.

Where there is already a well-established aquaculture industry, it may be practically difficult to reorganize farms into defined aquaculture areas, in which case it may be necessary to adopt a strategic approach that establishes a working area management entity around a core of interested farmers, and gradually expanding to incorporate as many other farmers in the watershed as possible. If a serious problem occurs, such as a disease outbreak or pollution problems that affect an aquaculture area, and a sizeable number of farmers refuse to cooperate with the area management entity, it may be necessary for the government to impose regulations that require participation in an AMA as part of the permitting/leasing process to force the process.

The different scales of farmer groups will have a different internal governance and management system. Any system developed must formally identify how decisions will be made, have clear leadership and hierarchy within the group, and determine how the costs and any profits will be managed. In small farmer groups, it is easy for all members to be involved in day-to-day decision-making, but as farmer groups become larger, representatives are usually chosen to manage the group on behalf of members. In some cases, group members may not have sufficient business and management skills and experience to manage the AMA effectively and could employ professional managers from outside the group to manage their organization until sufficient experience is gained. Management of larger, more complex AMAs can be a time-consuming task, leaving little time for people to focus on their own individual farm management and production, and is another reason why a professional manager may be useful.

one or more larger commercial entities within an AMA can lead to disagreement on a course of action (e.g. affordable by some but not all), which might place a burden on the larger companies in providing the needed financial and other support to smaller farmers within the AMA. Conversely, there are instances where larger companies that support small farmers facilitate overall development and support to small farmers who have less capacity to take action. Some AMAs will make more sense for large-scale commercial aquaculture, while other AMAs could include a mix of producer sizes and types or could be designed just for small-scale farmers.

6.2.1 What does the area management entity do?

The purpose of the area management entity is the setting and implementation of general management goals and objectives for the AMA, developing common practices that ensure commonality in operations to the best and highest standards possible, and focusing on the activity that cannot be achieved by each farmer alone. In doing so, the entity is able to develop a management plan for the AMA.

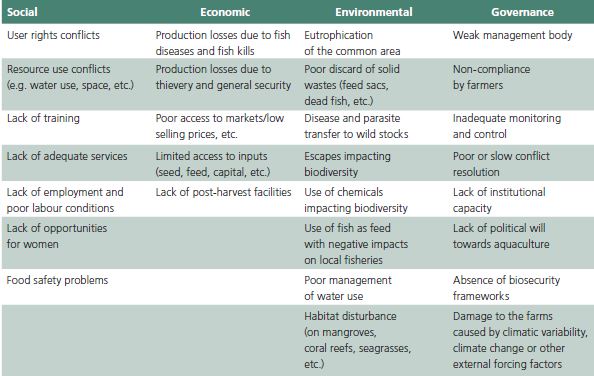

A range of issues that could be best addressed at the level of the farmer’s association are listed in Table 11. What is important is that the activity is of direct relevance and benefit to farmers, and that it leads to effective management of the AMA. The entity is not there specifically to resolve individual disputes between farmers, although the management entity can of course play a conciliation role where this does occur.

A major justification for collective action on the part of fish farmers is the reduction of risk to the farming system and to natural and social systems.

To guide the creation of an area management plan, a thorough risk assessment should be considered to prioritize the most important risks that should be addressed, and identify actions to be implemented to overcome or otherwise mitigate the risks.

The majority of relevant threats “from and to” aquaculture have a spatial dimension and can be mapped. Risk mapping of AMAs should include those risks associated with the clustering of a number of farms within the same water resource, as well as external impacts that can affect the farm cluster, for example:

• eutrophication or low dissolved oxygen levels;

• impact on sensitive habitats;

• impact on sensitive flora (e.g. posidonia beds) or fauna;

• predators (e.g. diving birds, otters, seals);

• epizootics/fish disease outbreaks (e.g. ISA);

• social impact and conflict with local communities and other users of the resource, including, for example, theft;

• storms and storm surge;

• flooding; and

• algal blooms.

A variety of data and tools exist to support risk mapping analysis. Some GIS-capable systems are specifically targeted at risk mapping, and many general-use GIS systems have sufficient capability to be incorporated into risk management strategies.

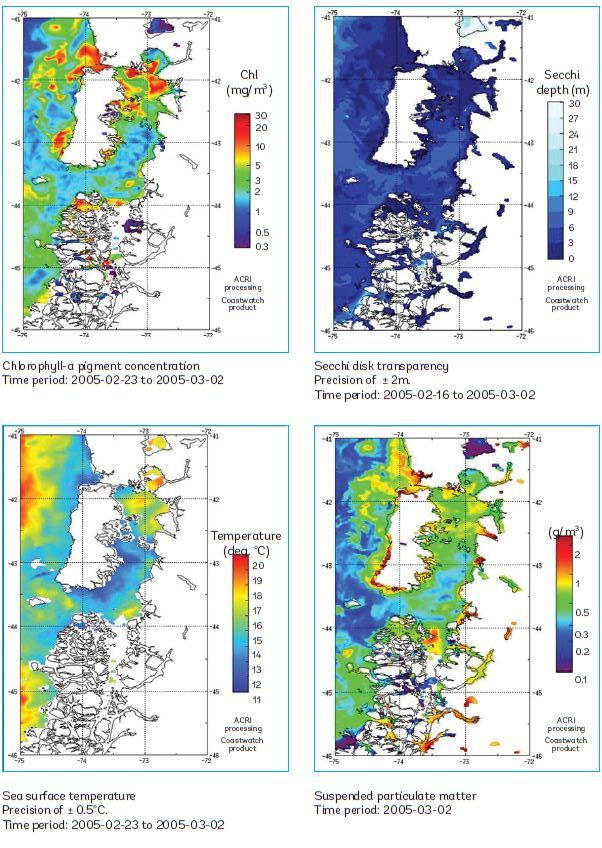

Remote sensing is a useful tool for the capture of data subsequently to be incorporated into a GIS, and for real-time monitoring of environmental conditions for operational management of aquaculture facilities. Satellite imagery has an important role to play in the early detection of harmful algal blooms (HABs). For example, in Chile, an early warning service based on Earth observation data delivers forecasts of potential HABs to aquaculture companies via a customized Internet portal (Figure 6). This Chilean case was led by Hatfield Consultants Ltd (Hatfield, UK), using funding from the European Space Agency-funded Chilean Aquaculture Project.

FIGURE 6. Monitoring and modelling of bloom events in the Gulf of Ancud and Corcovado, south of Puerto Montt in Chile

Notes:

• Data extracted from Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (or MODIS), presented in a composite image showing data over a period of 15 days. Data distributed daily to the end users.

• MODIS is a key instrument aboard the Terra and Aqua satellites. Terra MODIS and Aqua MODIS are viewing the entire Earth’s surface every 1 to 2 days. These data improve our understanding of global dynamics and processes occurring on the land, in the oceans, and in the lower atmosphere.

Source: Stockwell et al. (2006).

Another example of early warning for aquaculture is in Europe: the project Applied Simulations and Integrated Modelling for the Understanding of Toxic and Harmful Algal Blooms (ASIMUTH) funded by the European Union (www.asimuth.eu) used a collection of satellite and modelling data to construct a HAB forecasting tool. They incorporated ocean, geophysical, biological and toxicity data to build a near-real-time warning system, which took the form of a Web portal, an SMS alert system for farmers, and a smartphone app. The Web portal is curated and maintained by scientists in each country participating in ASIMUTH (France, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom of reat Britain and Northern Ireland).

Over and above the issues listed in Table 11 are the key management measures that have been taken to address the key issues listed above where collective action is better than singular action, namely:

Improving aquatic animal health management and biosecurity

• Develop a common aquatic animal health and biosecurity plan for the area. Defines the approach to mitigate against disease risks for the area.

• Implementation of single year classes of stock (e.g. fish) where juvenile inputs are coordinated and managed in order to ensure there is no disease transfer through mixing stocks and to allow for a fallow period to break disease cycles.

• Disease control through regular disease surveillance and synchronized disease and parasite treatments.

Treatment with the same medication is useful, and use of only authorized medication is expected.

• Vaccination of stock for specific diseases, where vaccines are available, with vaccination of all juveniles prior to stocking.

TABLE 11. Common issues to be addressed in aquaculture management areas

• Coordination for fallowing and restocking dates.

Synchronized fallowing, leaving the whole area empty of cultured fish for a specified time, and subsequent coordinated restocking supports biosecurity. Dates should be agreed upon between all parties and should be obligatory.

• Monitor the health status of newly stocked juveniles.

There should be agreement on the quality of the juveniles to be stocked into a management area, which may include: physiological status of juveniles; use of vaccines; sourcing juveniles from specific pathogen free sources; and tests for specific pathogens on arrival.

• Control of movement of gametes/eggs/stock between the farms within the AMA and into the AMA from external sources.

• Disinfection of equipment, well boats, and so on at farms, and following any movements between different farms by defining the expected disinfection protocols.

• Regular monitoring and reporting of aquatic animal health status, regular monitoring of disease criteria, and other management measures within the AMA.

This should include measures to be taken against non-conforming or non-complying farmers.

• Reconsidering the AMA boundaries to control a disease; for example, following the definition of epidemiological units in order to limit spread and impact of disease outbreaks within the common area.

For more information on biosecurity, see Annex 2.

Control of environmental impact, particularly cumulative impact

• Establishing the carrying capacity for the area to receive nutrients. In most cases, this is one of the first measures needed to adjust production and plan for the future of the AMA.

• Protecting natural genetic resources. Preparation of containment and contingency plans to minimize escapes and to control the input of alien (nonnative) species introduction.

• Improving water quality by reducing contribution to eutrophication. This will involve an improvement in FCR so that excess nutrient wastes are also reduced.

May involve re-siting farming structures (e.g. in the case of cages) where a new layout for the AMA could improve nutrient flows. This is also related to the first bullet point above.

• Environmental monitoring and implementation of regular environmental monitoring surveys and reporting and sharing of results.

• Fallowing of aquaculture areas. Synchronized fallowing of aquaculture areas, which leaves the whole area empty of cultured fish for a specified time. This is a biosecurity as well as an environmental management measure. It helps to break the disease and parasite cycle and allows the sediments and water quality to partially recover.

Improved economic performance of member farms

• Negotiation of supply and service contracts, whereby effective economies of scale and better terms can be achieved by negotiating contracts for common services (such as environmental monitoring), as well as for technology, fertilizer and feed supplies, among others.

• Marketing. Sharing post-harvest facilities (ice machines, packing facilities, refrigeration facilities, etc.). Establishing a common marketing platform.

• Sharing of infrastructure, such as jetties, boat ramps, feed storage facilities, sorting, grading and marketing areas, and ice production plants.

• Sharing of services, such as net-making, net-washing and net-repair facilities.

• Data collection, reporting, analysis and information exchange. Information exchange may include:

veterinary reports; mortality rates; timing and types of medicines used; and mutual inspections for assurance purposes, both within the AMA entity and with external stakeholders, such as government departments.

• Coordinated harvesting and marketing that allows farms within the AMA to have a larger and continuous sales and marketing platform from which to sell products.

Social management measures and minimizing conflict with other resource users

• Facilitating and strengthening clusters and farmer associations.

• Identifying relevant social issues generated by aquaculture in the coastal communities.

• Social impact monitoring by agreeing on and setting indicators of impacts and regular monitoring of the impacts on local communities and other users of the water and other resources.

• Management of labour by monitoring workers’ health and that of their families, implementing safety standards, providing appropriate wages and benefits, and identifying additional employment opportunities along the value chain. This will also include developing and implementing training activities to upgrade the skills of workers.

• Implement conflict resolution and measures to avoid conflict. If conflict does occur between farmers and between the management area and local interests (with fishers, for example), then resolution procedures should be fair, uncomplicated and inexpensive.

Once key issues are identified and agreed upon by the group, the management entity should develop management measures to address the key issues. These will then be incorporated into an area management agreement or plan that can guide future action for implementation.6 The measures should be the most cost-effective set of management arrangements designed to generate acceptable performance in pursuit of the objectives.

Without a clear set of objectives and time frame for their achievement, the area management entity can turn into a “talk shop” and lose credibility among farmers, reducing its effectiveness and influence.

Some elements of an area management agreement or plan that should be considered are as follows:

• agreement on the participants;

• clear statements on the objectives and expected outcomes;

• definition of the area and the farms included;

• agreement on the management measures;

• a management structure must have a mechanism to engage with public agencies and organizations, representatives from stakeholders, NGOs and other sectors that use the aquatic resource;

• responsibilities for implementation of the management plan must be clearly allocated to particular institutions and individuals;

• all farmers within the AMA must agree to conform to the management plan;

• the management structure must be able, willing, and allowed to implement or administer the incentives and disincentives to farmers who do not conform to the management plan;

• an agreed upon timetable;

• the roles and responsibilities and desired competencies for the key persons participating in key management positions within the zone; and

• financial arrangements supporting the management plan and area management entity.