Introduction

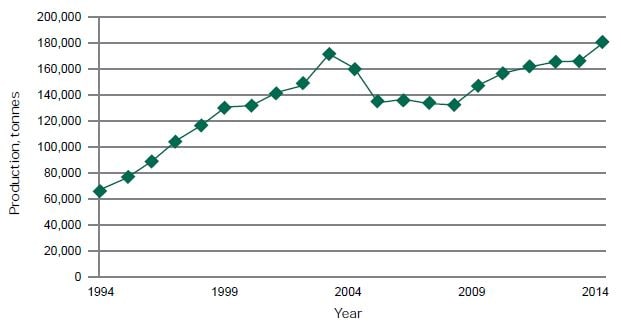

Scottish marine aquaculture is dominated by salmon, which at 179,000 tonnes2 production (Figure 1) is the world’s third largest and is Scotland’s largest single food export. Salmon producers share marine waters

Figure 1. Annual Scottish salmon production 1990–2014.

with a smaller production of marine farmed trout and other fish species such as halibut, together with shellfish production which is mostly of mussels and oysters.

Scottish aquaculture is strategically managed using area management principles in order to protect both production and the environment. Area management is used to control the spread of diseases and to ensure aquaculture production is in unpolluted waters, while at the same time ensuring waste products such as excess nutrients and organic wastes do not pollute the environment, keeping production levels within carrying capacity of the relevant water body. Landscape and conservation issues can also influence the siting of aquaculture out of sensitive zones.

The basic legal framework developed with the 1937 Disease of Fish Act (UK legislation) which established concepts of notifiable diseases and official movement controls to prevent the spread of infection in aquatic environments. With the establishment of marine salmon aquaculture in the 1970s the interactions of local groups of farms (Figure 2) with hydrodynamic movement required the development of local cooperation in the management of furunculosis and sea lice. From these local informal agreements, farm management areas were developed by industry and are enshrined in a Code of Good Practice for Finfish Aquaculture. This code is maintained and developed by a management group that consists of representatives from a range of major aquaculture producers and producers organisations (including government observers). In parallel, government and industry developed a system of official Disease Management Areas in the wake of a devastating outbreak of the notifiable disease, Infectious Salmon Anaemia (ISA).

In addition since the late 1990s, inshore water bodies with restricted tidal exchange (sea lochs, sounds, coastal embayments) have been used to manage nutrient and organic discharges and so limit allowable biomass at a water body level to stay within capacity to assimilate such wastes.

Scottish aquaculture’s area management is underpinned by considerable investment in Science, both directly through Marine Scotland Science and Scottish Universities, which include specialist centres such as the Scottish Association for Marine Science (University of the Highlands and Islands) and The Institute of Aquaculture (Stirling University). Research also occurs with collaboration at the UK, EU and global levels, for example the recently funded AQUASPACE project.

Figure 2. Example of a farm with 4 neighbours from southeast Shetland’s DMA 3a (Photo Sonia Duguid). During an ISA outbreak 4 of the 5 farms were infected, but infection did not spread outside the DMA.

Owing to the evolutionary process of establishing area management, Scotland has a range of differently defined, but in practice often very similar, areas over which aquaculture is managed. These have proved essential for managing epidemic Infectious Salmon Anaemia (Scotland is currently the only country to have successfully eradicated this disease) and in day-to-day management of fish health (particularly management of sea lice) while reducing conflict with other users of the coastal marine environment as a component part of Scotland’s National Marine Plan.3

3 www.gov.scot/Publications/2015/03/6517