4 Workshop presentations and conclusions

4.1 Zoning, Siting and Area Management under the EAA

An ecosystem approach to aquaculture (EAA)1

1 FAO. 2010. Aquaculture development. 4. Ecosystem approach to aquaculture. FAO Technical Guidelines for Responsible Fisheries. No. 5, Suppl. 4. Rome, FAO. 53 pp. (also available at www.fao.org/ docrep/013/i1750e/i1750e00.htm).

is a “strategy for the integration of the activity within the wider ecosystem such that it promotes sustainable development, equity and resilience of interlinked social-ecological systems.” The EAA provides a planning and management framework by which parts of the aquaculture sector can be effectively integrated into local planning and affords clear mechanisms for engaging with producers, government and other users of coastal resources. This leads to the effective management of aquaculture operations by taking into account the environmental, socioeconomic and governance aspects and explicitly including concepts of carrying capacity and risk.

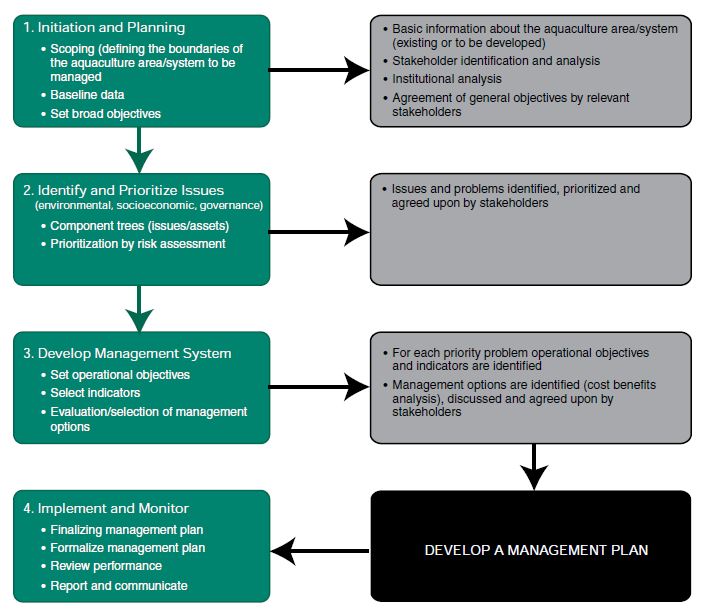

The EAA normally starts with a scoping and definition of the boundaries of the system to be managed, followed by the identification of issues and some risk assessment to prioritize those that require more immediate management. Operational objectives are then agreed upon and management plans developed to address the more relevant issues. A monitoring and evaluation system is embedded to periodically assess the level of implementation and the ability to address the selected issues. The Figure illustrates the process of EAA and steps in the process.

EAA can be implemented at any scale to address the development or to address aquaculture issues at local level, be it a cluster of farms, a cooperative of farmers.

It can be applied to a water body such as a small aquaculture watershed, a lake, a coastal area, a province, or at the national level. Implementation can be best achieved in designed Aquaculture Management Areas (AMAs) or local management units. These can be aquaculture parks, aquaculture clusters or any aquaculture area where farms share a common water body or source that allows a common management system. The spatial planning of aquaculture is an essential tool in the implementation of EAA and in the design of AMAs (FAO, 20132; Ross et al., 2013).2,3

2 FAO. 2013. Applying spatial planning for promoting future aquaculture growth. Seventh Session of the Sub-Committee on Aquaculture of the FAO Committee on Fisheries. St Petersburg, Russian Federation, 7–11 October 2013. Discussion document: COFI:AQ/VII/2013/6. (also available at www.fao.org/cofi/43696051f ac6d003870636160688ecc69a6120.pdf).

3 Ross LG, Telfer TC, Falconer L, Soto D, Aguilar-Manjarrez J, eds. 2013. Site selection and carrying capacities for inland and coastal aquaculture. FAO/Institute of Aquaculture, University of Stirling, Expert Workshop, 6–8 December 2010. Stirling, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Proceedings No. 21. Rome, FAO. 46 pp. Includes a CD-ROM containing the full document (282 pp.). (also available at www.fao.org/docrep/017/i3099e/i3099e00.htm).

The EAA is best implemented under a national aquaculture policy or other relevant policies (e.g., food security). It requires adequate and fair regulations which permit the growth of a healthy aquaculture sector capable of competing in the local, national or world markets at the same time protecting the sector from threats such as disease, chemical contamination, overcapacity, displacement by other sectors and environmental harm. Often EAA implementation requires reviewing and improving current norms and regulations. The implementation of EAA management plans in the mentioned AMAs can significantly improve local adoption and implementation of national strategies. Such management plans use different approaches and tools such as strategic environmental assessment (SEIA) and risk assessment (RA). The plans require the application of better management practices and biosecurity protocols.

Aquaculture Zoning: Why This Is Needed and How to Go About It

Aquaculture zoning can be used to identify potential areas for aquaculture growth where aquaculture is new, and to help regulate the development of aquaculture where aquaculture is already well established.

In some countries, aquaculture farms have been organized into small management groups such as “clusters,” “aquaculture parks,” “regions” or “zones.”

These can increase social and economic benefits to small-scale producers by promoting collective action.

However, any clustering initiative requires prudent observation in order not to exacerbate biosecurity (disease) and environmental capacity issues through over concentrated development.

Zoning can help address a number of issues such as integrated management, risk assessment, coastal aquaculture development, expansion of mariculture further offshore, aquatic animal health (biosecurity), better management practices, watersheds management, and aquaculture in the context of competing, conflicting and complementary uses of land and water.

Finding optimal solutions to these issues depends in part on finding a suitable zoning strategy supported by zoning policies. The zoning process is normally led by national and/or local governments with important stakeholder participation, equipped with relevant information and supported by relevant regulations.

Individual Site Selection

Site selection (or physical carrying capacity) is based on the suitability for development of a given activity, taking into account the physical factors of the environment and the farming system. In its simplest form, it determines the development potential of any location, but is not normally designed to evaluate that against regulations or limitations of any kind. In this context, this can also be considered as identification of sites or potential aquaculture zones from which a subsequent more specific site selection can be made for actual development.

Site selection is highly dependent on the type of aquaculture system, the location and interactions between the systems, and the surrounding environment.

However, decisions on site selection are usually made on an individual basis in response to applications for tenure; therefore this mechanism ignores the fact that many of the major concerns involve regional or cumulative impacts.

This process is normally led by private sector, local land owners, or villagers. Government assists with clear regulations for the process and requirements for site licensing.

Aquaculture Management Areas AMAs, Why They Are Needed and How to Approach This

Aquaculture Management Areas (AMA), can be aquaculture parks, aquaculture clusters or any aquaculture area where farms are sharing a common water body or source and may benefit from a common management system including minimizing environmental, social and fish health risks. AMAs can also be quite beneficial when clustering small farmers that can benefit from joint access to feed, seed technical support and access to markets and postharvest services.

The designation of an AMA relies on some form of spatial risk assessment where the understanding of physical factors such as water flow, currents and the system’s capacity to assimilate organic matter is at the core of biosecurity and environmental health.

Considerations of socioeconomic carrying capacity are also needed for example regarding provision of services to the farmers, access to markets and, very important, conflict resolution with other users of the common resources and to enhance the potential for integration with other sectors (e.g., with fisheries, agriculture, etc.).

In most countries where aquaculture is practiced, EIA is the most commonly applied environmental regulation but it applies mostly to large-scale intensive farming (cage farming, shrimp). Full EIA is not applied to the bulk of global aquaculture production because most production is small scale, and in many cases a traditional activity. However, it is important to recognize that many small-scale aquaculture activities could have significant impacts on the recipient water body and therefore some form of strategic environmental management is needed.

The need to develop management plans and biosecurity frameworks is even more obvious at the level of AMAs where the farms are closely sited and/or connected by the water flow; addressing disease risks needs to be done in a concerted way for the relevant spatial unit.

AMAs require a structure and management system that may include setting some limits to the maximum production per area, distance among farms, and stocking density. It includes monitoring (of environmental, fish health, socioeconomic aspects, etc.) and evaluation. EAA provides the steps and describes the process to develop management plans for AMAs that go beyond individual farms.

The establishment of AMAs could be a significant step towards the sustainable intensification of aquaculture, especially in regions such as Asia where the farms are already there (especially ponds) and therefore a step forward in environmental management and assurance of biosecurity.